WHEN retained at age 18 to produce a survey of Key West, whose existing streets he could count on the fingers of one hand, William A. Whitehead drew a town “more pretentious on the map than in reality.”1 He would have been unfazed, then, to discover that most streets and squares on a “Plan of the City of Washington”–Pierre L’Enfant’s grand design, as rendered in print by Andrew Ellicott–yet had only a hypothetical existence.2

While the 1814 British invasion of Washington was devastating, the highly symbolic burning of the Capitol and White House had renewed American determination to keep the federal city there, and to build and rebuild it as planned. But economic crises and labor shortages had conspired to make its growth in the intervening years fitful at best.

Arriving in April 1832, Whitehead found a city “most elegantly laid out” and the view from the hill of the Capitol “most beautiful,” if still predominantly pastoral. The prospect would be less pleasing, he guessed, “when the City shall have increased in size and become compactly built.” Pennsylvania Avenue, that “great thorough fare” of Washington, and of all its diagonal boulevards “the most thickly built upon,” remained an unimproved dirt road in 1832, muddy in wet weather, dusty in dry.3

On his printed “Plan” only the two most prominent public buildings were named, the Capitol and the Executive Mansion (called the “President’s House” after L’Enfant’s original), so on one side of it Whitehead named others and added a key. He designated the General Post Office and Patent Office with the letter A; Judiciary Square and City Hall became B; and the headquarters of the War, State, Navy and Treasury departments, which stood at the four corners of the White House grounds, he marked C to F, first sketching in the outlines of those departments whose offices were not yet built in Ellicott’s day.

Whitehead also labeled three extensive areas that the Plan did not identify. Along the Anacostia River or “Eastern Branch,” he indicated the Navy Yard and Marine Hospital grounds, and over the vast public gardens that L’Enfant had projected westward from the foot of Capitol Hill he penned the single word “Mall,” a name unofficially employed soon after the national government moved here in 1800.

Whitehead’s small copy of the Ellicott Plan, one of many versions engraved abroad using American prototypes, is folded and pasted with other prints and sketches into a handwritten journal of his travels, playfully entitled Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement.4 “Sixteen Days in Washington,” the record of Whitehead’s visit to the federal city, fills the last thirty pages of its second volume, but it is incomplete. The narrative would have carried over into a third volume which, like the first, remains undiscovered.

Whitehead’s account begins at the Capitol, the city’s hub and the center of Ellicott’s Plan. Spreading outward from here is a rectilinear grid of streets, called “(those running North & South) after the letters of the alphabet and (those running east and west) according to number….” These thoroughfares were not labeled on the Plan, and on the ground most had little human activity to distinguish them. The Capitol was a point of origin, but also a place to which Whitehead had many occasions to return.

One of his first calls was to Mahlon Dickerson, an influential senator from Whitehead’s native state.5 Born into New Jersey’s landed gentry, Dickerson had come up a devoted Jeffersonian, and now backed the administration of Andrew Jackson. He also nurtured hopes of becoming Jackson’s next vice president, although the commander in chief would pass him over and, in two years’ time, appoint him Navy secretary instead. An attorney, industrialist and bibliophile, Dickerson as long-serving chairman of the joint Library Committee won praise for the “indefatigable exertions and literary taste” with which he built up the Congressional library’s collections.6

Whitehead’s introduction to the Library of Congress came not at Dickerson’s hands but through Richard H. Wilde, a Georgia representative and sometime man of letters. The windows of the library, then situated behind the Capitol’s west portico, afforded sweeping views of Pennsylvania Avenue and the Mall. But its glory resided in its books, a uniting of Thomas Jefferson’s own volumes, which replaced the original collection lost in the inferno of 1814, with thousands more added since then, all thematically organized in ten alcoves. Whitehead especially marveled at the sumptuous, hand-colored images in Audubon’s monumental Birds of America, only a quarter of which had been issued to date. More recent studies by the famed ornithologist and painter, then on an exploratory journey in the Florida Keys, hadn’t yet found their way into print; yet Whitehead judged the available folios as “exceeding in execution any thing before published.”7

As his rounds led away from the Capitol to other arms of government, Whitehead found the city’s design somewhat an impediment to efficiency. “The first thing a stranger discovers at Washington,” he noted, “is the great distance of the public buildings from each other, particularly if his business requires his attendance at many of them in the course of the same morning.”8 He had calls to make on at least three of the executive departments, which tended to have many more petitioners than hours in a day.9

As customs collector and superintendent of lights for Florida’s southern shores, Whitehead was obliged to call at the department overseeing those functions. The offices of the Treasury received and corrected his monthly and quarterly accounts and authorized his expenses, but for the first sixteen months of his tenure he’d had no first-hand knowledge of their inner workings.

