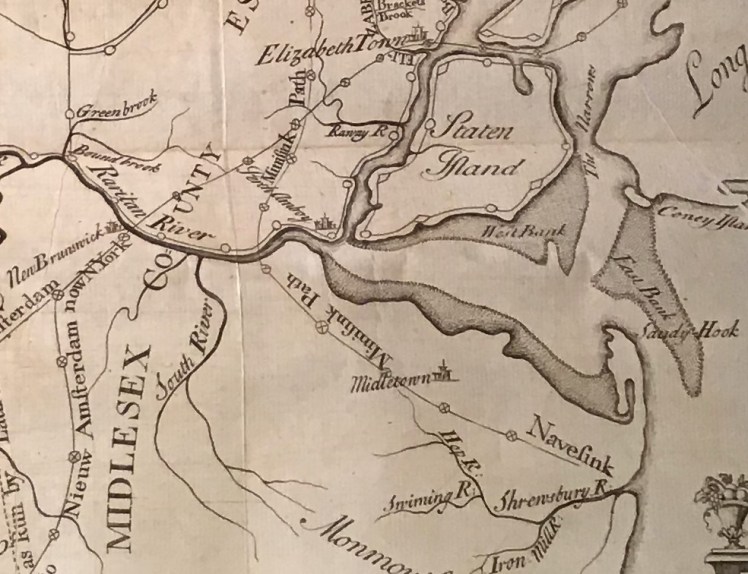

NEAR a bend in the Raritan River now crossed by hundreds of thousands of motorists every day, there was once little to disturb the routine movements of birds, beasts and tides except an occasional transit by raft or canoe. Here the river was met by what, in the imagination of William A. Whitehead, served as a “great thoroughfare,” formed over the centuries by the footfalls of New Jersey’s earliest inhabitants.1

It’s unclear how conversant Whitehead, while a young resident of Perth Amboy, the former East Jersey capital, may have been with the colonial surveys and maps that so much occupied him in later life. But the Minisink Path, that regular route of native travel and trade between the Atlantic and the upper Delaware, must have come to his attention early on. Perhaps in his adolescent wanderings he even sought out traces of the crossing, “a little to the westward of Amboy.”2

By then, any remains of the Minisink Path would have been hard to find. A century and a half of trade, migration and war had all but erased the indigenous Lenape and their ways of life. The landscape they knew had been dramatically transformed. Yet Whitehead’s enthusiastic scrutiny and tireless dissemination of colonial-era records allowed him to show just how much had changed since the beginnings of white settlement.

The means whereby people, goods and information had moved within and across New Jersey engaged his curiosity, and were a theme to which he returned often in his writings. Those investigations prove New Jersey’s advances in travel, at least during its colonial period, to have been surprisingly slow and halting.

The first European settlements in the territory of New Jersey were clustered along the margins, and had limited communication with the interior or with each other. “Much of the province,” said Whitehead, “was yet an unexplored wilderness, or one which had been traversed only by the hunter of the wild game that abounded, or the no less hardy seeker after desirable tracts of land.”3 An early settler, compelled to take up farming “in the plains,” miles away from a navigable river, quite understood the uniqueness of his position: “we have the honour to be the first Inland planters in this part of America,” he wrote, “the which I would have grudged at, had I not found the goodness of the Land upwards will countervaill the trouble of transportation to the water.”4

Whitehead credited Dutch colonists with opening the earliest passable road to join East and West Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania, and the two cities that would grow into the largest in British America. This route, starting near Elizabethtown and running southwest, intersected the Minisink Path, crossed the Raritan “at low water” near the present site of New Brunswick (Inian’s Ferry), then continued in a straight line to the Falls of the Delaware, just above Trenton.5

Whitehead evidently failed to recognize that this road followed another Indian footpath, the Assanpink Trail. Its English nomenclature attested to the route’s later popularity: maps called it the Upper Road; a branch named the Lower Road departed from it south of the Raritan and came to the Delaware “by a more circuitous route,” arriving at the site of Burlington, the West Jersey capital. By Whitehead’s day the Upper Road had been “widened and improved,” and was known simply as the “old road.”6

Officials in the colonial government were slow to recognize the value of a unified transportation system, instructing each town to appoint commissioners to lay out its own “common highways.”7 The Proprietors of East Jersey, “ever solicitous for the growth of their Capital,” made “strenuous exertions” to draw traffic away from the old road, launching in 1684 a new land route from Perth Amboy to the Delaware, and a ferry connection from Amboy to New York. Despite these efforts, says Whitehead, “the old Dutch road continued to be preferred,” and in 1695 the provincial Assembly took it “under their care,” taxing innkeepers along the route for its maintenance.8

