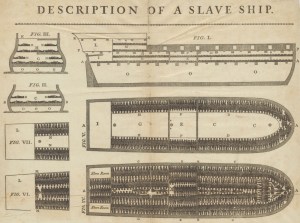

EFFORTS to comprehend their plight, at the moment when long-looming dread turned to unimaginable terror, leave one at a loss for words. Five hundred people, shackled for weeks in the lightless, airless hold of a ship, are startled by the boom of cannons above deck. They hear and feel the creak of straining timbers as the brig leans and lurches. With a sudden, awful crack, their prison ceases pitching, shivers and splits. Everyone and everything tips on its side. Bodies hang helplessly in their chains as the sea pours in, flooding the darkness.

The forty-one captive Africans crushed to death or drowned in their irons that horrible night represent a minuscule part of the untold millions whose lives were stolen over the centuries of the Atlantic slave trade. The trade to Cuba, the commerce in which these forty-one perished, had officially ended seven years earlier, but it went on clandestinely, and would only grow in the years to come. Yet, because the concerns of the moment were material ones, and the circumstances had no known precedent, the wreck of the brig Guerrero left a volume of documentation as remarkable as any maritime disaster of its day, and the anguished cries of its lost come nearer than any to reaching our ears.1

Spotted and chased by a Royal Navy man-of-war patrolling the Bahama Banks for slave ships, Guerrero tried in vain to escape as the British schooner closed in. After exchanges of fire and a pretense of surrender the brig, speeding full-sail away, ran aground on the Florida Reef, keeled over and lost its masts. Its pursuer also ran onto the reef and sat immobilized, a couple of miles away.

Sloops and schooners operating as wreckers managed to reach the two stranded vessels. Their crews worked through the day to rescue the more than 400 surviving Africans and 80 Spanish crew members from Guerrero. They lightened and floated the British schooner off the reef, and began to salvage what could be recovered of the slave ship’s boats, sails, rigging and furnishings.

In the process, however, two of the wreckers were commandeered by Spanish sailors and, with almost 300 Africans aboard, ran off to the barracoons and slave markets of Cuba. Left behind were the man-of-war, its British captain and crew, the ruined slaver, twelve Spanish crewmen, 121 African captives, and a single wrecker, the sloop Surprize. After Surprize made for Key West with the captives aboard, two of its consorts, the sloop Capital and the schooner General Geddes, continued salvage on Guerrero.

In December 1827, when the Guerrero incident occurred, the legal requirement that property salvaged off the Florida coast be brought to an American port of entry was not yet three years old. Key West, the closest such harbor, was still without a court having maritime jurisdiction. Because settlement amounts were decided by a board of arbitration, under pressure of local economic interests they sometimes reached astronomical sums.2 The British captain, who claimed the Africans and the salvaged remnants of Guerrero as his prize, refused to submit to such a settlement and sailed out of Key West, leaving the captives unguarded and paying the wreckers nothing for their trouble.

Then a place of just a few hundred inhabitants, Key West suddenly found 120 enslaved Africans (one had died in transit) it had to provide for and somehow dispose of.3 The Key West naval station was no more, and an army post not yet established. Of the federal officials in charge–both civilians–William Pinkney the collector of customs was the first to notify the authorities in Washington. He was told to keep the captives alive and in custody as economically as he could, to make a list of them including their ages, if possible, and to await “final instructions.”4

Instructions were not forthcoming. President John Quincy Adams and his Cabinet grappled, for the first four months of 1828, not only with opposing claims to the Africans as prizes but with the many legal provisions having a bearing on the case: the revenue laws, the wrecking law, the rights of capture and of salvage, and the laws of three distinct nations pertaining to the slave trade. “I never knew a transaction entangled with so many controvertible questions,” Adams reflected in his diary.5

From Key West, meanwhile, Pinkney together with the U.S. Marshal and his deputy, after contending with repeated attempts to take the captives by bribery or force, ultimately transferred them to the port of St. Augustine in northeast Florida, where many were hired out to local planters. Almost two years would pass before the captives again took ship for Africa. The 91 who survived reached Liberia finally in March 1830, as free persons.

