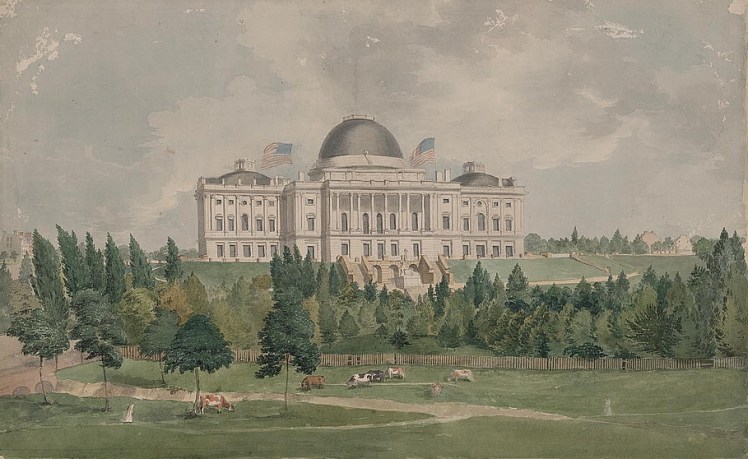

ON his first Washington visit, William A. Whitehead likely made his way to Capitol Hill as a pilgrim would, on foot. His approach from the west began at “two flights of steps laid in the slope of the eminence.” Above and before him, crowned by Charles Bulfinch’s copper-clad wooden dome–not the massive cupola familiar to us, but imposing nonetheless–rose the central portico of the Capitol building, the ultimate objective of his climb.1

A third set of stone steps ended on a level with the Capitol’s main floor, but Whitehead interrupted his ascent to inspect a monument recently placed on the landing “of beautiful white marble somewhat defaced….” Its lone column, surrounded on four sides by figures and standing on a stepped, square podium, and the podium on a stout square base, formed a peculiar composite of classical motifs and nationalistic allegory. The handiwork of an Italian sculptor, which was delivered to America in 1807, the Naval or Tripoli Monument commemorated six naval officers who, in one of the nation’s earliest foreign conflicts, died to protect American commerce from pirate attacks, and to safeguard the captains and crews of American merchant ships from being imprisoned and sold into slavery along the Barbary coast.2

Whitehead described the monument’s four figures and its podium:

Fame is represented as presenting the laurel crown, History as recording the deeds of the “brave dead,” America in the dress of an Indian is pointing out to a couple of children the example that has been set them, and Commerce laments the fall of her brave defenders. The Pedestal is ornamented by a view of the harbour of Tripoli and several inscriptions.

Had he mounted the same steps a year earlier, Whitehead would have found no monument here. Commissioned and paid for by the fallen officers’ comrades at the instigation of Lieutenant David Porter, himself a former prisoner at Tripoli, the work was destined for the Washington Navy Yard, which received it in 1808. During the British burning of the American capital six years later, it became the target of vandals, whose mischief Porter described years later in detail: “The Flames of the lamps of Glory, or Immortality, were taken away; the Palm snatched from the hand of Fame; the golden pen taken from the hand of History; the pointed forefinger of the hand of America broken off; as also was the ‘little end of the horn’ of Plenty, borne by Commerce.” Still showing the scars of this mutilation, the monument was transplanted to Capitol Hill in 1831 over Porter’s objections, and “placed,” to his great disgust, “in a small circular pond of dirty fresh water–not large enough for a duck puddle–to represent the Mediterranean Sea.”3

Whether the degradation was as severe as Porter perceived, it seems that a quarter-century from its initial reception the symbolism and even the significance of the Tripoli Monument were little appreciated. Since Whitehead, despite the damage, grasped the meanings of its component parts well enough, one may wonder what further associations came to his mind. Lieutenant Richard Somers, the most celebrated of the “brave dead,” was a fellow son of New Jersey.4 But in coming to Washington Whitehead had borne far more obvious ties–if tangled ones–to the very originator of this misunderstood homage in stone.

