“OLD Neptune,” for most of the five-day sail, kept William A. Whitehead firmly “under his thumb.” The collector, no doubt relieved to plant his feet on terra firma once more, savored this moment even in his weakened state. He had endured the first leg of a long-anticipated homeward journey (to his parents’ home, at least, if no longer fully his own) and would soon strike out for the interior, to continue north at a safe remove from the sea.1

Before taking leave of Charleston, Whitehead had a few days to make calls, deliver others’ letters, post his own, and tour this Southern metropolis through which passed most of the news that reached him on Key West. From the start of his sojourn in the dining room of Jones’s Hotel, where he relished a first meal of fresh lamb with green peas, the city revealed itself a nest of contradictions.

Situated on Broad Street, hard by the venerable St. Michael’s Church, the inn was a favored resort of upper-class patrons from around the United States and abroad. The wealth amassed by proprietor Jehu Jones included choice lots in the commercial center, and enslaved workers in sufficient numbers to assure, “not only the comforts of a private house, but a table spread with every luxury that the country afforded.” And yet, South Carolina’s draconian laws regarding free Blacks compelled Jones, a free Charlestonian of color, to part with his wealth, his status and his business, and to live out his days a Northern exile.2

Charleston’s gardens in April 1832 were abloom with their famed azaleas, but Whitehead strolled or rode about the town looking more to the built environment, observing the contrasts from what he knew. He was unimpressed by the preference for walls of unpainted brick, or the ubiquitous single houses with their covered porches or “piazzas” on the sides, gable ends facing the street. Hardly one to disparage memorials of the past, Whitehead found these elements conveyed to a Northerner “a very old & rather a dilapidated appearance”; his sense of the city overall was of a provincial, rather forlorn antiquity.3

At the east end of Broad Street stood the Exchange, a neoclassical vestige of South Carolina’s waning years as a British province. Built as a custom house, it still functioned in that role but with appreciably less traffic than a decade ago; the Exchange also accommodated the post office. Slave auctions were a common sight on its steps or in its shadow, and a few summers hence, bundles of antislavery literature would be hauled out of it and publicly burned. Though sturdy and spacious, in Whitehead’s eyes the Exchange wore “the stamp of age in all its features.” Of the newer public buildings he saw “none very remarkable for their beauty.”

From such descriptions emerges the profile of a city trapped in the past, too conservative or too unambitious to arrest and reverse its steady decline. But this wasn’t the whole story. Whitehead arrived in South Carolina fully conscious that the state and its chief port were at the center of an ongoing emergency.4 Anti-tariff sentiment was gaining ground in this and neighboring states through most of Whitehead’s first year as collector. The majority of politicians had by now fallen in line, objecting to the federal tariff as fueling Northern prosperity, while doing grave injury to the South. The theory that individual states could interpose or “nullify” a federal law on constitutional grounds had recently gained South Carolina’s favorite son, Vice President John C. Calhoun, as its foremost advocate.

Key West’s only newspaper, edited by Charlestonian Benjamin B. Strobel, had kept the crisis before its readers, taking a firm “State Rights” position, but standing by President Andrew Jackson as the leader best able to “chain down that bitter spirit of contention, which threatens to tear asunder this Union.…”5 Without dismissing the just grievances of the South, Strobel looked for conciliatory signs from the North that would help to stem the tide of nullification.

Whitehead, whose responsibility it was to enforce the terms of the tariff at Key West, maintained a studied silence in public. But the issue must have dominated his conversations with merchants, and he may well have conferred with his counterpart at the Charleston custom house, the epicenter of any eventual showdown between South Carolina and the central government.

Although time was too short “to profit by the civilities South Carolinian politeness would extend to me,” Whitehead found edification and enjoyment in a musical performance from “a German gentleman boarding in the house” whose name is unfortunately not preserved. This musician had perhaps been drawn to the city’s well-established German immigrant community, of whom one member, the young botanist Edward Frederick Leitner, was to be a friend to Whitehead and a regular presence in the Florida Keys, beginning the following winter.6

Whitehead declared the unnamed musician, who sang and accompanied himself on the guitar, “the best performer on the instrument I ever heard….” After playing a composition of his own that had won a prix d’or in France, he led hotel guests in the Marseillaise and other national hymns. Every educated German Whitehead had met seemed to have some measure of musical taste or ability: “I hope more attention will be paid to it in the U. S.,” he wrote. “It is getting very fast to be almost necessary to any one who wishes to succeed.”

