SUBLIME as her mysterious nickname, the Lady of the Green Mantle swept into Charleston harbor late in November 1830, there to replenish her supplies of fresh water, salt pork, cheese, hardtack, whiskey and other staples before departing on the next coastwise cruise.1 The crew on board Marion, as the swift vessel was officially called–a tribute to the wily general of the Revolution known as the Swamp Fox–were expecting to remain in port long enough to convey to Key West its new collector of the customs. But that mission would go unfulfilled. Owing to “some miscarriage in the mail,” by the time William A. Whitehead received his commission it was too late to make a connection, and Marion sailed without him.2

Whitehead booked passage instead on a crowded schooner that left Baltimore in mid-December and took an agonizing 38 days and nights to reach his destination.3 Eighteen more days would pass before Marion’s sleek silhouette rounded Whitehead Point and entered Key West harbor. With a cordial handclasp between the new collector and Captain John Jackson began a fresh chapter in the saga of a storied revenue cutter, its commanders and the ports they served.4

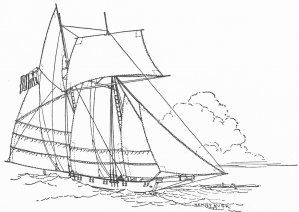

Five years earlier, Marion slid down the ways and into the waters of Baltimore harbor, the prototype of a new class of vessel built for speed and agility. A topsail schooner fielding a half dozen cannon, she had under Captain Jackson two lieutenants and a crew of about twenty, who plied a “cruising ground” the length of the Atlantic coast from North Carolina to the farthest of the Florida Keys.

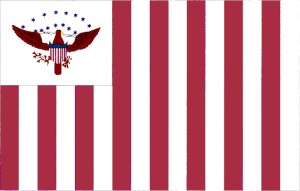

Placed under the superintendence of collectors of customs, revenue cutters like Marion were their eyes, ears and strong arms, protectors of the country’s fiscal well-being and enforcers of the wrecking laws. After 1831, they were ordered to render assistance to vessels in distress, making them forerunners of the Coast Guard. And on sprawling, sparsely settled shores like Florida’s, they chased pirates, kept widely scattered lighthouses supplied, and maintained a vital if sporadic link between collectors and the central government. Marion was assigned to carry northward the regular reports of the Key West collector, and to ensure that funds he took in were deposited in the Treasury’s account at Charleston.

The dynamics between collectors and captains of revenue cutters didn’t always run smoothly, especially as the latter were, for long periods, away from their immediate superiors on land. Indeed, the captains’ tendency to act independently and sometimes counter to orders exemplifies the truth that distance is not always the key to a happy marriage.

Relations between the first of Marion’s captains, Josiah Doane, and the collector at Key West, William Pinkney, were more antagonistic than not, leading the Secretary of the Treasury to urge on the pair “an harmonious cooperation between you, uninfluenced by any considerations or feelings other than those that look to the public service.”5 In their provisions for more than a hundred African captives, stranded at Key West by the wreck of a slave ship, some semblance of harmony could be found, but neither man relented in his attacks on the other. In 1828 Pinkney seized Marion and kept the cutter under guard until Doane was replaced.6

Soon after John Jackson took command of the cutter, Pinkney was succeeded as collector by Algernon Thruston. In 1829, Jackson and Thruston were embroiled in charges of election interference, when officials accused the captain of landing his crew in the Keys not once but twice to cast fraudulent votes. On one of those occasions, it was charged, the men “disguised themselves as common sailors” to fool the poll inspectors. While Jackson’s lieutenants may have been the architects of these deceptions, the inquiry that Thruston was ordered to conduct seems never to have occurred.7 The collector appears to have been remiss in other duties as well. Absent from Key West for long periods, he relinquished custom house affairs to a deputy who, in October 1830, was obliged to report the office “out of funds.”8

Stepping into Thruston’s vacancy the following January, William Whitehead found he urgently needed $3000 to pay Marion’s officers and crew, and $3000 more to compensate his remaining employees, buy oil for the lightship at Carysfort Reef, make sundry repairs and pay other expenses. Intending to draw on the Treasury account at Havana, Whitehead approached the commanders of Marion and another cutter in port to take his brother John to Cuba as his agent. Both declined to carry John Whitehead as “a passenger not in the service of the United States,” and although Jackson “after some delay” relented and executed his instructions, Whitehead felt compelled to submit the controversy to the Treasury secretary, who confirmed the collector’s authority over revenue cutters.9

Tellingly, on the very day that Whitehead was appointed, the Treasury sent instructions to Key West on how to proceed in cases of “disobedience of orders or other misconduct” on the part of revenue cutter officers.10 The Department must have anticipated still more conflicts between Marion’s commander and the new collector.

