THE night sky gives us great cause for wonder: the more so, if we consider the vastness of the universe, an infinitesimal part of which is visible to our eyes. Those of us who scan the heavens for clues to the cosmos grapple with even deeper truths about space and time: by earthly measures, the stars in our sky could have been extinguished eons ago, for their light has traveled millions of miles and taken millions of years to reach us. What’s more, there are phenomena deep in space that science can’t explain, except by inferring the existence of matter that neither emits nor reflects light and so may never be seen.

The historian and biographer, whose eyes are seldom trained much above ground level, tend to have more confidence in the evidence of sight, and in their ability to comprehend it. They may readily admit to gaps and deficiencies in the sources, even to flaws in their own interpretations. But, without assurance that their knowledge has substance and their understanding is sound, they would have difficulty claiming for their work a classification other than fiction.

In approaching the history of New Jersey’s colonial era, William A. Whitehead knew how elusive the evidence and the explanations could be, how each passing year dimmed the light of knowledge with the risk of irremediable loss, “either by the destruction of paper memorials, or by taking from among us those few individuals … who still remain to enlighten us….” All eyewitnesses to the first century of colonization had, by his time, long since vanished; only documentary evidence was left, and it too was fast passing away.1

In his earliest writings, Whitehead characterized the founding era as one of “considerable obscurity,” “exceedingly confused,” a period dimly perceived and ill understood that only written records–many of them an ocean away–could somehow illuminate.2

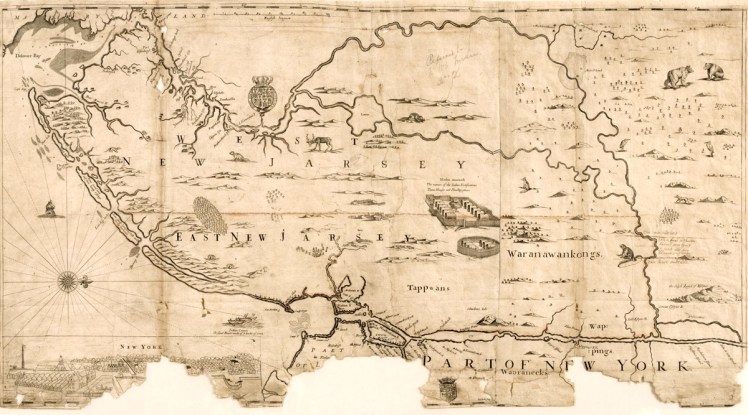

It didn’t help that, in the last third of the seventeenth century, New Jersey seemed to enjoy little peace. Clashes internal and external–between rulers and the ruled, purported owners and tillers of the soil, all parties inclined to dissolve into factions when not making war upon outsiders–ultimately led to a final surrender of the colony’s government to the English monarchy in 1702.

A quarter-century before, New Jersey had reverted to the English king after a fleeting renewal of rule by the Dutch. With the sale of half the proprietary in 1674 came a definitive separation between the governments of West and East Jersey. A struggle then began between the provinces of New Jersey and New York. This dispute, hinging on trade and the right to collect customs dues, threatened the very existence of the smaller colony as a separate jurisdiction.

In a dramatic turn, New York’s governor Edmund Andros pronounced the rule of Philip Carteret illegal, ordered the East Jersey governor arrested and had him tried as a usurper. Whitehead observed that through the whole ordeal “the spirit and firmness of Carteret quailed not,” but the brutal manner of his arrest and confinement left him disabled, and perhaps contributed to his death two years later.3

Whitehead was hard pressed to pinpoint any “known document or authority” to help penetrate the “considerable mystery” of New York’s outrage against its neighbor. News of the death of Sir George Carteret, Philip’s kinsman and one of the two original Lords Proprietors, may have further emboldened Andros. He also conceivably acted on secret instructions from the Duke of York–orders presumably destroyed once received. But within New Jersey, too, there were powers hostile to the incumbent’s authority, parties that would have tolerated and even welcomed the aggressions of the New York governor.4

As a consequence of Sir George’s death, the eastern province was sold at auction to a company of twelve associates, most of them London Quakers. These split their shares and sold half to another twelve. To Whitehead, the events of this period merited more than the “very cursory view” taken by his predecessors: the twenty-four proprietors represented “a strange mingling of professions, religions, and characters,” and, although only a handful ever came to America, he thought them well worth inquiring about.5

