“OUR National Flag,” toasted William A. Whitehead, lifting a glass. “May the stars that compose its union forever remain united and as brilliant as they are now.” If, while standing to deliver this invocation, Whitehead seemed a little unsteady, there would have been neither scandal nor surprise, for in a sequence of thirty-five his toast was the twenty-first. The libations rounded out an elaborate feast, served to “a large and respectable number of persons” marking the centennial of George Washington’s birth. The meal itself was likely preceded and attended by a good amount of imbibing.1

To a degree the whole population, be it permanent or transient, shared in the “considerable spirit” with which Key West marked the occasion. Earlier in the day, the army post on the island fired a 13-gun salute; vessels in the harbor hoisted “the flags of their various nations”; every public building was draped in the American ensign; and invitations to the anniversary dinner had been given to select visitors, not just prominent citizens. One sojourner had sent along with his regrets a written homage to the warmth of Key West’s climate and people, incidentally lauding its recent elevation in status from town to city: “No section of the United States,” he gushed, “has so delightful a winter climate, and no city so great a proportion of intelligence and hospitality in its population.” For a place of a few hundred residents, remote from a city of any size, this was no faint praise.

A long succession of toasts was obligatory at gatherings of this kind. The first thirteen had been arranged in advance, beginning with one drunk to Washington’s memory “standing and in silence.” The affair soon became more boisterous: the number of hurrahs elicited was recorded in a future issue of the Key West Gazette. The final preset tribute, to “the American fair,” referred to that segment of the population kept safely apart from the proceedings so as to preserve the spirit of “good humour and cheerfulness.” Such observances tended to be exclusively male gatherings, but no toast was met with more cheers than this one.

Of the 22 “volunteer” toasts following those on the program, most, including Whitehead’s invocation of the flag, drew no cheers, or none was noted. But the third toast after Whitehead’s, a tribute to “our honorable and faithful Representative–May his services be appreciated,” won lively and prolonged acclaim. Joseph M. White garnered a remarkable six hurrahs.

Some years prior to these festivities, the town fathers had given to a road opposite the barracks the name of White Street–it’s believed for him.2 The tenor of that after-dinner toast suggested that Joseph White enjoyed less appreciation than he deserved, although the cheers seemed to prove otherwise. Who then was this “Representative,” and why did William Whitehead seek him out before all other officials upon arriving in Washington two months later?

Joseph Mills White hailed from Kentucky, the protégé and son-in-law of John Adair, that state’s eighth governor. Appointed to Florida’s first Legislative Council, White arrived at Pensacola in 1822 “by the same conveyance” as the new territorial governor, William P. DuVal.3 Three years later, he won the first contested election for Delegate, becoming a non-voting member of the 19th U.S. Congress. He would hold onto this seat through five biennial elections, serving for a total of twelve years.

White wrote to his constituents that, on first entering office, he found the volume of business “almost sufficient to appal the stoutest heart….”4 He was Florida’s sole voice in Congress, representing a vast, uncharted region deficient in roads, ports, lighthouses, post offices, and all the other prerequisites of settlement and trade. Moreover, Florida’s development and emergence as a full-fledged state had to overcome two towering impediments: layers of conflicting land claims from its days as a Spanish and British possession, and an Indian population whose resistance to displacement would soon descend into open warfare. White had a key role in both of these struggles.5

On the major national issues of the day, Joseph White practiced a studied neutrality. For the lone representative of a territory “to mingle in the mighty conflict with the Representatives of sovereign States,” he believed, “would be resented as an intrusion by those on whose legislation they depend.”6 But the Delegate’s stance toward the administration, whether that of John Quincy Adams with which he was closely aligned or that of Andrew Jackson which replaced it, proved harder to conceal.