But changes were being contemplated at Washington that would end the governance Whitehead shared with his counterpart at Charleston. Effective the 1st of April, Charleston’s collector would have exclusive responsibility, and alone would provision Marion and pay the officers and crew.11 The Secretary of War hoped that, with the resulting decrease in expenditures, Whitehead’s surplus could be used to pay troops recently stationed at Key West. After he learned of the idea, Whitehead declared that he was willing to make it “practicable … if the Department consider it requisite,” but cautioned that success would depend on “the commerce of the place,” itself “not of a character sufficiently regular to judge of the amount of spare funds there may be on hand….”12

The plan to end Whitehead’s oversight of Marion must have been postponed, if not abandoned, for he invited proposals and signed contracts to provision the cutter for the coming year, and for the year after. With a government ceiling of twenty-three cents per ration he feared there would be no offers; the Treasury agreed to allow two cents more, but a Key West merchant quoted him a price within the prevailing limit. Whitehead even shaved a penny off the price in the following year’s contract, leaving no doubt of his commitment to economize.13

Marion’s protracted absences from the Key West district were the unavoidable result of a cruising ground that reached from the Gulf of Mexico to the Carolinas. A scheme whereby two cutters sailed between Key West and Charleston in opposite directions, calling at one or the other port every seventy-five days, seems to have had a haphazard implementation, if any.14 From May through late October of Whitehead’s first year, no revenue cutter is known to have visited the harbor at Key West.15

For this reason, Whitehead asked that a cutter be expressly assigned to the Florida Reef. Such a commitment would free a Charleston-based cutter from having to cover so much ground, render more efficient service to mariners, merchants and the revenue, and forge better links along the seaboard between Key West and other harbors. It would at the same time facilitate contact of government officials like himself with their departments.16

But Marion, Whitehead was compelled to state, was not, for all her nimbleness and speed, up to the job. Drawing 9½ feet of water, she couldn’t navigate the shallow coastal inlets and tight spaces so beloved of smugglers, or find safe anchorage at times of “boisterous weather.”17 The collector had opportunities to observe this problem firsthand, and urged that one of a new generation of light-draft cutters be reserved for the Keys.18

He probably visited the vessel several times, but Whitehead’s writings speak of only three voyages aboard Marion during his first year as collector. On a weeklong cruise in May 1831, he spent a day in Havana and two in the Dry Tortugas, inspecting the lighthouse there. In November, Captain Jackson brought him on an eight-day fact-finding mission to the Spanish fisheries on the Gulf Coast, where one of Marion’s two boats steered him through the narrow passages and around the islets of Charlotte Harbor. Returning for a brief stopover at Key West, Marion set out at the beginning of December, again with Whitehead aboard, for a longer visit to Cuba. The cutter came back from Havana with two seamen from an American brig as prisoners. Charged with attempting to lead a mutiny, the pair were kept “on board in irons,” a potent reminder that even officers of the revenue had to anticipate unruliness from their crews.19

Early in 1832, Jackson stepped aside. Robert Day, one of the two lieutenants accused of election fraud in 1829, was promoted in his place.20 With Day at the helm, Whitehead made perhaps his most consequential journey on board Marion, leaving Key West in April for Charleston, and continuing by land to points north,21 a trip that domestically speaking “added new ties and strengthened old ones.”22

His ties to Marion, meanwhile, were set to unravel. A few days after Whitehead left Charleston, John James Audubon boarded Captain Day’s Marion for an exploratory tour to the Keys and back. The ornithologist and artist would later recall how the cutter, “like a sea-bird, with extended wings, swept through the waters, gently inclining to either side….”23 Audubon’s memorable presence and Whitehead’s extended absence seem to have postponed, at least for some months, Marion’s surrender to the collector of Mobile.24 She may still have had occasion to visit Key West after that transfer was made, but it’s doubtful Whitehead ever took flight again aboard the Lady of the Green Mantle.