When William A. Whitehead in 1831 took over the job that had been William Pinkney’s, another disaster of the magnitude of the Guerrero was far from unthinkable. Illegal slave transports to Cuba continued, as did efforts of British and American naval forces to stop them. Key West, though, had seen one important innovation: Judge James Webb now presided over a district court equipped with admiralty jurisdiction, leaving less of a legal vacuum into which a slaver like Guerrero might stray.6 But Whitehead still shouldered responsibility for all the port’s entrances and clearances, including its steadily increasing trade with Cuba. He had to reckon not only with the illegal trade just offshore, but with kaleidoscopic changes in the legal frameworks of slavery and freedom closer to home.

Especially in his first year as collector, Whitehead wrote often to the Treasury for help in deciding complex issues. In April 1831, he inquired of the Department about the plan of a certain “citizen and resident of the United States,” an unnamed entrepreneur desiring to purchase slaves in the Bahamas, emancipate them “before the proper authority,” then bring them to work on Key West as indentured apprentices, “in consideration of the benefit they have received,” for a period of ten years. Viewed by the Treasury Secretary as “a palpable violation” of the law,7 this scheme had to be abandoned, and presumably the anonymous employer went about importing enslaved Blacks from South Carolina or another of the Southern states.8 But peonage such as he envisioned was destined to flourish in the Caribbean and on the mainland, even after emancipation.

Late in the spring of 1831, a captain and trader sailing regularly between Cuba and Key West brought word of a thwarted insurrection among the Africans of Havana. A balloon ascension honoring the birthday of the King of Spain was the agreed-upon signal for the uprising, but the plot was betrayed and the alleged rebels were swiftly jailed. Learning “that the Island of Cuba was quiet,” the Charleston Courier suspected the rumors coming from Key West were without foundation.9 But rebellion was in the air. Two historic insurrections erupted later in the year, both led by Black preachers: Nat Turner’s in the state of Virginia and Sam Sharp’s on the island of Jamaica.

Whereas the aftermath of Sharp’s revolt helped speed slavery’s end in the British Caribbean, the immediate effect of Turner’s was to harden the confines in which Blacks both free and unfree were forced to live. To reduce the threat of future insurrections, American states and territories legislated tighter controls on the movements of Blacks and, to combat the “moral pestilence” of abolitionist sentiment, imposed restrictions to keep free Black mariners from all contact with slaves in port cities.10

While many states had longstanding bans on the introduction of non-natives or non-citizens of color, Congress in 1803 had made an exception for registered seamen. Nonwhite seafarers could be found employed on the merchant vessels of many nations, as vital components of their crews. But Southern states began in the 1820s to restrict their entry, and the Territory of Florida followed suit.11 Even bearing so-called “protection papers” as proof that they were free, Black seamen could face arbitrary imprisonment and enslavement.

In a circular letter from the Treasury Secretary, ships’ captains and customs collectors were ordered to comply strictly with the Act of 1803. Whitehead had this directive published for several weeks in the newspaper at Key West.12 But after the 1831 revolts, the legal landscape appeared to change. A new Florida law mandated the arrest of any free person of color migrating into the Territory, with the costs of imprisoning and removing him borne by the captain of the vessel that brought him there. If a sailor returned to Florida, he would be arrested and sold at auction for a term of five years.13

With the slow dismantling of slavery in The Bahamas and the British Caribbean through the 1830s, more Black mariners were working on merchant ships, and finding themselves at risk of capture on U.S. shores.14 Indeed, a grand jury in 1834 fulminated against “the introduction of free negroes and mulattoes” into the Florida Keys, something it alleged was occurring “almost daily and with impunity, and in utter disregard of the laws.” It viewed the practice as “calculated to favor the detestable views and purposes of fanatics and abolitionists” who wished “to tamper with, and corrupt our slave population.”15

Judge Webb ruled that the territorial legislature had not meant for free Blacks to be arrested or expelled unless and until they tried to become residents. But at least one Bahamian working on an American wrecking vessel was seized in Whitehead’s jurisdiction and sold into slavery, over the objections of the British colonial administration. Whitehead’s part in the matter seems to have left no record.16

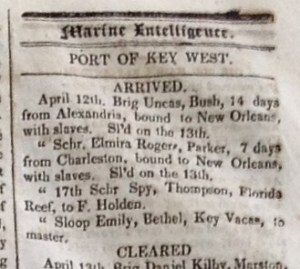

Much as the Guerrero disaster had done several years before, high-profile incidents like this monopolized the attention of the authorities. The everyday reality was more mundane and more insidious. As the illegal trade in captive Africans continued apace,17 so also did a legal traffic in human beings, carried from the exhausted Old South to the flourishing states further west, skirting the Keys and calling occasionally at Key West.

