DELEGATES, invigorated by a recent electoral victory, gathered in Columbia in November 1832 and decreed that federal tariffs would be null and void within the borders of their state. In so doing, they brought South Carolina to the threshold of armed conflict with Washington. On the heels of another election, twenty-eight years later, a similar vote in the same city pushed her over the brink.

In the account of his youthful “peregrinations,” William A. Whitehead recalled a visit to Columbia of only two days in the spring of 1832; his sojourn in the state lasted barely a week.1 If any of that year’s turmoil penetrated his road weariness, he didn’t write of it, at least in what has been preserved. He was perplexed, however, on his arrival from Charleston in the overnight stage to learn that John Taylor, a leading citizen and former governor to whom he bore letters of introduction, had unceremoniously died the same day, in a town some 30 miles away.2

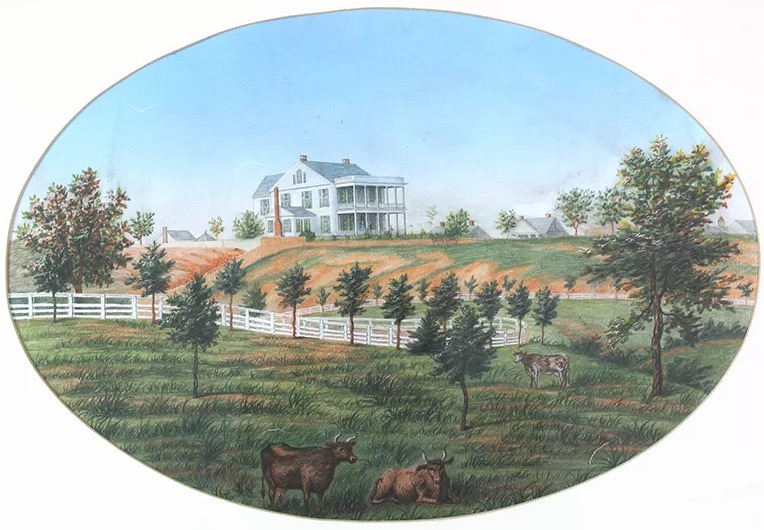

Whitehead lingered long enough in Columbia to admire just a few attractive features of the two-mile-square city: the state asylum built to the design of the pioneering architect Robert Mills, the South Carolina College, and a handful of churches. The veranda of the late Governor Taylor’s house, which crowned the elevation known as Taylor’s Hill, afforded a “very fine” view over “rather a pleasant looking town than otherwise,” spread out along the waters of the Broad and Saluda Rivers, where they mingled to form the Congaree.

South Carolina’s capital, situated by design at the head of navigation, served as a natural gateway between the interior and the coast for transporting cotton and other cash crops, as well as slaves. Its rivers were broken by falls and rapids and dotted with mills, for Columbia stood with many cities and towns as a concession to the logic of the fall line, that physiographic boundary dividing the coastal plain from the uplands to the north and west. Since its founding, the growth of the capital had also borne mute witness to the labor of countless unknown hands, including South Carolina’s Black and largely enslaved majority.

On 19 April 1832, Whitehead set out on the noon stage for Camden, the first of several towns he would pass through, on an itinerary clinging generally to the fall line. While the route included stations to change coaches, horses and drivers, stops where he might also refresh himself, he would traverse parts of three states over more than three days before laying his head down for a full night’s rest.

The pace far exceeded that of a hero of the Revolution and of his boyhood, the Marquis de Lafayette, whose farewell tour of the South in 1825 partly followed the same route in reverse.3 The French nobleman, when not slowed by drenching rains or impassable roads, was obliged to greet crowds of admirers and accept repeated demonstrations of public affection.

Whitehead was detained by no receptions of this sort, but endured with his distinguished precursor the same pathways cut through thick pine forests, the same long stretches of unvarying scenery by day and eerie darkness by night. Over the two hundred wearying miles beyond Camden, he noted “little to attract the attention of the traveller” beyond the bloom of an occasional dogwood tree, a patch of honeysuckle, or “a small wild flower” to ease the monotony.

Whitehead recorded brief stops in the North Carolina cities of Fayetteville, the first anywhere to be named for Lafayette, and Raleigh, the purpose-built capital. The year before, both places had suffered calamities: Fayetteville being largely wiped out by fire, and the state house in Raleigh burning down a month later. The ruins of the latter were still to be seen, and Whitehead heard talk of the capital moving to Fayetteville, much the larger of the two cities, which had enjoyed that distinction prior to 1794. Indeed, Raleigh’s future as the capital was to hang in the balance for several months to come.