Copyright © 2024-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

[1] “The Lady of the Green Mantle” was, according to Audubon, an epithet given Marion by “the wreckers and smugglers” of the Keys; it is otherwise unknown. John James Audubon, Ornithological biography, or an account of the habits of the birds of the United States of America; accompanied by descriptions of the objects represented in the work entitled The birds of America, and interspersed with delineations of American scenery and manners 2 (Edinburgh 1834) 314n; 3 (Edinburgh 1835; hereafter “Ornithological biography 3”) 263. It has been suggested that Marion was adorned with a female figurehead thus attired: see John Viele, The Florida Keys 2: True stories of the perilous straits (Sarasota, Fla. 1999) 129. A reference to the character with the same sobriquet in Sir Walter Scott’s Redgauntlet (1824) is not unthinkable.

[2] S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 19 November 1830, to Wm. A. Whitehead; W. A. Whitehead, Perth Amboy 24 November 1830, to Samuel D. Ingham, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West, Dec. 13, 1826 to Mar. 29, 1833,” Correspondence of the Secretary of the Treasury with Collectors of Customs, 1789–1833. Record Group 56, General Records of the Department of the Treasury, National Archives and Records Administration, Microcopy 178, Roll 38 (Washington 1956; hereafter “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West”), pages 57, 60. Much of the correspondence in this series was copied by Whitehead from the Key West custom house files, and transmitted to Washington to replace papers lost in the Treasury building fire of 31 March 1833.

[3] On 9 December, Whitehead wrote to notify the Secretary of the Treasury that he had reached Baltimore. He next wrote from Key West that, “from the length of my passage hither,” he was unable to take up his duties before 24 January. W. A. Whitehead, Baltimore 9 December 1830, to Samuel D. Ingham; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 25 January 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham, both in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 73-74. For the voyage of the schooner Evan T. Ellicott, see my earlier post 039–Fishermen’s friend.

[4] By this time Marion had not visited for “about three months,” according to Whitehead. The cutter’s return is recorded on 9 February 1831 by William R. Hackley, Diary, in Goulding Collection, Special Collections, Florida State University Libraries, Tallahassee, MSS 0-128, and one day later by Whitehead himself. W. A. Whitehead, Key West 7 February 1831, to S. D. Ingham; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 19 February 1831, to S. D. Ingham, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 97, 99.

[5] Richard Rush, Treasury Department 12 May 1827, to J. Doane, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 8.

[6] In December 1826, Doane sent one of his lieutenants and an armed crew to secure the leaders of an uprising on board the slave ship Governor Strong, grounded off Key West while en route to New Orleans; see Charleston (S.C.) courier 25 December 1826 2:5. In the crisis occasioned by the wreck of the slave ship Guerrero (which serves as background to my previous post 093–Out of the depths), William Pinkney expected no help from Marion, her captain having, “with his usual disregard of his instructions,” sailed for St. Mary’s, Georgia, earlier in the month. But Doane did eventually return and helped to guard against attempts to abduct the captive Africans; he later escorted them to relative safety in St. Augustine. W. Pinkney, Key West 23 December 1827, to Richard Rush; Waters Smith, St. Augustine 2 April 1828, to Richard Rush: both in Charles Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIII. The territory of Florida 1824-1828 (Washington 1958; hereafter “Territorial papers XXIII”) 956-958, 1058-1059. The circumstances of Pinkney’s seizure of Marion are unclear: he was ordered to release the cutter to her new commander, Captain John Jackson, in December 1828. Apparently Pinkney’s successor seized Marion again the following year, after fraudulent voting by officers and members of her crew; Jackson then allegedly commandeered the cutter Pulaski for a dubious mission to Havana. Richard Rush, Treasury Department 22 December 1828, to Wm. Pinkney; affidavit of P. C. Greene, Key West 8 August 1829, both in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 22, 29 and 32.

[7] In the May 1829 election for Florida’s delegate to Congress, it was claimed that 18 to 20 of Marion’s crew were brought ashore and told to vote for Joseph M. White, the incumbent; some who refused had their whiskey rations stopped. The Key West Register expressed the belief that Captain Jackson had not “used or exercised any improper influence” in this affair, but had acted “with the utmost circumspection and magnanimity.” In a contest the following month, for Monroe County’s representative to the territorial legislature, Jackson was said to have “remonstrated in the warmest manner because his men had not been permitted to vote,” and it was maintained that 15 or 20 of them fraudulently did so. Theodore Owens, Key West 8 August 1829, to Andrew Jackson; affidavits of Samuel Sanderson, Key West 6 August 1829, P. C. Greene, Key West 8 August 1829, Joseph Prime, Key West 8 August 1829, all in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 28-31; Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIV. The territory of Florida 1828-1834 (Washington 1959) 256-258; Key West (Fla.) register, and commercial advertiser 4 June 1829 2:4. The Secretary of the Treasury ordered a “strict & impartial investigation into the truth” of these and other charges against John Jackson, with a final report submitted to the Department: D. S. Ingham, Treasury Department 31 October 1829, to A. S. Thruston, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 37.