In the mid-1830s the hunger for unfree labor and the coastwise trade in slaves showed no signs of abating. Abolitionist voices became more strident, but no more successful.18 Whitehead saw the antislavery movement as having reached a crisis, soon to crumple before “the overwhelming force of public opinion.” In no small way he was right: out of the depths, the cries from Guerrero still struggle to be heard.19

Copyright © 2024-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

[1] For most details I defer to what continues to be the most thorough exploration in print of the disaster, its aftermath and legacy, Gail Swanson’s Slave ship Guerrero. The wrecking of a Spanish slaver off the coast of Key Largo, Florida with 561 Africans imprisoned in the hold while being pursued by the British warship HBM Nimble in 1827 (West Conshohocken, Pa. 2005).

[2] Owners of wrecking vessels sat on Key West’s wrecking “court,” and their propensity to enrich themselves by these judgments was notorious. “In some instances,” commented a Savannah paper, “fortunes have been realized by the salvage on a single vessel. A greater amount of salvage … is allowed at Key West than in any other part of the United States, or perhaps the world….” “Wrecking at Key West,” Savannah (Ga.) Georgian 7 January 1826 2:2. In a memorial to Congress, John W. Simonton appeared to concede that settlements were sometimes too high: “If, as is alleged to be the case, higher rates of allowance have been made, than was required by the risks and labor encountered in rescuing the property, it only proves the necessity of creating a tribunal clothed with Government sanction, that thereby such errors may for the future be prevented or avoided.” Charles Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIII. The territory of Florida 1824-1828 (Washington 1958; hereafter “Territorial papers XXIII”) (560-565) 562. See further J. W. Simonton, Washington 5 March 1828, to P. P. Barbour, in Territorial papers XXIII 1032-1034, and the documents there cited.

[3] Collector of customs William Pinkney sent the Treasury Department an enumeration of inhabitants made in February 1828. He counted 265 free whites permanently resident on the island (four-fifths of them male), 39 free Blacks and 17 slaves, for a total population of 321. He did not include in his census those saved from Guerrero, who were detained on Key West at the time. To the permanent residents Pinkney added 100 “free white Males employed 8 months in the year in the Fisheries.” Territorial papers XXIII 1055-1056.

[4] Richard Rush, Washington 7 February 1828, to Wm. Pinkney, copy (in Whitehead’s hand–see note 7 below) in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West, Dec. 13, 1826 to Mar. 29, 1833,” Correspondence of the Secretary of the Treasury with Collectors of Customs, 1789-1833. Record Group 56, General Records of the Department of the Treasury, National Archives and Records Administration, Microcopy No. 178, Roll 38 (Washington 1956; hereafter “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West”), page 26.

[5] The diaries of John Quincy Adams: a digital collection, Massachusetts Historical Society, 37:424 (entry of 6 February 1828). The first notice of the controversy in Adams’s diaries is an entry of 19 January 1828; already on 25 January he was able to say, “I have no doubt it will prove a troublesome affair.”

[6] Pleas for an admiralty court, including Pinkney’s in the context of the Guerrero case (W. Pinkney, Key West 23 December 1827, to Richard Rush, in Territorial papers XXIII 957), were finally heard, and Judge Webb was appointed to the new Southern Judicial District of Florida in June 1828; he arrived on Key West in October. After Whitehead’s brother John “verbally” informed President Andrew Jackson that the judge was absent for most of the year, leaving a marshal in charge, orders were given Webb to settle on the island or lose his commission. James Webb, Key West 27 October 1828, to Joseph M. White, in Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIV. The territory of Florida 1828-1834 (Washington 1959; hereafter Territorial papers XXIV) 112; Memorandum Book, in Daniel Feller et al., edd. The papers of Andrew Jackson, Volume VII, 1829 (Knoxville, Tenn. 2007) 261 (entry of 6 June 1829); Andrew Jackson, Washington 6 June 1829, to Martin Van Buren, in Miscellaneous letters of the Department of State, Microcopy No. 179, Roll 67 (Washington 1953), and in Territorial papers XXIV 228. Webb presided over admiralty and other cases until 1838 when he removed to the Republic of Texas, becoming Secretary of State there in 1839.

