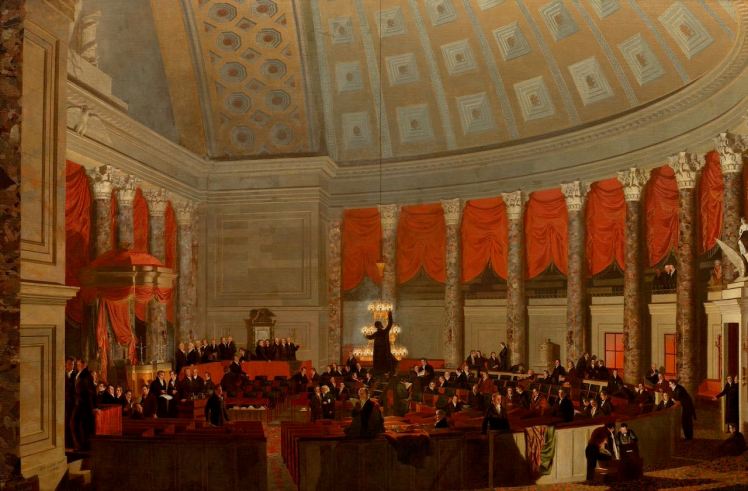

BEHIND the Speaker’s chair and around the perimeter of the Hall rose smooth columns of pudding stone, looking to some observers almost good enough to eat. Festoons of crimson tapestry between them lent an air of luxury to the space.1

An intent observer of the House’s deliberations might pay little heed to such embellishments, but in the chamber’s vastness and beneath its soaring half-dome, speeches and rulings had to overcome “every accidental noise and separate conversation” in order to be heard. Sounds were so muddled by the reverberations that legislators might well lose track of the words they themselves had spoken.2

The acoustic defects of the Hall of Representatives were a cause of complaint from when it first opened in the Capitol’s south wing in 1807. Neither rebuilding after the British burned Washington nor successive reports or recommendations could furnish a remedy. The House finally escaped this evil by moving, in 1857, to an entirely new chamber. The old Hall was repurposed as the museum of statuary that it is today.

The echoes, while a serious inconvenience, didn’t altogether prevent the House from doing its work, nor did they discourage the occasional flight of oratory or descent into riveting melodrama. It was an episode of the latter variety that filled the House galleries during much of William A. Whitehead’s first sojourn in the federal city.

By 1832, American politics had turned highly factious, the battle lines between President Andrew Jackson’s party and the anti-Jacksonians sharply drawn. Nor was Washington yet so far from the frontier as to be safe from the code that made a virtue of vengeance, and turned aggressive words readily into deeds. There was outrage, but scant surprise, when a brief allusion made on the House floor led to one man’s vicious caning of another on Pennsylvania Avenue.

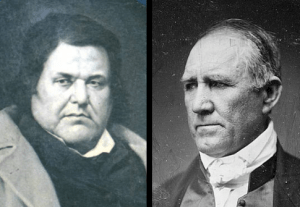

The offending words belonged to William Stanbery, a transplanted New Jerseyan representing Ohio’s eighth district. To William Whitehead, Stanbery looked “morose in the expression of his countenance”; the coarse hair on his large head, “standing almost erect, gave him quite a rough appearance.”

In a speech some weeks earlier, the Ohio representative had made reference to an alleged attempt to defraud the government, incidentally implicating Sam Houston, a Jackson ally and former Tennessee Congressman and governor.3 Houston was not present to hear himself mentioned, but reading the speech in the National Intelligencer he took umbrage, and sent Stanbery a note demanding to know if the words were his. Houston’s ultimatum and Stanbery’s refusal to acknowledge it were, by protocol, necessary steps preceding a challenge to a duel.