Very different rhythms had, in recent years, caught the attention of South Carolina capitalists and city officials, bent on reviving Charleston’s commercial life and restoring the value of their property. Rather than expend energy blaming their decline on the industrializing North, they looked to its example, and in 1828 launched the first railroad south of the Potomac. As subscription books were opened, one newspaper exulted:

Thus shall the departed prosperity of our City be recalled, and the visions of increasing splendour and importance, which once cheered our sight and animated our hearts, but which have so long faded away before a chilling gloom and a lifeless inactivity, beam again with refreshened brightness, and with even more inciting allurements.7

The year 1832 brought a concerted push to expand the line to its full 136-mile length, ending at Hamburg on the Savannah River. Once complete, it was the longest railroad in the world, but the segment of which Whitehead could avail himself extended only the first twelve miles. Because trains were not allowed to enter Charleston proper, he was obliged to travel more than two miles from his lodgings to reach the terminus; fear of missing his early morning departure kept Whitehead awake the entire night.

The train ran on lengths of strap iron bolted to wooden tracks; these were supported by wood pilings driven into the soft earth. While the line remained under construction, passengers typically rode in a covered conveyance joined to other cars for transporting workmen and materials.8 There’s no mention of separate cars, or of tracks, in Whitehead’s recollections; considering the detailed notes he made of early railroads in the North, the omissions may be imputed to sleep deprivation.

What Whitehead did think to mention was the most important advance of the Charleston-to-Hamburg railroad. After experimenting with different kinds of “motive power,” from human to animal to wind, the incorporators had settled on an engine powered by steam, a harbinger of transportation’s future as well as Whitehead’s own.9

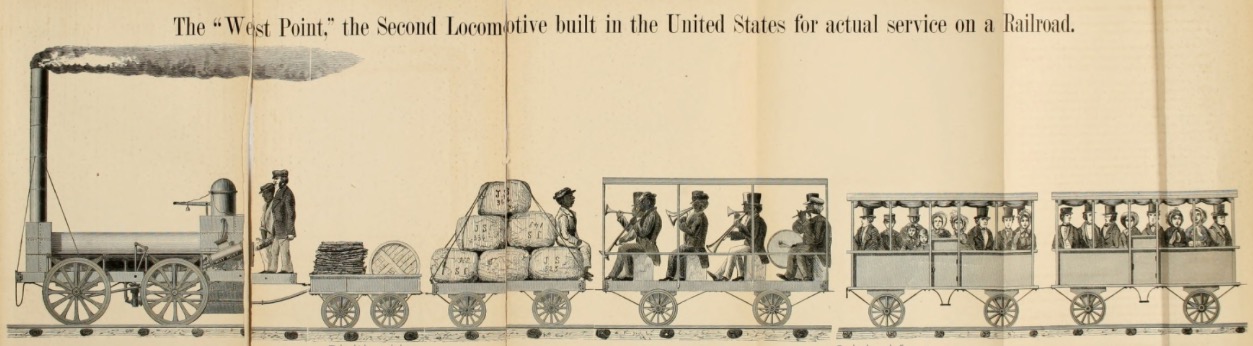

It’s unknown which of the New York-built locomotives was in service on this day. Because Whitehead was told, or remembered being told, that the engine could “with perfect safety” attain a remarkable speed of 50 to 60 miles per hour, it may have been the more powerful of two, the brand-new twin-boiler South Carolina and not the year-old West Point. Such high speeds would not be cost-effective, it was explained, given “the limited extent now travelled,” but, in view of the mechanical failures and accidents to which engines and cars were prone, we may be glad his train proceeded more cautiously, taking roughly an hour to make the 12-mile run.10

A projected branch line to Columbia, the state capital, existed for now only on paper, and it would take years to establish a rail connection to the North. Whitehead’s route from Lowcountry to Piedmont relied therefore on roads, bridges and ferries subject to the caprices of men and of nature. The “thumping, bouncing and jostling” all day and through the following night meant bad sleep or no sleep at all.

After the previous night’s wakefulness, exhaustion made close observation impossible: “my eyes seemed each to be covered with a leaden weight and no sooner had I by a great exertion opened one and caught a glimpse of the ‘sickly moon,’ than it closed again ere its fellow could be brought to its support.” Not that there was much for either eye to see, other than miles and miles of pine woods, punctuated by an occasional small field of grain or cotton patch. Material progress in these parts must have seemed, to most eyes, a distant prospect indeed.