William Penn was destined to be the most famous of the twenty-four. While his interests were later centered on the eponymous province across the Delaware, Penn’s share in East Jersey remained undiminished during his lifetime. Non-Quaker Robert West was part of a plot to kill Charles II and his brother the Duke of York in 1683. The group included “gentlemen,” merchants, a baker, a mariner, and the Earl of Perth, in whose honor the East Jersey capital was named; he would later follow the Catholic king James II into exile, and die in France. Several were proprietors in Pennsylvania and West Jersey, simultaneously with their East Jersey interests. Of a few, whose stakes were but short-term investments, very little could be learned. Robert Barclay, a renowned Scots Quaker and apologist for his sect, was the proprietors’ choice for governor, causing the East Jersey venture to develop as a Scottish more than a Quaker enterprise.6

The desire for a re-annexation of New Jersey to the government of New York gained fresh impetus from the death of Charles II in 1685 and the succession of his brother as James II. Once on the throne, James set aside “as many as possible of the obligations and agreements to which, as Duke of York, he had acceded.”7 The proprietors “remonstrated–appealed to James’ sense of justice–made concessions–but all was of no avail”; it was decided to “abandon the hopeless contest” and formally surrender their patent, on the condition that the right to the soil be guaranteed them.8

Edmund Andros, the former governor of New York and now governor of the Dominion of New England, became the king’s willing servant, asserting control over his American domains. On James’s behalf, Andros assumed the government of every colony from Maine south to Delaware Bay, taking New York and New Jersey under his authority once more. But when his royal patron was deposed in 1688, Andros and the Dominion also fell from grace, and in their wake New Jersey was left with no colonial administration, proprietary or otherwise. Whitehead had to acknowledge that, for the next three years, “the history of East Jersey is almost a blank.”

Into this void stepped an illustrious historian, whose foremost critic–in the sparsely populated field of New Jersey history, at least–proved to be none other than William Whitehead. The second volume of George Bancroft’s serially published, best-selling and widely read History of the United States culminated in a tribute to “the peaceful inhabitants of New Jersey,” remarking how upon the defeat of Andros they were “left in a state of nature, their old governments were dissolved; and, in the simplicity and freedom of their wilderness, they were secure in their own innocence.”9

A reverence for “the established government of his country” practically compelled Whitehead to respond to this romantic depiction of a people finding liberty in the absence of government. While no meetings of the East Jersey governor and his council or of the assemblies were on record, the two provinces clearly “were not so entirely destitute of government as is supposed.” Inhabitants “were left to the guardianship of their county and town officers” whom Andros, “exhibiting greater wisdom than he generally manifested,” had allowed to remain in place. Their authority over local matters appeared “to have been respected and the peace of the community preserved.”10

Bancroft, in subsequent editions of his History, seemed to concede Whitehead’s point: “There is no reason to doubt,” he admitted, “that, in the several towns, officers were chosen, as before, by the inhabitants themselves, to regulate all local affairs….”11 But then, in Volume III, Bancroft apparently recanted, returning to the earlier view with a statement similar to his first, and “ushered in by a striking enquiry”:

Will you know with how little government a community of husbandmen may be safe? For twelve years, the whole province was not in a settled condition. From June, 1689, to August, 1692, East New Jersey had no government whatever, being, in time of war, without military officers, as well as without magistrates….12

Whitehead professed himself “somewhat startled” by the retraction. For so influential a writer to suggest that a community “may be safe” without government seemed to him irresponsible, particularly as the statement was incorporated into abridgments of Bancroft’s History “intended for the young….” That East Jersey, its population then numbering almost ten thousand, could have been “left in a state of nature” for three years, with “no courts–no administration of justice–no punishment of the guilty,” was a claim that demanded proof, “in more glaring colors than are now visible in the dim twilight which overshadows that period of our history.”