When the two men came face to face, however, it was at night, and seemingly by accident. With a hickory walking stick made from a tree at Jackson’s Hermitage, Houston rained blows on Stanbery’s head, then tackled him as he tried to get away. In the midst of the struggle Stanbery, fearing for his life, drew a pistol that apparently failed to fire. Houston intensified the attack, leaving his foe at last “severely bruised and wounded,” as the victim wrote the next morning in a communication to his colleagues, “by reason of which I am confined to my bed, and unable to discharge my duties in the House, and attend the interests of my constituents.”4

Within a week, the House Sergeant at Arms had placed Houston under arrest. He would be tried by the body to which he had once belonged, with Francis Scott Key, author of “The Star Spangled Banner,” beside him as counsel. Houston, however, took command of his own defense and, at the conclusion of the trial on 7 May, delivered a stunning peroration.5

Stanbery’s friends in Congress maintained that the accused had violated Congressional privilege, jeopardizing the liberty and even the safety of legislators. But Houston turned this argument on its ear: “All history will show,” he thundered, drawing illustrations from ancient Greece and Rome, Cromwellian England and Revolutionary France, “that no tyrant ever grasped the reins of power till they were put into his hands by corrupt and obsequious legislative bodies.”6

In fact, Congressional immunity was on trial along with Sam Houston: could the people’s representatives be taken to task for remarks made in the course of debate? Even the pro-Jackson newspaper in Whitehead’s current hometown, the Key West Gazette, warned of the consequences of an acquittal:

Shall a representative of the people, for a free and honest expression of his opinions as such, be assailed and beaten by every bully who may be offended thereat? If so, “club law” will soon be the paramount law of the land–and farewell to our liberties.7

But it’s the entertaining nature of the proceedings that prevails in the comments of 22-year old Whitehead. The figure of the defendant impressed him: Houston was “stout” (though less so than his opponent) and a “genteel, and good looking man,” who sat at a small desk provided for him, jotting occasional notes of the witnesses’ testimony, and “apparently very much at ease….”

The injured Stanbery came off far less well: “It could hardly be thought,” Whitehead reflected, “that he had but a few days before been so severely handled by one apparently so near his own weight.” Furthermore, by questioning the truthfulness of a Missouri senator’s eyewitness account, Stanbery placed himself “in rather a ridiculous situation,” and was forced to recant, ascribing his remarks to “the excited state of his feelings at the time.”

Although the House convicted him by a vote of 106-89, Houston was let go with a mere reprimand. Stanbery secured a conviction in federal court for assault and battery, but the penalty, a $500 fine and court costs, was eventually remitted by the president. A House inquiry that Stanbery demanded found the initial insinuation of fraud to be without merit. Sam Houston, his public image much burnished by the affair, went on to lead the war to wrest Texas from Mexico, head the Texan republic as its first president, and represent it in the U.S. Senate when it became a state.

Whitehead, of course, had not come to Washington to be a mere spectator. His patron John W. Simonton, whose family resided in the capital and who enjoyed a host of friendships and contacts in government, including the president, doubtless sponsored the trip as a means to advance the commercial interests of Key West. But Whitehead’s position as collector of federal revenue didn’t guarantee easy access to the halls of power: calling hours were limited and the hours of waiting could be long.8

Simonton, and probably others, had therefore armed him with letters of introduction to “no less than twenty” members of Congress and two or three heads of executive departments. In making the rounds, Whitehead was introduced to other figures of importance, becoming in his words “quite well known … for one of my age and attainments,” and by his own account helped pending legislation to become law.9

On Whitehead’s second day at the Capitol, New Jersey’s Mahlon Dickerson introduced him on the floor of the Senate. The chamber differed little in its ornament from that of the House, but as a body the Senate was only a quarter as large, its proceedings were more decorous, and its hall “well adapted to speaking as every word uttered is audible in any part.”10 Leaning forward from one of the sofas provided for guests allowed onto the floor, Whitehead could glance excitedly from one to another of “the greatest men of the country assembled together … and compare the expression of their countenances and the peculiarities in the appearance of each.”11

As president of the Senate, South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun occupied the most conspicuous seat, although from his iconography one would believe him “a much larger man than he really is. Heavy eye brows and eyes deep set” (which an engraved portrait Whitehead preserved of him quite failed to convey) “give a particularly penetrating character to his countenance….”12

Calhoun had presided in this very chamber over an occasion more sensational even than the trial of Sam Houston, and a good deal more consequential: the January 1830 debate between two of the Senate’s finest orators, Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts. Hayne’s spirited defenses of state sovereignty and Webster’s memorable pronouncements on the primacy of the national union had laid bare the country’s sectional divide. Few with any sense could look to the future without trepidation.