Further ahead, the scenery was more varied, but torrential rains had made the roads decidedly worse. At 9 pm on the 22nd, Whitehead reached the prosperous town of Petersburg, Virginia, below the falls of the Appomattox. Lafayette had rested here, and after riding day and night the 361 miles from Columbia, so too did Whitehead, “in order to recruit in some measure my forces; constant travelling,” he confessed, “having considerably diminished them.” The bed of his hotel, probably on Bollingbrook Street where Lafayette also had stayed, “felt so peculiarly delightful that I had not time to make any survey of the Town before I took my departure for Richmond,” a mere 22 miles due north.

The Virginia capital wanted more attention than Whitehead had time to give, but he praised its appealing situation on the River James, its many attractive private homes, and its stately neoclassical Capitol building, “from which there is a delightful prospect of the country around.”

On a seat in the overnight mail coach from Richmond northward, Whitehead undertook the last stage of his voyage along the thoroughfares of the South. He passed through a landscape of rolling hills, dotted with plantation homes “handsomely situated,” but was unimpressed with the quality of cultivation. The farms, bounded by the serpentine “Virginia fence” or no fence at all, displayed none of the “neatness and air of finish” seen on farms in the North. Whitehead recorded this apparent disparity without thinking to account for it.

Later in the day he dined in Fredericksburg. Anticipating Lafayette’s arrival here in 1824, city fathers had ordered all but white adults from the streets through which the Nation’s Guest would pass.4 They made, of course, no such provision for Whitehead, assuring a more balanced perspective of the town and its people. But he made no note of either. As almost everywhere in his narrative, the human factor has to be inferred: no ink is ever spent over laborers in the fields and forests along Whitehead’s route, or on the coachmen, stable hands, porters and cooks who populated the background of so long and taxing a journey. It’s not the way of most passengers, after all, to be concerned with how they get where they’re going, only how fast and how comfortably.

Once over the Rappahannock, Whitehead had only nine miles to reach the landing at Belle Plain. His final sixty miles would be “performed by steam,” on a course up the broad Potomac to Washington.5 He set foot in the federal city at 10 o’clock the night of the 24th, and awoke the next morning to the sight of the Capitol dome before a sunlit sky. Captivated by “its elevated situation, its dazzling whiteness, the beauty of the surrounding grounds, taken in connection with the purposes to which it is applied,” he could not have found a sight as entrancing, or an omen for his visit as favorable.

Some cities along the fall line may have appeared more flourishing, but none mattered more to Whitehead’s journey or the retelling of it. At the seat of Congress, “the palladium of our liberties,” and in the various executive departments, people would at last take center stage.

The hope of these encounters had sped him over so much sparsely inhabited and even unpropitious ground, and Washington’s vistas now inspired the most elevated thoughts. Here the nation’s ideals of liberty and equality were solemnly enshrined, if far from perfectly realized. The prayer of “some Senator” came to mind (his name unfortunately did not), which Whitehead approvingly repeated: “when the Genius of Liberty shall depart if ever she does from our happy land, may the dome of the Capitol be the last place whence she shall wing her flight.”

Copyright © 2024-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

[1] Whitehead’s account of his April 1832 journey through the Carolinas and Virginia forms part of his Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement, vol. 2nd, a manuscript memoir held by the Key West Art & Historical Society. The volume’s pages, beginning at his departure from Charleston for Columbia, were left unnumbered.

[2] Whitehead gives the distance from Columbia to Camden, where Taylor was visiting at the time of his death, as only 22 miles. His list of stops and miles between them appears to be fairly accurate otherwise, judging from what I’ve been able to learn of the stage routes of the day: “Camden to Cheraw 68; Cheraw to Fayetteville 55; Fayetteville to Raleigh 68 miles; Raleigh to Petersburg 148.”

[3] Having barely missed Lafayette’s 1824 arrival in New York City, a 14-year-old Whitehead paid homage to the Hero of Two Worlds in New Jersey six weeks later, walking four miles to do so. See my previous post 008–The hero’s welcome.

[4] “Arrangements for the reception of General La Fayette, in Fredericksburg,” The Virginia herald (Fredericksburg, Va.) 20 November 1824 3:3.

[5] I am grateful to Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor for clarifying Whitehead’s route from Fredericksburg and the location of the Potomac steamboat landing.