A decade earlier, Captain David Porter had turned his prior Mediterranean experience to the problem of piracy in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. The island of Key West became a naval station effectively under Porter’s control, and the expectations of its four proprietors, including Whitehead’s father, whose proxies were his older son John Whitehead and, later, William as well, had to be largely deferred until military rule ended.

For their losses during the years of Porter’s occupation, the Whiteheads sought compensation from the national government, and it was William’s private purpose while in Washington to find evidence “to effect favorably” that claim.5 Ironically, however, his public mission to lobby for Key West’s mercantile interests would benefit from Porter’s high opinion of the island’s strategic value.

At the summit of the third flight of stairs, Whitehead stood on a level with the legislative halls of the Capitol and its central Rotunda. On an engraved diagram he recorded meticulously the dimensions, horizontal and vertical, of each wing and chamber, ending with the diameter and height of the Rotunda: both 96 feet. (The height beneath the present dome is double that.)

Whitehead in April 1832 experienced the Rotunda as have many of its visitors, as a shrine to American heroes, their stories told in paintings and sculpture. A draftsman of some talent, he nevertheless expressed almost no opinion of these works’ artistic merits, even as some were the targets of sharp criticism in his day. Rather he confined himself to their didactic value, their capacity to instruct the viewer about past moments, and movements, thought to be of significance for the present.

The Rotunda, as Whitehead encountered it, neatly divided the American story between episodes of European exploration and colonization on the one hand, portrayed in sculpture, and the winning of independence on the other, celebrated in four large-scale paintings. No part of its narrative concerned the indigenous past before Europeans arrived, nor did the chronicle yet extend to events since the end of the Revolutionary War.

In line with the bifurcation of their works into two distinct epochs, the sculptors were Europeans, temporarily resident in or near Washington and working in local stone, while the painter (at this date there was but one) was the son of a Connecticut governor, trained in London by “the American Raphael,” Benjamin West.

Between the spaces allotted for paintings and the entablature of the Rotunda, Whitehead noted four oblong panels of sandstone, carved with festoons of flowers, wreaths, palm fronds and oak branches. At the center of each was a bas-relief portrait of a European explorer in profile–here were Columbus, John Cabot, La Salle and Walter Raleigh. Despite centuries of separation, Whitehead and his generation would have sensed a debt to all of them: even Columbus, who never set foot on the mainland, yet bequeathed to Americans, as Whitehead would one day write, “a country to love and honor.”6

In more varied sculptures above the north, south, east and west entrances to the Rotunda, the age of exploration yielded to the period of settlement. Each relief depicted an encounter between colonizers and colonized: two of them (Landing of the Pilgrims and William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians) were outwardly peaceful, one (Preservation of Captain Smith by Pocahontas) was a scene of violence narrowly averted, and one (Conflict of Daniel Boone and the Indians) of violence made manifest.

These reliefs were not to the liking of everyone: a distinguished architect of the day thought them in bad taste, recommending their replacement by paintings or inscriptions. Few would have questioned the underlying lesson, however, that the dislocation and eventual disappearance of the first inhabitants of these lands was foreordained. Whitehead assessed the sculptures merely from a technical viewpoint: “The figures in these bas reliefs are well executed but are too crowded to produce the effect they otherwise would.”7

Dominating one side of the Rotunda since 1826 were four large Revolutionary scenes by painter John Trumbull. (Trumbull, at age 70, prepared and campaigned vigorously for a commission to fill the remaining four recesses designated for paintings, but the work was given to other artists.) At least The Declaration of Independence, the first of Trumbull’s scenes and the best known, was probably already familiar to Whitehead from its exhibition in New York and other cities prior to installation in the Capitol, or from the 1823 engraving by Asher B. Durand, if not both. The other three works, in the order of their completion, portrayed the British surrenders at Yorktown and Saratoga, and George Washington’s voluntary resignation of his command at the successful conclusion of the war.