During New Jersey’s first turbulent years as a united province, the many charges against its divisive royal governor, Lord Cornbury, included that of using roads as a weapon against his political foes: “The layers out of the high way,” it was alleged, “pull’d down their Enemies Inclosures [and] laid waies through their Orchards, Gardens and Improvements.”9

Cornbury was also accused of giving one of his followers a 14-year monopoly carrying goods and passengers on the road between Perth Amboy and Burlington, a favor in violation of royal statute and “distructive to that freedom which Trade and Commerce Ought to have.”10 The governor responded that his grant was “so far from being a grievance or a monopoly, that by this means and no other a trade has been carried on between Philadelphia, Burlington, Amboy and New York, which was never known before: and in all probability, never would have been.”11

Advances in road regulation, and in the comfort and efficiency of travel across the province, were exceedingly slow to take hold. Commissioners, appointed in 1765 “for the purpose of shortening and straightening” several existing roads, failed to raise the necessary funds by a lottery set up for the purpose; such a shortfall “does not tell well for the public spirit then prevailing,” Whitehead observed. The last royal governor, William Franklin, complained that, of New Jersey’s main highways, “even those which lie between the two principal trading cities in North America, are seldom passable without danger or difficulty.”12

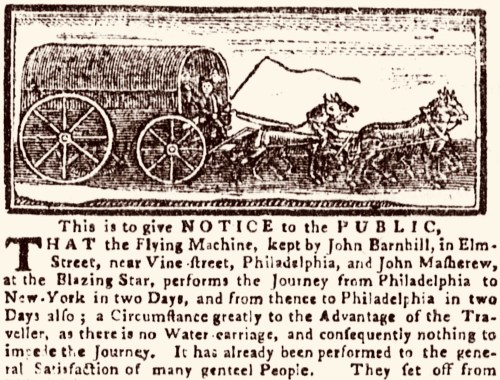

Eighteenth-century deficiencies in speed, comfort and safety must surely have depressed the demand for highway travel. Water routes remained crucial to linking the colony’s two halves, and the cities whose markets they relied on. The availability of “stage waggons,” promoted in 1733 as running weekly between the capitals of East and West Jersey, “or offt’er if that Business presents,” seems to have excited little, at first, in the way of patronage or rivalry. In 1750, Perth Amboy skipper Daniel O’Brien apprised anyone wishing “to transport either themselves, goods, wares, or merchandise from New York to Philadelphia” of a service combining “stage boat” and “stage wagon,” and boasted “that the passages are made in forty-eight hours less time than by any other line,” the entire journey taking from five to eight days.13

Two years later, O’Brien increased the frequency of his departures to twice weekly, and his success seems to have stimulated some competition. By the 1760s the New York and Philadelphia papers were carrying notices of “good stage wagons, and the seats set on springs,” making the trip in two days in summer, three in winter. “The wagons were modestly called ‘Flying Machines’,” noted Whitehead, “and the title soon became a favorite with all the stage proprietors.”14

Writing at the midpoint of the 1800s, Whitehead could not but marvel at the contrast between his own day, with the comfort and speed of movement brought on “by the progressive developments of the half century,” and that not too distant period “when all the travelling facilities in the State” could not have carried a tenth of the latter-day multitudes “who have so agreeably to themselves, with so little danger, and with so much regularity, ‘gone to and fro’ through the land.”15

From the tendency to intrigue and avarice implicit in provision of public service for private gain, at least one contemporary of Whitehead’s drew parallels between the colonial era and his own.16 This, however, Whitehead declined to do. To look past such harsh realities to the epoch’s “marvellous transformations,” to the revolutions they wrought “in the social condition, the business relations, and general improvement–morally and politically–of every community, however small, or however secluded,” may appear to modern sensibilities less than entirely honest.17 But I think Whitehead’s words here must be prescriptive rather than descriptive. He viewed these many forms of progress less as a feature, and more as an obligation of the age.