[8] A. B. Fontaine, Key West 1 October 1830, to Secretary of the Treasury, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 54. A year and four months into his term, while in Washington, Thruston was directed to deposit any surplus in the Bank of the United States, and to “pursue the same course hereafter, as often as the departure of the Cutter from Key West for the U. States may afford an opportunity.” S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 20 September 1830, to A. S. Thruston, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 52. Such had been Treasury policy for the entire tenure of his predecessor at the custom house, who however seems to have disregarded it, and Thruston may have likewise failed to comply. Whitehead received identical instructions as he was about to assume the office. See Richard Rush, Treasury Department 14 April 1826, to Wm. Pinkney; J. Doane, Marion 9 June 1827, to Wm. Pinkney (including an extract of a prior order from Rush); J. Doane, Marion 28 June 1827, to Richard Rush; Richard Rush, Treasury Department 11 July 1827, to Wm. Pinkney; S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 31 December 1830, to Wm. A. Whitehead; all in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 2, 5, 9, 10, 58.

[9] W. A. Whitehead, Key West 12 February 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 19 February 1831, to S. D. Ingham, enclosing copies of correspondence with commanders Joseph Swiler of Pulaski and John Jackson of Marion; S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 22 March 1831, to W. A. Whitehead, all in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 98, 99-101 and 65.

[10] S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 18 November 1830, to Collector of the Customs, Key West, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 56. The date of Whitehead’s appointment given by Peter Force, The national calendar, and annals of the United States; for MDCCCXXXII (Washington 1832) 189 is confirmed by a portion of his commission preserved in the papers of his son, Cortlandt Whitehead, in the archives of the Diocese of Pittsburgh.

[11] S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 5 February 1831, to Collector of the Customs, Key West, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 62.

[12] S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 22 March 1831, to W. A. Whitehead; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 12 April 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham, both in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 65 and 104.

[13] Key West (Fla.) gazette 20 April 1831 4:3, 4 April 1832 2:2; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 12 April 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 2 May 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham; S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 16 May 1831, to W. A. Whitehead; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 3 April 1832, to Louis McLane, all in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 104, 106, 68, 113.

[14] Because the cutter South Carolina, built at Charleston in 1829, shared this stretch of the coast with Marion, the Treasury thought it “proper that their cruize be so regulated that they alternate with each other” between the two ports. The situation on Whitehead’s arrival at Key West led him to inquire “whether that regulation still exists,” for Marion’s departure effectively left “the important points in this neighborhood entirely unguarded four months–which is the usual time taken for her cruizes.” S. D. Ingham, Treasury Department 6 February 1830, to A. S. Thruston; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 7 February 1831, to S. D. Ingham, both in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 44 and 97.

[15] “At present,” wrote Whitehead of Marion, “there is only one Cutter cruizing between this Port and North Carolina, and from the ground she has to go over, her trips between the most distant points are necessarily very much prolonged, and as her returns here are at stated times, they who may be engaged in illicit commerce on the Coast can make their calculations accordingly. She has not been here since early in May.” W. A. Whitehead, Key West 18 August 1831, to Asbury Dickins, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 109. Marion called at Key West on 29 April, then on 27 October: see “Marine intelligence,” Key West gazette 4 May 1831 3:2, 2 November 1831 3:1. No issues of the Gazette were published between 8 June and 13 October, but the cutter appears to have remained in more northerly waters in that interval: see “Ship news,” Charleston courier 2 August 1831 2:5, 18 August 1831 3:1.

[16] W. A. Whitehead, Key West 18 August 1831, to Asbury Dickins, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 109.

[17] Whitehead’s predecessor Thruston had already complained to the Treasury Department of Marion’s draft of water, which rendered her incapable of navigating the Florida coast’s many shoals and inlets. Whitehead observed in addition that competent pilots couldn’t be found to work for the low wages allowed, and urged that the cutters’ commanders be permitted to hire pilots “without limiting them as to terms….” A. S. Thruston, Key West 2 September 1829, to S. D. Ingham; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 1 March 1831, to Samuel D. Ingham; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 18 August 1831, to Asbury Dickins, all in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” pages 92, 102, 109.