Facing a strong pro-Jackson opposition back in Florida, White tried to moderate his opinions of the “old Barbarian,” as he once privately dubbed the Hero of New Orleans.7 But his enmity toward the Jackson party was on open display, especially in quarrels with governors Richard Keith Call and William P. DuVal, which more than once came close to being settled on the dueling ground. Florida governors and other territorial officials received their appointments from Washington, and “the decayed, or neglected politicians of the States,” in White’s opinion, too often inherited these posts.8 The central government also saddled Florida with appointees having principles “odious” to his constituents, particularly on slavery, a system in which White with many politicians was much invested.9

Although Joseph White isn’t known to have ever set foot in the southern part of Florida,10 his faithful service to the territory, or at least to certain Florida interests, was familiar there, thanks in part to the lobbying of Key West proprietor and Washington resident John W. Simonton. Simonton and others had pressed for the establishment of a court at Key West equipped to handle claims arising from recurring shipwrecks in the Florida Strait.11 While White didn’t expressly favor creation of such a court, his supporters gave him credit for it, as he’d helped secure the appointment of its first judge by President Adams, and the judge’s reappointment by Jackson.12

Simonton was also a persistent advocate for expanding the Key West collection district north to Indian River, and extending to its port the cherished privilege of drawback, by which foreign goods could be admitted and customs duties refunded on reshipment.13 It’s not certain that Whitehead’s 1832 visit helped these measures along, but Joseph White saw that they were adopted soon after.14

White strove to cast local Florida concerns as issues of national interest, but with mixed success. In his first months as Delegate he pressed Congress to support the building of a ship canal crossing the peninsula from east to west. Besides dramatically shortening the distance between the ocean and ports on the Gulf–“more than a thousand miles of sailing would be saved,” he vowed–a canal would enable vessels to avoid the reefs, banks and shoals of the route around the cape, deemed “the most dangerous on the American coast.”15

But since commerce with the Caribbean remained vital, particularly to his southern constituencies, White proposed a second canal, or rather “three portions of canal” connecting bays and rivers along the Atlantic coast. A minimal amount of digging would open a “safe and commodious inland communication from St. Mary’s to Tortugas,” with easy access to Cuba, other ports on the Gulf of Mexico, “and whatever passage may be opened to the Pacific.”16

Congress voted an initial outlay of $20,000 for reconnaissance, which White considered a vindication of what his opponents must have thought the “glittering exhalation of a deluded mind….” Surveys were done, but no more progress was made on the westerly canal, and nothing further was heard of a southerly one before attention and money were diverted to the Second Seminole War.17

Whitehead had communicated with Joseph White, even before embarking on his long journey to Washington, about fisheries on the Gulf Coast upon which the Florida legislature threatened to impose a heavy tax. As collector of the customs Whitehead visited the fisheries in person, and came away convinced that there would be no economic gain from stripping law-abiding Spanish fishermen of their rights. The “ultimate object” of the act, wrote Whitehead, was clearly “to drive them from our shores,” which could only injure southern Florida’s own commercial well-being.18

Joseph White possessed a sympathy for Florida’s Spanish population that other politicians didn’t share, and a reputation for learning that would have appealed immediately to Whitehead. His competence in the language and the niceties of Spanish law brought him many signal victories in court over the party of his rivals, Call and DuVal.19 He produced a compilation of Spanish laws and ordinances gathered from European archives, which evolved into a standard text.20 Whitehead’s acquaintance with Joseph White gave him entrée to Washington’s cultural élite, as well as its political class.

On his second day in the capital, Whitehead delivered a letter to Congressman Richard Henry Wilde of Georgia, better known as a man of letters, then as now. Whitehead and Wilde proceeded to join Delegate White for dinner. Wilde and White were successful law partners and joint owners of a projected sugar cane plantation in the Florida panhandle, which White christened Casa Bianca. Former Kentucky governor John Adair, now in Congress, was also “of the party.” Whitehead didn’t record what was spoken of, but it was the presence of Adair’s daughter Ellen, the young wife of Joseph White, that rendered the gathering significant: “taste & fashion were shewn in her dress,” Whitehead observed, “and her manners and conversations were spirited & interesting.”21

Ellen Adair White must have captivated Washington society almost from the Whites’ arrival in the city. Josiah Quincy of Boston recalled that her name was “upon every tongue,–at least something like her name, for society had decreed that this fair woman should be known as Mrs. Florida White, her husband being a delegate from our most southern territory.”22

Younger than her husband by a generation, Ellen possessed beauty and charms so celebrated, and deployed them so skillfully, that she became a legendary figure out of all proportion to what can be decisively said about her.23 One observer recounted a social occasion during the Adams administration: how the crowd parted before her and her “numerous train of admirers–a dozen orange blossoms in her hair, the mild light of the gazelle in her dark eyes, and her bust cased in glittering silver….”24