Whitehead had availed himself before this of opportunities to observe Webster. While his hopes of hearing the great defender of the Union were disappointed, the letters he carried for Hayne enabled him to meet as well as study “the talented champion of the South….” Doubting his ability to give “a true idea of the man,” Whitehead nonetheless delineated his handsome features in considerable detail, betraying an attraction felt in common with many of his era.13

Finding the Senate in closed session one day, Whitehead proceeded through the Rotunda to watch the proceedings at the other end of the Capitol. After some private business was disposed of, the House turned to a committee report on the contentious subject of the Bank of the United States.14 Among the committee members who rose to comment pro or contra, John Quincy Adams ventured only to say, with a tinge of irony, that not having “heard or read the whole of it” he would not take responsibility for the report’s contents.15

Sworn in to his seat the previous December at the age of 64, Adams was the oldest freshman member of the Twenty-second Congress. Although Andrew Jackson had ousted him from the White House two years earlier, making him a one-term president like his father, his Massachusetts constituents sent Adams back to Washington as a member of the House. Whitehead saw his return to public service as “a beautiful instance of the republican nature of our institutions. … His remarks, from the elevated rank he holds among our statesmen, are always attended to with interest; which cannot be said of every member of the Body.”16

A veteran of an era at least superficially more civil, Adams knew to expect little deference from his younger fellows, and was to be a thorn in the sides of many of them. Indeed, over the next sixteen years of his service in Congress, ending only with his death, Adams was exalted and berated, and even subject to threats on his life, for skillful attacks on the Jacksonian policy of Indian removal, the disastrous war with the Seminoles in Florida, the pressure to annex Texas, and the slaveholders’ unrelenting grip on government. His insistence that petitions for an end to slavery in the District of Columbia, and indeed for abolition nationally, be read and recorded were to make him at once the nation’s most respected and most reviled champion of freedom of speech, and of the right of petition.

William Whitehead’s attention centered once more on the physiognomy of his subject. “Nothing can be finer than the bare marble brow of Mr A.,” he wrote, “and as the light falls upon its polished surface it gives to the expression of his countenance a very fine effect;–such as I do not recollect ever witnessing before.”17 The conscience of the Congress was a mantle that, in 1832, the venerable Adams had only begun to assume, but Whitehead’s youthful eyes may have caught a glimmer of that future.

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.05.12

[1] According to William A. Whitehead, “a Gentleman in Washington” once commented that the columns “make a man about 5 Oclock feel exceedingly hungry from the resemblance there is in their texture to that of an old fashioned head cheese.” This and other recollections of Whitehead’s visit to the city are preserved in his Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement, vol. 2nd (hereafter “Whitehead, Memorandums”), a manuscript held by the Key West Art & Historical Society. The entry for 25 April 1832 contains his descriptions of the Capitol building and the House and Senate chambers.

[2] “This defect was foreseen,” wrote architect Benjamin Latrobe in 1808, and made “debate very laborious to the speaker and almost useless to the hearers.” See “Report of the Surveyor of the Public Buildings of the United States at Washington, March 23, 1808,” in The debates and proceedings in the Congress of the United States; with an appendix, containing important state papers and public documents, and all the laws of a public nature; with a copious index. Tenth Congress–First Session. Comprising the period from October 26, 1807, to April 25, 1808, inclusive (Washington 1852) (coll. 2749-2760) col. 2752. Of the Hall of Representatives Whitehead wrote: “Its dimensions are so great and its dome (& probably its pillars likewise) causes such a reverberation of sound that it is with great difficulty the members can at all times make themselves understood in every part of it.”

[3] Stanbery made the comments on 31 March, in the course of debate on the questionable dismissal of a Maine customs inspector. See Register of debates in Congress, comprising the leading debates and incidents of the First Session of the Twenty-second Congress … (hereafter “Register of debates in Congress”), vol. 8, pt. 2 (Washington 1833), coll. 2321-2322; “McClintock versus McCrate,” Niles’ weekly register, ser. 4, 6:7 (14 April 1832) 114-115.