[7] The 20 April 1818 Act of Congress cited in Whitehead’s query and the reply to it reinforced the 1807 ban on the importation of slaves to the United States. 3 Stat. 450-453, and see 2 Stat. 426-430; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 16 April 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham, and S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 16 May 1831, to Wm. A. Whitehead, copies in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 105, 67. Transcribed by Whitehead from his own records, these letters replaced correspondence lost in the Treasury Department fire of 31 March 1833; Whitehead appears to have miscopied both the date of his own letter, writing 1833 for 1831, and the date of the law, which he gave as “April 2d.”

[8] Almost certainly the plan involved the Key West salt works; very possibly the unidentified “citizen” was entrepreneur and enslaver Richard Fitzpatrick, then Monroe County’s representative in the Territorial legislature. Reporting on a fact-finding mission to the Bahamas undertaken by “a gentleman interested in the soil of Key West,” the Key West Register foresaw great profits from salt production “if experienced Salt makers could be induced to leave the West Indies & reside here, (of which there can be no doubt,)….” In 1831, on a 25-year lease from the Whitehead family, Fitzpatrick took over a portion of the Key West salt pond and hired a free Afro-Bahamian, “a skilful and experienced Salt-maker,” to oversee the labor of some 30 enslaved men brought from Charleston. Key West (Fla.) register 12 February 1829 2:4; “Key West salt ponds,” Key West (Fla.) gazette 25 May 1831 2:4-3:1. Under the terms of Fitzpatrick’s lease, the Whiteheads retained a financial interest in his venture and reserved the right to become partners after three years: see my previous post 038-White gold.

[9] Key West gazette 8 June 1831 3:1; Charleston (S.C.) courier 16 June 1831 2:3.

[10] In a defense of South Carolina’s 1822 Negro Seamen’s Act and the detention of free Black sailors while their ships were in port, attorney Benjamin Faneuil Hunt was among the first to apply the phrases “moral contagion” and “moral pestilence” to the danger posed by free persons of color in South Carolina to “the peace of her citizens, and the security of her slave population,” indeed to the state’s very existence. See The argument of Benj. Faneuil Hunt, in the case of the arrest of the person claiming to be a British seaman, under the 3d section of the State Act of Dec. 1822, in relation to Negroes, &c. before the Hon. Judge Johnson, Circuit Judge of the United States, for 6th Circuit. Ex parte Henry Elkison, claiming to be a subject of His Britannic Majesty, vs. Francis G. Deliesseline, Sheriff of Charleston District (Charleston, S.C. 1823) 7; Michael A. Schoeppner, Moral contagion. Black Atlantic sailors, citizenship, and diplomacy in antebellum America (Cambridge University Press 2019) 41-47.

[11] Florida’s act “To prevent the future Migration of Free Negroes or Mulattoes to this Territory” exempted those “actually engaged under any contract of service on board of any ship or vessel … so long as … [they] shall remain in the actual employ, and on board said ship or vessel.” Acts of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida, passed at their 5th Session, 1826-7 (Tallahassee 1827) 81-84.

[12] S. D. Ingham, “Circular to Collectors of Customs,” 5 April 1831, printed in Key West gazette 13 (12?) October 1831 3:4 and repeated every week for five months. Whitehead also reprinted the 1803 text in “Notice,” The enquirer (Key West, Fla.) 2 May 1835 3:3-4 and in the following three issues.

[13] “An Act to prevent the future migration of Free Negroes or Mulattoes to this Territory, and for other purposes,” Acts of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida, passed at the 10th Session, commencing January 2d, and ending February 12th, 1832 (Tallahassee 1832) 143-145. A companion law was passed a week earlier: “An Act to provide for the collection of Judgments against free negroes and other persons, therein named,” ibid. 32-33. The latter act, which permitted enslavement of free persons of color for nonpayment of judgments and court fees, was “revived” in 1835: Acts of the Governor and Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida: passed at the Thirteenth Session, begun and held at the city of Tallahassee, on Monday Jan 5th, and ended Saturday Feb. 14th, 1835 (Tallahassee 1835) 315.