While the Treasury building, reconstructed after its torching by the British, closely resembled the earlier one in style and size, the volume of work carried on inside had grown exponentially. Letters and reports that poured in from custom houses nationwide were piled high on crowded wooden desks, or stuffed unceremoniously into cubbyholes. Shelves groaned beneath the weight of massive ledgers, which even littered windowsills and floors.

Yet Whitehead took no apparent notice of the cramped and filthy quarters derided just a few years earlier by the acerbic journalist Mrs. Anne Royall.10 Conditions could not have changed much, but it would have been impolitic of Whitehead to comment on disarray in a department that employed him. At least he could be assured that affairs at Key West were in order. When another of Royall’s complaints, the inadequate protection against fire, soon proved well-founded (this time from the act of a lone arsonist) Whitehead was able to supply the Treasury with copies of correspondence it had lost. He could do little for the Post Office and Patent Office, whose building suffered a worse conflagration three years later.

Tactfully, the Memorandums breathe barely a hint of a scandal the government had only started to put behind it. A slowly widening breach, instigated by the social exclusion of the War secretary’s wife, had in the previous year forced the resignation and replacement of almost every member of the Cabinet. This rupture caused havoc in Jackson’s White House; it permanently alienated him from his vice president and led to some dramatic scenes, not the least being the flight from the city of his first Treasury secretary, for fear of assassination.

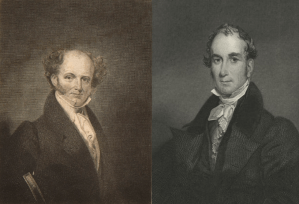

The affair was surely too awkward for Whitehead to venture any allusion to it. He merely stated–a fact already well-known–that a new running mate would join the president in that fall’s election. And he inserted a likeness (“a good one too”) of the probable nominee: not the studious and stalwart Mahlon Dickerson of New Jersey, but the savvy ex-Secretary of State from New York, Martin Van Buren.11

After the great Cabinet purge, the Treasury job went to Louis McLane, Jackson’s late minister to Great Britain. In his former position McLane had negotiated the reopening of the British West Indies to American merchant ships, an agreement that augured well for commerce, even at the diminutive port of Key West.

How much this achievement would affect Whitehead’s business at the custom house remained to be seen. He judged the breakthrough a testament to his new chief’s abilities, but this was an opinion he had no opportunity to verify. On his first attempt to see McLane, he was rebuffed: the secretary, preoccupied with a report on manufacturing to be delivered to Congress the following day, “was ‘not at home’ to those who called.” Later in his stay Whitehead gained “a moments audience” in which to glimpse the man’s “intellectual countenance,” although he would afterwards reflect that “perhaps I fancied I saw the mind which I knew him to possess.”12

Despite the upending of the Cabinet and Andrew Jackson’s passion for “retrenchment and reform,” the vast majority of government employees remained in place. The leading career officer of the Treasury was Joseph Anderson, its First Comptroller. When Whitehead met “old Judge Anderson” he was old indeed: a veteran of the Continental Army, he had served the department so long “that he is almost looked to as the Father of the establishment.” Whitehead relished good conversation, and Anderson was “fond of talking” while other officials seemed to have little time for it. Talk for talk’s sake, however, little impressed Whitehead’s interlocutor: when he was a member of the Senate some twenty years ago, Anderson recalled that “less was said and more done,” but “now every man thought it his duty, apparently, to say as much and do as little as possible.”13

Levi Woodbury was the new Cabinet’s Navy secretary (in a later reshuffling he would take McLane’s place at Treasury), and in a brief conversation Whitehead pitched to him the advantages of selecting Key West, “our little sea-girt Isle, for a naval station.”14 The record fails to show whether he had occasion to press those advantages further, or to raise the less congenial claims of the island’s proprietors (chiefly of his own brother, John Whitehead) for damages sustained under the naval occupation of the 1820s.15

William T. Barry, the Postmaster General, is the only other department chief we know Whitehead called upon. This amiable gentleman, who received him “very politely,” seemed to manage the post office, “the labours of which are enormous, with great ability.”16 Later historians do not share this impression of Barry, the only member of the old Cabinet to keep his position in the new one: nothing recommended him, apparently, but his complete loyalty to the president.17

The glowing orb around which these satellites revolved–and with which they sometimes collided–was Andrew Jackson, now 65 years old and in the fourth year of an administration that, however much injured by division, scandal, his own physical debility and profound personal loss, looked politically invincible. The man possessed a sagacity and vitality remarkable for his age and condition, which seldom failed to impress intimates and outsiders alike.