It seems young William Whitehead was somewhat smitten, for a week after that dinner he called alone to pay his respects. Of her husband’s presence or absence on that occasion no mention is made, but Whitehead’s notes on the décor of Mrs. White’s parlor make plain that he was captivated by her person:

A splendid bust of Napoleon ornamented a side table executed by some Italian Master in a most beautiful manner and at one end of the apartment was a statue in plaster representing the “Venus of the bath” & a union of comfort, taste & fashion was apparent throughout, while at the same time luxury was not forgotten. It was a fit room for the display of the beauty & accomplishments of the gay Mrs Florida White.25

This recollection of Ellen White did not soon fade. Three years after making her acquaintance, Whitehead, now a newspaper editor and a married man, was pleased enough with an old British officer’s reminiscence of Mrs. White to reprint the passage in the Key West Enquirer. The description dwelled on her eyes, “her most striking feature”:

they were large, prominent, dark, and moved with a listless sweetness on the objects around her; but their momentary gaze would have to me been dangerous, had I met it before the chills of age and the vicissitudes of life had shrunk the veins, and diminished the pulses of a once too susceptible heart.26

Whitehead might well have come to understand the veteran colonel’s sentiments when, having himself endured “the chills of age,” he could still remember the “consideration and courtesy” he enjoyed in Washington from “Joseph M. White, delegate from Florida and his accomplished wife….”27

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.10.28

[1] The “public dinner” was announced and the program and other events of the day reported in successive issues of Key West’s weekly newspaper: Key West (Fla.) gazette 15 February 1832 2:2, 22 February 1832 2:2, 29 February 1832 1:4–2:1. The Gazette of 7 March 1832 1:1-3 recorded the toasts, which were reproduced in an appendix to Jefferson B. Browne, Key West, the old and the new (St. Augustine, Fla. 1912) 202.

[2] Walter C. Maloney, A sketch of the history of Key West, Florida … An address delivered at the dedication of the new city hall, July 4, 1876, at the request of the Common Council of the city (Newark 1876) 81.

[3] American & commercial daily advertiser (Baltimore, Md.) 18 July 1822 2:5. For details of White’s life and career, I rely principally on Ernest F. Dibble, Joseph Mills White: anti-Jacksonian Floridian (Cocoa, Fla. 2003; hereafter “Dibble, White”).

[4] Joseph M. White’s circular, to the people of Florida [Washington 1826] (hereafter “White, Circular [1826]”) 3, repr. in Noble E. Cunningham, Jr., ed. Circular letters of Congressmen to their constituents 1789–1829 (3 vols. Chapel Hill, N.C.; hereafter “Cunningham, Circular letters”) (3:1331-1340) 3:1331.

[5] For his promotion of Indian removal, see Dibble, White 69-85; for his record of success in land claims litigation, see ibid. 103-137, 173-181.

[6] Jos. M. White, “To the people of Florida,” Key West (Fla.) register, and commercial advertiser 9 April 1829 (2:1-5; hereafter “White, Circular [1829]”) 2:2; Cunningham, Circular letters (3:1528-1542) 3:1529. “When Florida shall have a place in the Union,” White wrote in concluding his first annual letter to his constituents, “should I then have the honour to represent you, she will fearlessly express her opinions on passing events, and honestly record her vote. Until then, it is wisdom in us, as it is in all men, to hold our peace, where we are not concerned, and minding our own business, let that of others alone.” White, Circular [1826] 12; Cunningham, Circular letters 3:1339-1340.

[7] Jos. M. White, Washington 8 May 1832 (not 18 May, as in Dibble, White 56 n.32), to Salmon P. Chase, Salmon P. Chase Papers: General Correspondence, 1830-1834, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. This letter was written after the unsuccessful effort to unseat Jackson by uniting the opposition behind former Attorney General William Wirt. A series of six anonymous letters to that end, published in a Baltimore newspaper and reprinted in a pamphlet entitled The presidency ([Baltimore? 1831]), may be traced to White. See Dibble, White 54-57.

[8] Jos. M. White, Washington 26 January 1830, to John C. Calhoun (?), in Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIV. The territory of Florida 1828-1834 (Washington 1959; hereafter “Territorial papers XXIV”) (333-337) 24:334. For extensive treatments of White’s feuds with leaders of the pro-Jackson party in Florida, see Herbert J. Doherty, Jr., Richard Keith Call, Southern Unionist (Gainesville, Fla. 1961) passim, Dibble, White 22-30, and James M. Denham, Florida founder William P. DuVal, frontier bon vivant (Columbia, S.C. 2015), esp. 176-209.