In the case of the Declaration, both painter and painting were criticized on many accounts, including an alleged lack of authenticity. Trumbull replied that he had “spared neither labour nor expense in obtaining his portraits from the living men,” and Whitehead found that the “great value” of all four canvases lay in the accuracy of their portraits, “being it is said mostly good likenesses.” His response to these imposing scenes, however, is surprisingly muted, and it’s not impossible that his view was affected by the storied antipathy between Trumbull and William Dunlap, a painter, art critic and historian with whom Whitehead had a birthday, a hometown and many interests in common.8

Whitehead left no other direct evidence of how the Capitol’s sculptures and paintings impressed or influenced him. But as a young citizen of the republic, an officer of its government, and an eager student of its origins, he would not have shut his eyes to such continuities as existed. It would be of dubious value to read works so disparate in origin and style, and so uneven in quality, as a programmatic whole. Yet, from the memorialization of American sacrifices off Tripoli’s shores to the image of the victorious general surrendering his command to retire to private life, the Capitol building through its art did seek to instill at least one unified and enduring principle: that this was a land consecrated to liberty, where no man–one hastens to add, no white man–should be a slave, nor any man a king.

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.07.01

[1] Details of Whitehead’s Washington sojourn, with tipped-in engravings of the plan of the city and the Capitol, and portraits of the President, Vice-President and Postmaster General, are preserved in his manuscript Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement, vol. 2nd, a volume held by the Key West Art & Historical Society. The section entitled “Sixteen Days in Washington” begins on 25 April 1832 and, unless otherwise noted, is the source of the information and quotations here; its pages were left unnumbered.

[2] The memorial’s history, iconography and misreadings are usefully laid out by Janet A. Headley, “The monument without a public. The case of the Tripoli Monument,” Winterthur portfolio 29:4 (Winter 1994) 247-264.

[3] “Mutilation of the monument, erected to the memory of those who fell before Tripoli,” Army and Navy chronicle 8:17 (25 April 1839) (258-262) 258.

[4] On the development of the Somers legend, see Robert E. Cray, Jr., “Remembering Richard Somers: naval martyrdom in the Tripolitan War,” The historian 68:2 (Summer 2006) 267-284.

[5] Typewritten transcription of an unpublished memoir under the title “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” of which copies are held by the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Pages 33-34 contain the reference. Whitehead would relate that, during Key West’s three-year occupation by the Navy, “the growth of the Town was considerably checked from its being most of the time under martial law”: Notices of Key West for John Rodman Esq. St. Augustine, written December 1835, manuscript copy in Florida Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection, P. K. Yonge Library of Florida History, 2b, printed in Rember W. Patrick, ed. “William Adee Whitehead’s description of Key West,” Tequesta: the journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida 1:12 (1952) (61-73) 64. On the fortunes of the proprietors during this period, see my earlier post 059–Gibraltar of the Gulf.

[6] W. A. Whitehead, “The resting place of the remains of Christopher Columbus,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society ser. 2, 5:3 (1878) (128-137) 128-129. For the honors that Whitehead had paid and would later seek to pay the Genoese admiral, see my earlier post 021–Dust and din. He correctly identified the Rotunda figures of Columbus, Raleigh and La Salle, although their names are inscribed in such a way that one must stand directly beneath the portraits to see them (in fact Whitehead wrote “La Sale,” as the inscription spells it). He did not see or remember the name of Cabot, leaving a blank in the manuscript where a later hand seems to have scribbled in pencil “Americus,” presumably for Amerigo Vespucci.

[7] Architect Robert Mills, whose buildings Whitehead a few days earlier had admired in South Carolina’s capital, would express his disdain for the Rotunda sculptures in his Guide to the Capitol of the United States, embracing every information useful to the visiter, whether on business or pleasure (Washington 1834) 29n. “How different,” he wrote, “is the effect on the eye contrasting this sculpture with the paintings below; the former is scarcely noticed, though representing deeply interesting subjects, while the eye dwells upon the latter with real pleasure and instruction.” For Whitehead’s brief visit to Columbia, see my previous post 096–The fall line.

[8] [John Trumbull,] Description of the four pictures, from subjects of the Revolution, painted by order of the government of the United States, and now placed in the Rotunda of the Capitol, 1827 (New York 1827) 8-9. For some account of Whitehead’s friendship with Dunlap, see my previous posts 009–Progress and place, 044–Barrow Street, and 045–The Dunlap benefit.