At a short audience with the president, Senator Dickerson by his side, the 22-year-old Whitehead felt “gratified with the pleasing manners and plain address of the ‘old Hero’–and somewhat surprised at the energy with which he conversed.” When the three men’s discussion turned for a moment to the vexed issue of customs duties, the president observed that, “were he not an inhabitant of Washington with the subject constantly brought to his notice,” such matters “would hardly receive from him a moments attention,” as nearly all he wore and consumed was American-made. To make this point, Jackson indicated a magnificent saddle on display in his office: a recent gift from an admiring Irish-born manufacturer of Albany, New York, it showed “the excellence of the workmanship of our Mechanics.”18

Whitehead’s first interview with Jackson was brief, but before leaving the President’s House he spent “an hour or two very pleasantly” in its library. He hoped to find some “Historical memoranda” pertaining to the settlement of Perth Amboy, the site of his parents’ New Jersey home and, until he left to take charge of the Key West customs, also his own. Whitehead looked forward to passing the coming months in that familiar corner of East Jersey (he would not resume his Florida residence until October), and this short spell of research at the White House, fruitful or not, is an early instance of a vibrant interest in Amboy history that would endure to the end of his life.

A letter of introduction left for Andrew J. Donelson, Jackson’s nephew and private secretary, prompted an invitation to return and dine with the president. Jackson is known to have kept a fine table, and it’s unfortunate that little more of the event is recorded than Whitehead’s later recollection of the “old Hero”: his manners, his conversation and his clay pipe.19

The final few days of April 1832 were cloudy, rainy and cool, giving rise to “a general complaint … of the backwardness of the Spring.” But as if on cue the month of May dawned sunny, the air warmed and freshened, and the earth teemed with life. Whitehead attended a fashionable ball in the evening, one of at least three May Day soirées bringing the daughters of Washington society out to meet their admirers. It almost seemed he had crossed into a “fairy land,” he thought, as a bevy of flower-bedecked young ladies flitted seraph-like about him. Pleading a limited acquaintance with “Washington Belles,” however, he “danced only two sets.”20

What else transpired or was achieved in the last seven of his “Sixteen Days” Whitehead consigned to the missing third volume of the Memorandums. He had come to Washington with more than twenty letters of introduction and a full agenda. The length of his stay assures us of his perseverance, even if, on leaving the unfinished capital, parts of his mission had likewise to be left unfinished. After all, there’s not the least doubt of his eagerness to reach Perth Amboy, a place of “peculiar attractions,” and not all of them historical.21

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.11.08

[1] Jefferson B. Browne, Key West, the old and the new (St. Augustine, Fla. 1912) 11. On Whitehead’s 1829 survey and map of Key West, see my earlier posts 014–The measure of the island and 016–A key of many colors.

[2] The imprint on Whitehead’s copy of “Plan of the City of Washington” reads: “Published by J. Stockdale Piccadilly 16th. Sepr. 1798.” This second state of Stockdale’s 1794 engraving was prepared for Isaac Weld, Travels through the states of North America and the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (2 vols. London 17992), plate facing 1:81. Whitehead pasted the engraving into Memorandums of peregrinations by land & water recorded for my own amusement, vol. 2nd, from July 1830 to May 1832, by W. A. W. (hereafter “Whitehead, Memorandums”), a manuscript in the keeping of the Key West Art & Historical Society. The map is featured at Whitehead’s entry for 25 April 1832. For this version of the Ellicott plan, see Coolie Verner, “Surveying and mapping the new federal city. The first printed maps of Washington, D.C.,” Imago mundi 23 (1969) (59-72) 72 (no. 14).

[3] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 25 April 1832. The macadamizing of Pennsylvania Avenue began later that year: Gaillard Hunt, ed., Forty years of Washington society portrayed by the family letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (Margaret Bayard) from the collection of her grandson J. Henley Smith (New York and London 1906) 335.

[4] Whitehead’s title may have been inspired by a century-old work associated with artist William Hogarth: see my earlier post 069–Road trip, note 1.

[5] Whitehead had a letter of introduction to Dickerson, and is sparing in his description of the senator, calling him simply “a plain old gentleman”; Dickerson would introduce Whitehead on the floor of the Senate the following day, and take him to meet the president the day after. Whitehead, Memorandums, entries of 26, 27 and 28 April 1832.

[6] “District of Columbia.–Concluded,” Daily national journal (Washington, D.C.) 11 April 1827 2:2.

[7] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 27 April 1832.

[8] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 26 April 1832.

[9] “Washington is not a place where etiquette (so far as hours are concerned) has much place–calls upon members of Congress are made before 10 O’Clock. The President is waited upon from 10 to 12 and the Heads of Departments from 10 to 3, and oftentimes you may have to wait 3 out of those 5 hours before you obtain an entrance.” Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 27 April 1832.

[10] Anne Royall, The black book; or, a continuation of travels, in the United States (3 vols. Washington 1828-29) 3:150-151, 157.