From the sluggish, sometimes faltering improvements in travel and trade across colonial New Jersey, Whitehead drew, as was his wont, a distinctly moral lesson. He allowed that some measure of “pride and self-congratulation” may be justified in “the advantages we possess over our ancestors”; yet previous generations, laboring under “restrictions … which to us seem almost to have been insurmountable,” had “materially advanced the welfare of the country and the happiness of their fellow men….” As he saw it, “to improve the favorable circumstances in which we are placed” is a social duty: it is expected that, freed from so many obstacles by those who have gone before, we will direct our “industry and enterprise … into other and more profitable channels.”18

Copyright © 2023-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

[1] William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary governments: a narrative of events connected with the settlement and progress of the province, until the surrender of the government to the Crown in 1702 [1703] (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1. Hereafter “Whitehead, East Jersey”) ([New York] 18461) 25, (Newark 18752) 28.

[2] Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 25, (18752) 28. With slightly less imprecision, he placed the Minisink Path’s meeting with the Raritan “about three miles above Perth Amboy.” William A. Whitehead, Contributions to the early history of Perth Amboy and adjoining country, with sketches of men and events in New Jersey during the provincial era (New York 1856, hereafter “Whitehead, Contributions”) 268. Later writers have placed the crossing at Kent’s (or Kents) Neck on the north bank of the river near Crab Island: Charles D. Deshler, “Early roads,” in W. Woodford Clayton, History of Union and Middlesex Counties, New Jersey, with biographical sketches of many of their pioneers and prominent men (Philadelphia 1882) 431; Reginald Pelham Bolton, Indian paths in the great metropolis (New York 1922) 204; Charles A. Philhower, “The Minisink Indian Trail,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society n.s. 8:3 (July 1923) (199-205) 202; id., “Indian days in Middlesex County, New Jersey,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society n.s. 12:4 (October 1927) (385-405) 389.

[3] G. P., “Glimpses of the past in New Jersey. No. XI.–Deputy Governor Rudyard,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 19 April 1842 2:1. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 94-95, (18752) 125.

[4] Thomas [Robert?] Fullertoun, “dated from his new possession, in the plains of new Cæsaria,” 7 January 1685, “to his Brother the Laird of Kinnaber,” in [George Scot,] The model of the government of the province of East-New-Jersey in America; and encouragements for such as designs to be concerned there. Published for information of such as are desirous to be interested in that place (Edinburgh 1685) 247-248, reprinted in Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 323, (18752) 463-464.

[5] G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia previous to the Revolution,” Newark daily advertiser 8 August 1840 2:1-2 (hereafter “G. P., ‘Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia’”); Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 160-161, (18752) 235; Whitehead, Contributions 268.

[6] While Whitehead referred to the Minisink as the sole Indian path in East Jersey “of which there is any record,” he conceded there were likely others. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 160, (18752) 235; Whitehead, Contributions 268. He was familiar with the designations “upper road” and “lower road” from A bill in the Chancery of New-Jersey, at the suit of John Earl of Stair, and others, Proprietors of the Eastern-Division of New-Jersey; against Benjamin Bond, and some other persons of Elizabeth-Town, distinguished by the name of the Clinker Lot Right Men … (New-York 1747, hereafter “Bill in Chancery”), Map no. II.

[7] Appointment in 1682 of boards of commissioners in the different counties led to “the first system of intercommunication”; however, “the roads when made were to be kept in order by the person, town, or township deriving the greatest benefit for them.” Legislation ordering speedy construction of a road between Middletown and Piscataway “upon the country charge,” and “under the penalty of what damage might ensue for the want thereof,” could be the exception that proved the rule, but from the thirty-day timeframe Whitehead deduced that it was “a work of little labor,” and even that the Minisink Path “may have facilitated the opening of this road through most of its length.” Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 161, (18752) 236; bound manuscript of East Jersey under the proprietary governments, Manuscript Group 177, William A. Whitehead Papers, New Jersey Historical Society.

[8] G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia”; Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 132, 161-162, (18752) 187, 236-237; Whitehead, Contributions 269 and cf. 279. Half a century later it was said that the old road via New Brunswick “still continues the principal and most frequented Road, notwithstanding many Endeavours to make it pass through Perth-Amboy.” Bill in Chancery 5.

[9] William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 3. Administrations of Lords Cornbury and Lovelace, and of Lieutenant Governor Ingoldesby. 1703-1709 (Archives of the State of New Jersey [hereafter “NJA”] ser. 1, 3. Newark 1881) 280-281; Eugene R. Sheridan, ed. The papers of Lewis Morris, 1: 1698-1730 (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 24. Newark 1991. Hereafter “Sheridan, Papers”) 75.