[18] Whitehead noted hopefully “that several vessels are now building for the Cutter service,” probably a reference to those of the Morris class, of which thirteen were constructed beginning in 1830. The Treasury stationed Washington, one of the last of this class to be commissioned, at Key West, but not before 1833. In January 1836, Washington was with several other cutters placed under Navy Department orders for use in the Second Seminole War. She was released for repairs in April 1837, by which time Whitehead no longer believed a cutter permanently located in the Key West district was necessary. W. A. Whitehead, Key West 18 August 1831, to Asbury Dickins, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 109. W. A. Whitehead, Key West 27 February 1836, to Levi Woodbury; W. A. Whitehead, Key West 27 April 1837, to Levi Woodbury, both in “Letters from Collectors on Revenue Marine,” Letters received from Collectors of the Customs, Record Group 26, Records of the United States Coast Guard, National Archives and Records Administration, Box 2, page 36; Box 3, page 64.

[19] Whitehead recorded all three cruises in the journal Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water (hereafter “Memorandums”), Volume 2, pages 88-100, held by the Key West Art & Historical Society. His picturesque narrative of the Charlotte Harbor mission occupies most of these pages; it served as the basis for “Charlotte Harbor forty-seven years ago,” a two-part installment in the series Reminiscences of Key West, Nos. 11-12, published in Key of the Gulf (Key West, Fla.) 16 and 30(?) June 1877, and reprinted in Thelma Peters, ed. “William Adee Whitehead’s Reminiscences of Key West,” Tequesta 1:25 (1965) (3-42) 33-38. His trip to Charlotte Harbor is detailed in my earlier post 039–Fishermen’s friend. For the December visit to Havana, see the service log of Marion, in Logs of Revenue Cutters and Coast Guard Vessels, 1819-1941, Record Group 26, Records of the United States Coast Guard, National Archives and Records Administration, entries of 2-8 December 1831; Key West gazette 14 December 1831 2:3, 2:4; and my post 092–An exacting business, especially note 20.

[20] Day must have considered an advancement long overdue: he had sought command of a cutter more than a year earlier, after almost six years as a lieutenant on Marion. Robert Day, Marion 13 December 1830, to Andrew Donaldson [Donelson], Andrew Jackson Donelson Papers, 1779-1943, Library of Congress. John Jackson was assigned to the cutter Crawford at Savannah, then given command of McLane in the summer of 1832. He captained Jefferson in 1836 during the Second Seminole War. Louis McLane, Treasury Department 27 April 1832, to W. A. Whitehead, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 77; Charleston courier 18 September 1832 2:3; “Revenue Marine in the Seminole or Florida War, 1836-1842,” Record of extraordinary operations and legislation, 1789-1871, Record Group 26, Records of the United States Coast Guard, National Archives and Records Administration, page 156.

[21] “Marine intelligence,” Key West gazette 11 April 1832 2:4; “Ship news,” Charleston courier 13 April 1832 2:5. Whitehead’s journey from Charleston to Washington is related in Memorandums 101 et seqq.

[22] With his return to Key West that October, Whitehead became ever more conscious of inhabiting “a bachelor’s establishment.” He and Margaret Parker were married in Perth Amboy in August 1834. Typewritten transcription of an unpublished memoir, “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” of which the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, hold copies. Pages 34-35 contain the references.

[23] “The wreckers of Florida,” Ornithological biography 3:158. Audubon’s 1832 sojourn in the Florida Keys is the topic of a previous post, 041–The collectors (part 1).

[24] Late in April, the Secretary of the Treasury addressed an order to Marion’s commanding officer (not named) to report to the collector at Mobile and turn over the vessel “to such officer as he may direct”; the message was sent to the care of Whitehead, however, who had left Key West on the 7th, and Marion was under orders to take the naturalist back to Charleston at the end of his explorations. Audubon departed aboard Marion on 21 May, and the cutter is found arriving from Mobile under a new commander on 5 September 1832. Louis McLane, Treasury Department 27 April 1832, to W. A. Whitehead, in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West,” page 77; “Mr. Audubon,” Key West gazette 23 May 1832 2:1-2; “Marine intelligence,” Key West gazette 23 May 1832 2:2; Key West gazette 5/8 September 1832 2:2.