Bancroft’s opinion, however, didn’t originate with him. Earlier historians had come to the same conclusion, and its explanation seemed to lie in the quarrels that, after the return of proprietary rule in 1692, brought about its end a decade later.13

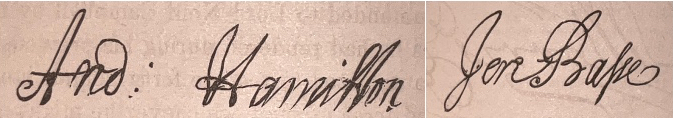

The popular Andrew Hamilton, appointed governor of both Jerseys, was able to reestablish the proprietors’ authority and, while “the seeds of dissension yet existed,” according to Whitehead peace generally prevailed.14 A concern for the welfare of the people seemed to guide the East and West Jersey assemblies during Hamilton’s first term, but this was abruptly cut short on the grounds that, as a native of Scotland, he was ineligible to hold office.

The new governor, Jeremiah Basse, enjoyed none of the good will that had rendered his predecessor’s tenure tranquil and more or less fruitful. Frustrated by persistent refusal to acknowledge his appointment, repeated defiance of his commands, and renewed encroachments by New York on New Jersey’s commercial independence, Basse returned to England having spent little more than a year in the colony.

Hamilton, restored to his former position, now found the province “torn with commotions within, and subject to aggressions from without….” The same parties that had contested Basse’s authority thwarted Hamilton’s efforts to restore order, out of what Whitehead termed a “deep rooted aversion” to any proprietary government, and a belief that its destruction would “advance their pecuniary interests.”15

After the validity even of Hamilton’s reappointment was questioned, the province descended further into anarchy:

tumultuous and seditious meetings were subsequently held, the justices appointed by him were assaulted, while sitting in open court, by bodies of armed men, the sheriffs were attacked and wounded when in the discharge of their duties, and every exertion made to seduce those peaceably disposed from their allegiance to the government: so that this period became known in after years as “the Revolution.”16

The change of government this “Revolution” produced, after long and difficult negotiations, brought New Jersey’s turbulent proprietary era to a close. Now a royal colony, the two Jerseys were united once and for all under a single head. The “malcontents … more desirous to subvert the authority of the proprietaries, than anxious as to the government that might succeed,” had got their wish, and an insinuation a half-century later, that New Jersey had enjoyed “more Liberty under the Proprietors than under the Crown,” would not go unnoticed in Whitehead’s analysis.17

By the patient and prolonged study of colonial records, Whitehead managed to compile a fair account of this troubled and convoluted history. His access to many documents was comparatively unlimited, but the picture, when not “almost a blank,” remained very fragmentary. Laborers, too, were few: “Were a spirit of examination into the history of New Jersey more prevalent,” he declared, “much of interest might yet be rescued from comparative oblivion….”18

Adding to the general neglect of the subject among his countrymen were the challenges of distance and loss. Forever optimistic that records yet to be discovered in English archives would cast a “clear light” on this already remote past, Whitehead pressed tirelessly for the funds needed to find and copy them.19

But the enterprise would have limited results for the early period, due especially to the near total disappearance, “much to be lamented,” of correspondence from the governors to the proprietors abroad.20 Although the contents of those dispatches and other records were forever fated to be cloaked in darkness, Whitehead drew from the remaining points of light a narrative that has largely stood the test of time.

Copyright © 2024-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

[1] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, on the early history of East Jersey. No. VIII,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 10 April 1840 2:3 (hereafter “G. P., ‘Grahame and Bancroft, No. VIII’”).

[2] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, on the early history of East Jersey. No. III,” Newark daily advertiser 23 March 1840 2:1-2 (hereafter “G. P., ‘Grahame and Bancroft, No. III’”); William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary governments: a narrative of events connected with the settlement and progress of the province, until the surrender of the government to the Crown in 1702 [1703] (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1. Hereafter “Whitehead, East Jersey”) ([New York] 18461) 63 n.86, (Newark 18752) 79 n.4.

[3] Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 73, (18752) 94 and n.1, 109-113; cf. Philip Carteret [1680] to “Mr. Coustrier,” in William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 1. 1631-1687 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 1. Newark 1880) 315-316.

[4] Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 70, 77, (18752) 90-91, 97-98.