[9] For those enslaved on the Florida plantation that White co-owned with Richard H. Wilde, see Randy W. Burnett, “Florida bound: Casa Bianca plantation’s enslaved people,” Florida historical quarterly 98:2 (Fall 2019) 79-104. As the Whites spent months at a time in Washington or Europe, laborers on the plantation were managed by others. Although a proponent of expanding sugar production, an industry heavily reliant on enslaved labor, White in general opposed large plantations and speculation in public lands, advocating for squatters’ rights (preemption) and land purchases on a graduated scale that would favor Florida’s poorer white population. White brought enslaved people with him to Washington, including one Mariah, who in 1829 sued unsuccessfully for her freedom in District of Columbia Circuit Court. “Negro Maria v. Joseph M. White,” 3 Cranch, C.C. 663.

[10] White was urged to come to Key West in the wake of the disputed 1831 election: “a visit from you to this place, (your actual presence here), would do more to remove doubts, dissipate prejudices, & silence lying tongues, than all other means combined.” Henry S. Waterhouse, Key West 12 October 1831, to J. M. White, in Territorial papers XXIV (564-565) 565.

[11] Copies of a printed memorial “To the members of both houses of Congress” found at the Library of Congress and the American Antiquarian Society are signed by Simonton and dated 2 May 1826. The memorial was reprinted in Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIII. The territory of Florida 1824-1828 (Washington 1958) 560-565. Two years later, Simonton wrote that the remoteness from Key West of a court with admiralty jurisdiction left it “completely without the benefit of law”: J. W. Simonton, Washington 5 March 1828, to Philip P. Barbour, ibid. 1032-1034. Florida’s Legislative Council petitioned for such a court at Key West in resolutions of 1825 and 1827 found ibid. 379-380, 968.

[12] Concerning requests for an admiralty court at Key West, White wrote, “At one time, I thought favourably of it, and at another from the representations received, that it might be an impolitic measure. … This was a question in which the Territory, at large, had but little concern, and as it was of doubtful policy, I left it to those who felt an interest on both sides, after communicating all the information in my possession.” White, Circular [1826] 9; Cunningham, Circular letters 3:1337. In February 1828, he introduced James Webb to Adams, who in May appointed Webb judge for Florida’s Southern District: The diaries of John Quincy Adams: a digital collection, Massachusetts Historical Society, 37:448 (entry of 26 February 1828); Commission of James Webb as Judge (Southern District), in Territorial papers XXIV 10-11. White urged Jackson to reappoint him in a letter of 6 December 1831 and, although additional lobbying from Key West was deemed necessary, Jackson did so the following May: Daniel Feller et al., edd. The papers of Andrew Jackson, Volume IX, 1831 (Knoxville, Tenn. 2013) 912; J. W. Simonton, Key West 2 April 1832, to William T. Barry, and Commission of Judge Webb (Southern District), 17 May 1832, in Territorial papers XXIV 685-686 and 686 n.67, 700.

[13] J. W. Simonton, Washington 14 December 1829, to Jos. M. White, in Territorial papers XXIV 306-307. The drawback provision’s progress through Congress was followed in the Key West papers: see Key West register, and commercial advertiser 12 February 1829 2:2; Key West gazette 16 May 1832 2:1-2, 3:1; 4 July 1832 2:2-3; 11 July 1832 2:2.

[14] After declaring his intentions to run for a fifth term, White won effusive praise from Gazette editor Benjamin B. Strobel for these and other exertions “calculated greatly to advance our prosperity.” Some in the Keys had “warmly opposed” the Delegate (in the last election, he had lost the county by a vote of 70-17), but “in future,” Strobel predicted, “that opposition will cease: the people are beginning to know their true interests….” Key West gazette 4 May 1831 2:1; “Hon. Joseph M. White,” Key West gazette 23 May 1832 2:1; Key West gazette 18 July 1832 2:3; 22 August 1832 2:1. White’s support for (and from) Key West may have weakened with the separation of Dade from Monroe County and ongoing pressure to make Indian Key a port of entry: see Jacob Hausman, Indian Key (Fla.) 6 January 1834, to J. M. White, in Territorial papers XXIV 938-939; cf. W. A. Whitehead, Key West 24 November 1834, to J. M. White, in Charles Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXV. The territory of Florida 1834-1839 (Washington 1960) 67-68; James Webb, Washington 12 April 1836, to J. M. White, ibid. 273-274; “Division of Monroe County,” Key West (Fla.) inquirer 5 March 1836 2:2. Anti-White sentiment persisted, for in 1835 the Delegate was compelled to refute charges, “circulated to my prejudice at every election at Key West and Indian Key,” that he had denounced wreckers in Congress as “smugglers and pirates”: The enquirer (Key West, Fla.) 18 April 1835 3:2.