[11] During his first call on President Jackson, Whitehead noted the placement of Van Buren’s portrait at the White House: “The apartment was ornamented with many handsome paintings including several portraits of distinguished men, among others that of Mr Van Buren was not the least conspicuous from its situation and the truth of its likeness.” Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 28 April 1832. A visit to Saratoga, New York, in August 1830 led to a closer encounter with Van Buren, who was staying in the same hotel as Whitehead and his party. Whitehead, Memorandums 32.

[12] Whitehead, Memorandums, entries of 26 and 30 April 1832. On 27 April, Whitehead wrote McLane concerning the wages of a boatman hired by an inspector at the Cape Florida light; McLane only replied to this letter on 8 May. Another letter of Whitehead’s dated 9 May, shortly before he left Washington, reveals the substance of their conversation: whether the one that took place on 30 April or a later one is uncertain. He had brought up the inadequate pay allowed for care of sick and disabled seamen, and the lack of stable lodging for them at Key West. McLane wrote in response to Whitehead’s first request that the Marine Hospital fund could not currently be increased, and rates would therefore remain the same. Louis McLane, Treasury Department 8 May 1832, to Wm. A. Whitehead; W. A. Whitehead, Washington 9 May 1832, to Louis McLane; Louis McLane, Treasury Department 10 May 1832, to W. A. Whitehead; all in “Letters to and from the Collector, Key West, Dec. 13, 1826 to Mar. 29, 1833,” Correspondence of the Secretary of the Treasury with Collectors of Customs, 1789–1833. Record Group 56, General Records of the Department of the Treasury, National Archives and Records Administration, Microcopy 178, Roll 38 (Washington 1956), pages 79, 114 and 78.

[13] Whitehead, Memorandums, entries of 26 April and 2 May 1832. On the former date, Whitehead paid his “respects” to Joseph Anderson, and on the latter “passed a half hour with him very agreeably.” He mentions no letter of introduction, which suggests that none was necessary; perhaps the Comptroller’s position didn’t warrant it, but it’s also possible the men were already acquainted.

[14] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 30 April 1832.

[15] Late in life, Whitehead recalled that one of his objectives in Washington had been to examine “some records containing matters calculated, it was thought, to effect favorably a claim my brother had against the Government” (emphasis mine): transcription, found at the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, Florida, and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, of an unpublished memoir, “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830” (hereafter “Childhood and youth”) 33-34. Twenty years later, Key West’s Stephen Mallory was pressing for a resolution of this claim in the U.S. senate: “Claim for occupation of Key West,” The Congressional globe (Washington, D.C.) 3 April 1852 952-960. For some account of the navy’s alleged depredations, see my earlier post 059–Gibraltar of the Gulf.

[16] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 30 April. John W. Simonton, a Key West proprietor who doubtless penned many of the letters of introduction Whitehead carried to Washington, was a personal friend to Barry and his family: J. W. Simonton, Key West 2 April 1832, to William T. Barry, in Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The territorial papers of the United States. Volume XXIV. The territory of Florida 1828-1834 (Washington 1959; hereafter “Territorial papers XXIV”) 685-686. Whitehead’s conference with the Postmaster General may have touched upon carriage of the mail between Florida’s southern reaches and the rest of the country, notably a citizens’ petition to Congress the previous November for “establishment of periodical and frequent mail communication” with Key West. See Key West (Fla.) gazette 23 November 1831 2:2-3; “Petition to Congress by citizens of Monroe County,” in Territorial papers XXIV 624-627; and my earlier post 043–Together apart.

[17] Leonard D. White, The Jacksonians. A study in administrative history 1829–1861 (New York 1954) 251-253; Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the course of American freedom, 1822–1832 (New York 1981) 165, 319, 336.

[18] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 28 April 1832. The president expressed to saddle maker James Lawliss his “feelings of gratitude, much enlivened by the assurance that you are a native son of Erin,” in a letter of the same date as Whitehead’s visit: “Correspondence,” The Albany (N.Y.) Argus 15 May 1832 2:3.

[19] “Childhood and youth” 33. The invitation was for dinner on 3 May: Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 2 May 1832.

[20] Whitehead, Memorandums, entry of 1 May 1832. Washington papers advertised May Balls at the Union Hotel, Masonic Hall and Carusi’s Washington Saloon. The last was arguably the most prestigious: eight days after, Carusi’s held a Queens’ Ball “in compliment to both the Queens of the first of May,” which “Members of Congress and visiters to the Metropolis are expected to attend.” On Carusi’s Saloon see James R. Heintze, “Gaetano Carusi. From Sicily to the halls of Congress,” in James R. Heintze, ed. American musical life in context and practice to 1865 (New York 1994) (75-132) 105-107.

[21] “Childhood and youth” 33. “My visit to New Jersey added new ties and strengthened old ones; my sojourn in Amboy binding me closer than ever to the place and to those residing within it.” “Childhood and youth” 34.