[5] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. III”; Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 89, (18752) 118-119. George Bancroft’s misidentification of Thomas Rudyard as the twelve associates’ first provincial governor impelled Whitehead to castigate the senior scholar for evident lack of familiarity with Aaron Leaming and Jacob Spicer, The grants, concessions, and original constitutions of the province of New Jersey… (Philadelphia [1758]): “without either it or reference to the records, it is difficult to imagine how any one, claiming credit for research, could write even a sketch of the early history of N. Jersey.” G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, on the early history of East Jersey. No. IV,” Newark daily advertiser 27 March 1840 2:1-2; cf. George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the discovery of the American continent 2 (Boston 18371. Hereafter “Bancroft, History [18371] 2”) 411 and n.1; Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 91 n.7, (18752) 121 n.1. The charge was apparently just: only in a later edition did Bancroft cite Leaming and Spicer, in a copy procured for him by Garret D. Wall; there he corrected his error with reference to Whitehead’s articles, dating them mistakenly to 1839. George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the discovery of the American continent (Boston 184210. Hereafter Bancroft, History [184210]) 2:409 n.1, 412 n.1.

[6] Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 196-203, (18752) 170-181.

[7] Bancroft had excused James II’s conduct as the product of an impaired understanding: “He kept his word sacredly, unless it involved complicated relations, which he could scarcely comprehend.” Bancroft, History(18371) 2:407. To this Whitehead answered: “If so he must very frequently have found himself confused.” G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, on the early history of East Jersey. No. V,” Newark daily advertiser 31 March 1840 2:3-4 (hereafter “G. P., ‘Grahame and Bancroft, No. V’”); cf. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 110 and n.42, (18752) 144 and n.2.

[8] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. V”; cf. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 112-113, (18752) 159.

[9] Bancroft, History (18371) 2:451.

[10] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. V”; G. P., “Glimpses of the past in New Jersey. No. XX. Government of East Jersey from 1689 to 1692,” Newark daily advertiser 17 June 1842 2:3-4 (hereafter “G. P., ‘Glimpses of the past, No. XX’”); Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 113, 129-130, (18752) 160, 183-184.

[11] Bancroft, History (184210) 2:449.

[12] George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the discovery of the American continent (Boston 18416) 3:47.

[13] G. P., “Glimpses of the past, No. XX.” Cf. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 130 n.2, (18752) 184 n.1. Whitehead traced Bancroft’s misapprehension (one he believed James Grahame shared) to George Chalmers’s acceptance “as true” of a claim made in a 1699 anti-proprietary petition to the Crown: George Chalmers, Political annals of the present United Colonies, from their settlement to the Peace of 1763: compiled chiefly from records, and authorised often by the insertion of state-papers (London 1780) 622. The text of this petition was printed in William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 2. 1687-1703 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 2. Newark 1881. Hereafter “NJA, ser. 1, 2”) 322-327.

[14] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, on the early history of East Jersey. No. VI,” Newark daily advertiser 3 April 1840 2:1; cf. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 133-137, (18752) 188-193.

[15] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, on the early history of East Jersey. No. VII,” Newark daily advertiser 7 April 1840 2:1-2 (hereafter “G. P., ‘Grahame and Bancroft, No. VII’”); cf. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 148-151, (18752) 214-218.

[16] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. VII”; Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 150, (18752) 215; cf. NJA, ser. 1, 2:313-317, 327-340, 362-367. For the designation of this era’s disorders as “The Revolution,” see A bill in the Chancery of New-Jersey, at the suit of John Earl of Stair, and others, Proprietors of the Eastern-Division of New-Jersey; against Benjamin Bond, and some other persons of Elizabeth-Town, distinguished by the name of the Clinker Lot Right Men … (New-York 1747) 33, 45.

[17] W. A. Whitehead, “A review of some of the circumstances connected with the settlement of Elizabeth, N. J.,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society ser. 2, 1:4 (1869) (153-176) 170; Whitehead, East Jersey (18752) (267-285) 281.

[18] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. V.”

[19] This endeavor is explored at length in previous posts 049–Try, try again and 056–Our man in London.

[20] G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. III”; Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 114, 129, (18752) 149, 183. An exceptional survival, one of Andrew Hamilton’s dispatches that somehow found its way back to New Jersey and entered Whitehead’s collection, is cited in G. P., “Grahame and Bancroft, No. VII,” and printed in Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 223-227, (18752) 346-350. Letters from Gawen Lawrie and others, preserved through incorporation into George Scot’s The model of the government of the Province of East-New-Jersey in America (Edinburgh 1685), provided “some evidence,” said Whitehead, “that the value of the lost documents is not overrated.” East Jersey (18461) 114 n.50, (18752) 149 n.3.

One thought on “088–Dark matter”