Copyright © 2024-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

[1] Whitehead’s days in Charleston (12-16 April 1832) and land journey northward are known (so far) only from his journal Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement, vol. 2nd, held by the Key West Art & Historical Society. The section headed “From Key West to the North,” on which most of the following is based, consists of entries dated 12 April through 2 May: its first page is numbered 101, the rest are unnumbered. An undiscovered Volume 3 would have continued the narrative further into May, at least as far as his departure from Washington, on or about the 10th; it may have gone on to describe a summertime trip to New England and other travels. Whitehead didn’t return to Key West until 12 October.

[2] F. C. Adams, Manuel Pereira; or, the sovereign rule of South Carolina. With views of Southern laws, life, and hospitality (Washington 1853) 88-89. Petitions to the state legislature show that, after a visit to New York in 1823, Jehu Jones’s wife Abigail, her daughter, two grandchildren and an enslaved servant were refused permission to re-enter South Carolina under state law. The appeals of some 90 white petitioners, including Charleston postmaster Alfred Huger, to allow the family to return or permit Jones to visit them were unavailing, and in 1832 Jones left the state to take a position teaching and editing a newspaper for the American Colonization Society. He soon found, however, that “promises of great Remuneration in money & valuable Lands” in Liberia were “merely a delusion,” leaving him “among strangers jealous of new commers, without friends, without funds & without Employment.” After eight years of struggle in the North, Jones begged leave “to visit the grave of my Father, the spot where I was Born, grew up & lived respectably for Nearly half a Centry.” The request doesn’t appear to have been granted. General Assembly Petitions, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, S165015, nos. 130 and 138 (6 December 1823), 102 (6 November 1827), 47 (October 1840), 1867, 1871 and 1872 (no date). See Marina Wikramanayake, A world in shadow. The free Black in antebellum South Carolina (Columbia, S.C. 1973) 177-178.

[3] It is a view corroborated by many travelers, among them Irish actor Tyrone Power, who perceived Charleston “to be just in the condition the English army left it; I did not see a large house that appeared of newer date; and the churches, guard-house, &c. must be the same.” Impressions of America, during the years 1833, 1834, and 1835 (2 vols. London 1836) 2:97-98.

[4] Unitarian minister Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch’s recollections are instructive: “Among my first impressions of Charleston, the sense of insecurity on the part of its inhabitants held a place. The city seemed to be in a permanent state of siege. The police were in military uniform, and one of these seeming soldiers was stationed in the porch of each church during the time of service. At evening, close following a sweet chime from St. Michael’s, resounded the drum-beat, signal to the black population that they must no longer be found abroad.” S. G. B., “Reminiscences of Charleston, S. C. 1830-1832,” The monthly religious magazine 25:2 (February 1861) (111-124; hereafter “S. G. B., ‘Reminiscences of Charleston’”) 113.

[5] “To the public,” Key West (Fla.) gazette 21/28 March 1831 2:2. Cf. Key West gazette 13 (12?) October 1831 2:2-3; “The tariff,” Key West gazette 25 January 1832 2:1-2; “John Q. Adams,” Key West gazette 1 February 1832 2:1-2; “Mr. Clay’s speech,” Key West gazette 8 February 1832 2:2-3; Key West gazette 29 February 1832 2:1, 2 May 1832 2:4.

[6] Leitner’s brief but extraordinary career was featured in my previous post 042–The collectors (part 2).

[7] City gazette and commercial daily advertiser (Charleston, S.C.) 18 March 1828 2:3. The depressed conditions of the 1820s were not forgotten, even after completion of the first branch: cf. Elias Horry, An address respecting the Charleston & Hamburgh rail-road; and on the rail-road system, as regards a large portion of the Southern and Western States of the North-American Union. …. Delivered in Charleston, at the Medical College of the State of So. Caro. on Wednesday, the 2d October, 1833. On the completion of the road (Charleston 1833) 4.

[8] Samuel Melanchthon Derrick, Centennial history of South Carolina Railroad (Columbia, S.C. 1930; hereafter “Derrick, Centennial history”) 40-42. The system of pilings didn’t last, and was gradually replaced by embankments and trestles.

[9] Derrick, Centennial history 42-47. The first locomotive on the line, known as Best Friend of Charleston, was placed in service in 1830 but sidelined in 1831 after its boiler burst. For this incident and developments down to the time of Whitehead’s journey, see Derrick, Centennial history 82-98.

[10] Broken axles caused two accidents just before and just after Whitehead’s ride: the first slightly injured the governor of South Carolina, the second hurled some 30 passengers into the mire, seriously injuring several. Charleston (S.C.) courier 16 April 1832 2:2, 23 April 1832 2:2.