[4] William Stanberry, 14 April 1832, to Andrew Stevenson, Speaker of the House, in Register of debates in Congress, vol. 8, pt. 2, col. 2512.

[5] Houston’s trial in the House began on 18 April and concluded on 14 May. The record is found in Register of debates in Congress, vol. 8, pt. 2, coll. 2562-2912, pt. 3, coll. 2913-3022; cf. Niles’ weekly register, ser. 4, 6:8 (21 April 1832) 133-134; 6:9 (28 April 1832) 153, 156-163, 171-176; 6:10 (5 May 1832) 177-181; 6:11 (12 May 1832) 208; 6:12 (19 May 1832) 219-222. For brief accounts of the attack, trial and aftermath see Marquis James, The raven. A biography of Sam Houston (Indianapolis 1929) 162-173; Roger M. Busfield, Jr., “The Hermitage walking stick. First challenge to Congressional immunity,” Tennessee historical quarterly 21:2 (June 1962) 122-130; James L. Haley, Sam Houston (Norman, Okla. 2002) 81-86. Whitehead related his impressions of the trial, which he watched first-hand on 25 and 26 April. He may have seen more of the proceedings after 2 May, but what we have of the Memorandums ends on that date.

[6] Register of debates in Congress, vol. 8, pt. 2, col. 2817.

[7] Key West (Fla.) gazette 23 May 1832 2:1. Reporting on the conclusion of Houston’s trial and a similar assault on another member of the House, the Gazette offered a reworking of Hamlet: “Some must laugh, while others weep–So runs the world away.”

[8] “Washington is not a place where etiquette (so far as hours are concerned) has much place–calls upon members of Congress are made before 10 O’Clock. The President is waited upon from 10 to 12 and the Heads of Departments from 10 to 3, and oftentimes you may have to wait 3 out of those 5 hours before you obtain an entrance.” Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 27 April 1832.

[9] Transcription of an unpublished memoir, under the title “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” of which copies are held by the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Page 33 contains the reference. Whitehead lobbied Representative Henry G. Lamar of Georgia and Senator Nathaniel Silsbee of Massachusetts, who sat on the Commerce committees of their respective chambers, to obtain the lucrative right of drawback for the Key West customs district. Until Whitehead’s visit Silsbee had been opposed, “but explanations which I was enabled to give him removed the false impressions he had in relation to the subject and his influence for us may be expected.” Whitehead, Memorandums, entries of 27 April and 1 May 1832.

[10] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 25 April 1832.

[11] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 27 April 1832.

[12] Whitehead illustrated his journal with a number of engravings, including plans of the city of Washington and the Capitol, and images of the sitting President, Vice President, Secretary of State and Postmaster General. The portrait of Vice President Calhoun is apparently not found in the manuscript.

[13] “Mr H. has a remarkable youthful appearance. He might be thought to have attained the age of 36 or 7 – though probably 4 or 5 years older. [Whitehead was not far off: Hayne had turned 40 the previous fall.] … He is about the middling stature and rather slightly made, his hair light, with here & there a lock rather lighter than the others, and he wears it combed smoothly off his forehead ‘school-boy fashion.’ His eyes are grey or very light blue: his mouth full and when conversing or speaking in the Senate chamber is ornamented with a smile that animates and enlivens his whole countenance. I never knew a person who spoke in public with so much spirit & yet with apparently so little labour as Mr Hayne–with much gesture and his body in constant motion his words flow in a constant strain of eloquence–no faltering nor any vain attempts at effect.” Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 29 April 1832. Robert Y. Hayne had introduced legislation in the Senate at the end of February to extend the right of debenture to Key West; it was similar to a bill already under consideration by the House. Hayne was thought to be “very friendly to the measure,” and it became law that July. See Key West gazette 4 July 1832 2:2, 11 July 1832 2:2.

[14] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 30 April 1832.

[15] Register of debates in Congress, vol. 8, pt. 2, col. 2662.

[16] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 30 April 1832.

[17] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 30 April 1832.