[15] J. M. White, Washington 20 November 1825, to James Barbour, Secretary of War, printed in Canal routes–Florida. Message from the President of the United States, transmitting a report and maps of a survey of canal routes through Florida. 23d Congress, 2d Session (H. Doc. No. 8, Serial Set 271), hereafter “Canal routes–Florida” (45-50) 46-47. In his 1829 circular White claimed to have pressed for a canal as early as 1824: White, Circular [1829] 2:2; Cunningham, Circular letters 3:1530.

[16] Jos. M. White, Washington December 1826, to Charles F. Mercer, printed in Canal routes–Florida (68-75) 71, and in Documents relating to the bill of the Senate, No. 1, “Supplementary to the act authorizing the Territory of Florida to open canals between Chipola river and St. Andrew’s bay, and from Matanzas to Halifax river, in said Territory,” approved March 2d. 22d Congress, 2d Session (S. Doc. No. 7) (37-44) 40.

[17] White, Circular [1829] 2:2; Cunningham, Circular letters 3:1531; cf. White, Dibble 34-39. Some in the pro-Jackson party alleged that White’s canal proposal had been allotted $20,000 “only for the purpose of keeping him in power.” R. K. Call, Tallahassee 8 November 1826, to Andrew Jackson, in Harold D. Moser et al., The papers of Andrew Jackson, Volume VI, 1825–1828 (Knoxville, Tenn. 2002) 232-233. Steps were taken in 1829 toward organizing a canal company on the Atlantic coast, but costs, miscommunications and politics seem to have caused both projects to languish. In 1831, Florida’s Legislative Council requested surveys of the two routes, the one along the coast “with a view to a Steam Boat navigation inland” from Charleston to Cuba. “Resolution by the Legislative Council,” January 1831, in Territorial papers XXIV 499-500. For other efforts to construct a canal across the peninsula see Charles E. Bennett, “Early history of the Cross-Florida Barge Canal,” Florida historical quarterly 45:2 (October 1966) 132-144.

[18] W. A. Whitehead, Key West 22 March 1832, to Joseph M. White, in Key West gazette 30 May 1832 2:1-2. See also the reports and petition presented to Congress by White in the weeks before Whitehead’s arrival, in Territorial papers XXIV 680-682, 681 n. 57, and my previous post 039–Fishermen’s friend.

[19] See George Graham, 18 June 1828, to President John Quincy Adams, in Territorial papers XXIV 26-27, and Dibble, White 173-181.

[20] The compilation was first printed, after some delay, in 1829: see Territorial papers XXIV 168 n.71, 177, 203, 354. According to White’s introduction to the 1839 revision, the original was “three times published by the government of the United States….” Joseph M. White, A new collection of laws, charters and local ordinances of the governments of Great Britain, France and Spain, relating to the concessions of land in their respective colonies; together with the laws of Mexico and Texas on the same subject. To which is prefixed Judge Johnson’s translation of Azo and Manuel’s Institutes of the civil law of Spain (2 vols. Philadelphia 1839). White’s “Sketches, historical, political and topographical of Louisiana and East and West Florida” seem to have been less fortunate. Perhaps intended as an elaboration of James Grant Forbes’s 1821 Sketches, historical and topographical, of the Floridas; more particularly of East Florida, they were expected to be “put to press in London” sometime in 1835, but apparently never saw daylight. “History of Florida,” The enquirer 14 March 1835 3:1; “Americans in Paris,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 26 August 1835 2:3; The enquirer 12 September 1835 3:3.

[21] W. A. W[whitehead], Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement, vol. 2nd, Key West (Fla.) Art & Historical Society (hereafter “Whitehead, Memorandums”), entry of 26 April 1832. For the Casa Bianca plantation cf. Dibble, White 49-54, and see above, note 9.