[14] Noting the prohibition on admittance of free Black mariners and the consequent seizure of one by the collector of a port in the Florida panhandle, the Enquirer, of which Whitehead was editor, expressed the hope “that no case has occurred or will occur to render it necessary to act upon it in this District.” The enquirer 2 May 1835 3:2. Later that year, the lieutenant governor of the Bahamas published Florida’s law to warn mariners “of the consequences of approaching a territory where they are liable to be thus dealt with.” This action provoked comment from Whitehead’s Enquirer: “The Legislative Council has thus deprived our wreckers of their most useful seamen.” W. M. G. Colebrooke, Nassau, N.P., 7 July 1835, to Charles Grant, Lord Glenelg, in British claims on the United States, vol. 4: Free Blacks, FO 5/579, U.K. National Archives (hereafter “British claims”) 45; “Government notice,” Royal gazette, and Bahama advertiser (Nassau, N.P.; hereafter “Royal gazette”) 8 July 1835 3:1-3; The enquirer 8 August 1835 3:1. In fact, the danger to free Black sailors coming into Key West had been foreseen at the dawn of the American presence there: see Royal gazette 1 May 1822 3:3.

[15] Key West (Fla.) enquirer 3 January 1835 2:2.

[16] William Delaney or Delancy, who shipped aboard a vessel at Nassau and was discharged at Key West, was jailed and on a writ of habeas corpus brought before Webb in April 1835. The judge determined that Florida’s law was not meant to prohibit employment of free persons of color as seamen, or to say that a vessel could not stop at Key West “to repair damages after a gale of wind, without incurring the liability of having the whole crew seized and sent to jail”; a sailor becoming a resident, however, and “being found within the reach of its process, can be made liable for that violation.” The enquirer 2 May 1835 3:2-3. William Forster, a freeborn British subject from Nassau, was arrested and expelled from Key West two years earlier, but shipping aboard the American schooner Amelia in Baltimore in 1835 he found himself once more at Key West. Although he never stepped foot on shore, Forster was taken forcibly from his vessel, charged under the 1832 law by Richard Fitzpatrick (now a justice of the peace at Key West), and sold into slavery for a term of five years. His captain, Henry Fitzgerald, purchased and liberated him after a few months. British claims 44-50.

[17] Writing at the end of his Key West sojourn, Whitehead commented on the persistence of illegal importations to Cuba: “The vigilance of the British cruisers” and a three-nation commission “having cognisance of such captures and impositions” had “materially diminished” the trade, but “still, as I have observed, the traffic continues.” G. P., “Letters from Havana. No. XIV,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 20 September 1838 2:1.

[18] The movement to “return” free Blacks to Africa did figure, at least briefly, in Key West history during Whitehead’s tenure. The brig Ajax, carrying emigrants from Kentucky and Tennessee to Liberia, set sail from New Orleans in April 1833, but was diverted to Key West after an outbreak of cholera. The brig and its passengers remained quarantined off Fleming’s Key, where 30 to 40 died. Nine citizens of Key West also perished of the disease. J. Winston Coleman, Jr., “The Kentucky Colonization Society,” The register of the Kentucky State Historical Society 39:126 (January 1941) (1-9) 3; cf. “Afflicting mortality,” Newark daily advertiser 17 June 1833 2:3.

[19] “From Mobile,” The enquirer 29 August 1835 3:3. Handwritten initials added to Whitehead’s copy identify this unsigned article as his own. Expeditions to locate traces of the wreck of Guerrero have had limited success, but continue to inspire; cf. David Kushner, “The hunt for the Atlantic’s most infamous slave shipwreck,” Esquire (online, 16 May 2023); Omnia Saed, “The Black divers excavating slave shipwrecks: ‘I’m telling my ancestors: I’m with you,’” The guardian (online, 3 September 2024). For the challenges inherent in identifying wrecked slavers see Jane Webster, “Slave ships and maritime archaeology: an overview,” International journal of historical archaeology 12:1 (March 2008) 6-19.