[10] Journal and votes of the House of Representatives of the province of Nova Cesarea, or New Jersey, in their first sessions of assembly, began at Perth Amboy, the 10th day of November, 1.703 (Jersey City 1872) 100, 105; Sheridan, Papers 53. Cornbury’s grant to Hugh Huddy of Burlington is printed in John Clement, “An old ferry and an old post road,” The Pennsylvania magazine of history and biography 9:4 (1885) 441-444.

[11] Whitehead quoted from Samuel Smith’s text of Cornbury’s reply in G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia,” and Whitehead, Contributions 270. Many years later he printed the reply in full in NJA ser. 1, 3:185-198 (page 187 contains the passage above). In earlier versions, the governor recalls a patent requested “by one Dellaman, who in colonel Hamilton’s time was permitted to drive a waggon for carrying goods, tho’ under no regulation, either with respect to times of going, or prices for carrying goods”: see Samuel Smith, The history of the colony of Nova-Cæsaria, or New-Jersey: containing, an account of its first settlement, progressive improvements, the original and present constitution, and other events, to the year 1721. With some particulars since; and a short view of its present state (Burlington, N.J. 1765) 302. When Whitehead printed the whole of Cornbury’s text, he silently corrected this passage to read “by one Dell (a man who …).” NJA ser. 1, 3:187.

[12] G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia”; Whitehead, Contributions 283 and n14. For the lottery, see William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. Extracts from American newspapers, relating to New Jersey, 5. 1762-1765 (NJA ser. 1, 24. Paterson, N.J. 1902) 589-591; 6. 1766-1767 (NJA ser. 1, 25. Paterson, N.J. 1903) 256-258. In answer to Franklin’s complaint, the Assembly stated that “straightening the Roads in many Places is impracticable from the unfitness of the Soil for Roads and the too great Damage it would be to many of the Inhabitants, obstacles that at Present we cannot conveniently remove….” See Frederick W. Ricord, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. Journal of the Governor and Council, 5. 1756-1768 (NJA ser. 1, 17. Trenton 1892) 466, 470.

[13] G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia”; Whitehead, Contributions 279-281. See also the 1751 advertisement for a “stage-boat” and “stage-waggon” combination, including O’Brien’s route between Perth Amboy and New York, reprinted in William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. Extracts from American newspapers, relating to New Jersey, 3. 1751-1755 (NJA ser. 1, 19. Paterson, N.J. 1897) 65-66.

[14] G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia”; cf. Whitehead, Contributions 282-283, and the advertisement for John Mercereau’s Flying Machine reprinted in William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. Extracts from American newspapers, relating to New Jersey, 9. 1772-1773 (NJA ser. 1, 28. Paterson, N.J. 1916) 23.

[15] “Travelling facilities,” Newark daily advertiser 8 April 1851 2:2 (hereafter “‘Travelling facilities’”). This unsigned column concludes by tabulating the last two years’ ridership between various points on the line of the New Jersey Railroad. Whitehead had been serving as the company’s secretary since November 1849. Combined with that detail, the sentiments in the article and its inclusion in a scrapbook made up chiefly of Whitehead’s “Contributions” make it all but certain that this was his work. See Scrapbook Collection, Manuscript Group 1494, SB 10, New Jersey Historical Society, page 96.

[16] Political economist Henry C. Carey, in a published challenge to the Joint Companies (the Delaware and Raritan Canal and Camden and Amboy Railroad) and their control of transportation through the state, compared modern citizens unfavorably with their colonial forbears who, “indisposed to be compelled to contribute to the building of palaces for their masters, … placed the matter before the Crown in such a light that the monopoly was abolished.” Letters to the people of New Jersey, on the frauds, extortions, and oppressions of the railroad monopoly, by a citizen of Burlington (Philadelphia 1848) 13. Carey’s was a dubious claim, for as Whitehead noted “none of the grievances suffered under Lord Cornbury’s administration were removed until his recall in 1710….” G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia”; Whitehead, Contributions 270.

[17] “Travelling facilities.”

[18] Bound manuscript of Contributions to the early history of Perth Amboy, Manuscript Group 177, William A. Whitehead Papers, New Jersey Historical Society; cf. “Travelling facilities” and Whitehead, Contributions 268. In G. P., “Traveling between N. York & Philadelphia,” Whitehead wrote even more plainly: “with so many more facilities than were possessed by our forefathers, how great should be our improvement in all things connected with the diffusion of knowledge and intelligence among the people!”