[22] Josiah Quincy, Figures of the past from the leaves of old journals (Boston 1888) 268. That Ellen adopted or was given the name “Florida” during Joseph White’s years in Washington is doubtful. The sobriquet was almost certainly his, “to distinguish him from another White in Congress,” and only much later transferred to her. Edward L. Tucker, Richard Henry Wilde. His life and selected poems (Athens, Ga. 1966) 22. The shift may have originated in articles by Mary Edwards Bryan: “Three dainty poems,” The sunny South 9:437 (9 February 1884) 4:4; “Florida White,” The sunny South 10:471 (4 October 1884) 5:1-2, 10:472 (11 October 1884) 5:2-4. The latter was reprinted in James Barnett Adair, comp. Adair history and genealogy (Los Angeles 1924) 78-87. Cf. A. J. Hanna, A prince in their midst. The adventurous life of Achille Murat on the American frontier (Norman, Okla. 1946) 219; Margaret Anderson Uhler, “‘Florida White,’ Southern belle,” Florida historical quarterly 55:3 (January 1977) 299-309 (hereafter “Uhler, ‘“Florida White”’.”) John W. Simonton of Key West and Washington did have a daughter named Florida; she was born in 1830.

[23] Dibble, White 139-157 engages in a critical review of the numerous legends surrounding Mrs. “Florida” White, many emerging only after the Civil War. What role Ellen White may have had in this mythmaking remains an unsettled question, but Margaret Uhler’s appraisal seems not without foundation: Ellen “was magnanimous and petty, democratic and haughty, ingenuous and artful. But no one who entered the orbit of this captivating personality ever forgot her.” Uhler, “‘Florida White,’” 309.

[24] Mrs. E. F. (Elizabeth Fries) Ellet, The court circles of the Republic, or the beauties and celebrities of the nation; illustrating life and society under eighteen presidents; describing the social features of the successive administrations from Washington to Grant; … (Hartford, Conn. 1869) 137. For later public appearances by Mrs. White, see ibid. 171, 328-329.

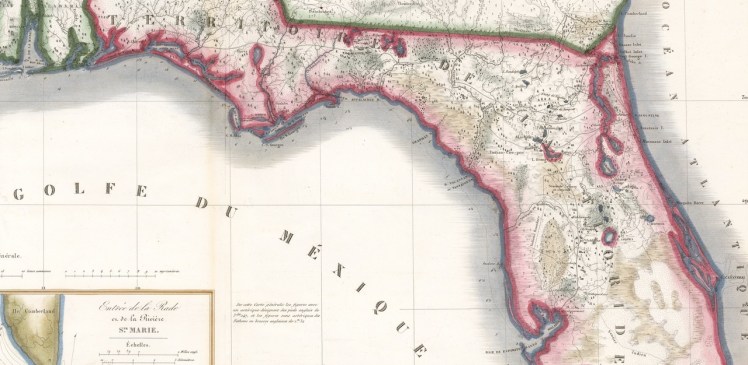

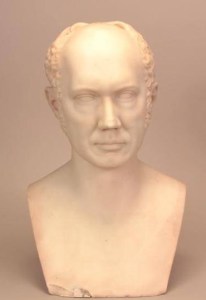

[25] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 2 May 1832. The sculptures may have been souvenirs of one of the Whites’ European tours. It has been thought that Ellen sat for Horatio Greenough’s bust of her (seen here) during a stay in Florence in 1833, and that Greenough finished the bust of Joseph (seen above) two years later. See Nathalia Wright, Horatio Greenough. The first American sculptor (Philadelphia 1963) 100-102; eadem, ed. Letters of Horatio Greenough, American sculptor (Madison, Wis. 1972) 188-189 n.7.

[26] The enquirer 18 April 1835 3:1-2, from “Journal of a veteran officer,” New-York (N.Y.) mirror, a weekly journal, devoted to literature and the fine arts 12:36 (7 March 1835) 284. See “Corrections,” The enquirer 25 April 1835 3:1. Excerpts from “Journal of a veteran officer” were published serially in the weekly New York Mirror beginning 31 January 1835. I have not yet succeeded in identifying their author, one “Colonel McKenzie.”

[27] Typewritten transcription of an unpublished memoir, under the title “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” of which copies are held by the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Page 33 contains the reference.