AMERICANS watched with apprehension, through the winter and spring of 1831-32, as an epidemic of Asiatic cholera swept westward across Europe, conscious that the proliferation of swift oceangoing vessels made it unlikely the plague’s process would stop at the far shores of the Atlantic. Fear combined with a morbid fascination to accelerate the sale of nostrums and newspapers. When word came, in early June 1832, that a ship bearing immigrants from the British Isles had introduced the deadly disease to Lower Canada, the horror was suddenly at hand.

Already in the previous summer and fall, some coastal cities had taken steps to prevent or delay its onset. New York’s mayor imposed a quarantine on all vessels from Mediterranean and Baltic ports. Seeing the want of a unified system “to prevent the introduction of this awful scourge into this happy country,” he implored port cities up and down the coast to enact similar precautions. The town council of Key West, Florida, took up his request in October 1831, and duly ordered “all vessels arriving from ports or places, where the said disease exists,” to be quarantined “northward and westward of Fleming’s Key”; no person from Key West was to “hold any intercourse” with them or their passengers.1

As collector of customs for Florida’s southern coast and one of the authors of the quarantine ordinance, William A. Whitehead was quite aware of the risk in allowing foreign vessels to come ashore. But as he journeyed northward the following spring, and drew near to the very epicenter of the outbreak, he found no firm consensus on the nature of the coming peril, the advisability of quarantine, or even the public’s need for complete and correct information.2

As it turned out, authorities in New York City were ill-equipped to handle the crisis. William Dunlap, who remained in the city, entering statistics of infections and deaths through the summer in his daily journal, epitomized the situation in a few words: “We have been preparing for the enemy, but we are not prepared.” He doubted the numbers he recorded, until the Board of Health in late August ceased reporting them. What was certain was that most who could leave did so: it’s estimated that a third of the city’s population joined the exodus. As Dunlap remarked, “the diminution of people is very great by death & flight.”3

With cholera at last a fact of American life, rare were the observers who did not blame the contagion’s spread on the moral failings of its victims. It was “generally understood,” said Dunlap, “that the sufferrers [sic] are imprudent or intemperate persons.” Eminent New York merchant John Pintard, for all his philanthropic impulses, found consolation in the fact that cholera mainly attacked “the lower classes of intemperate dissolute & filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations.”4

Physicians with direct experience of the epidemic felt compelled to assert that its victims had led dissolute lives, and to draw from the scourge a moral lesson, however much it contradicted the evidence of their own observations: “If it be not so in fact,” pleaded one New Jersey doctor, “still, for the sake of temperance and good order, let it stand recorded that the drunkard is peculiarly the victim of cholera. Let us all live and die sober men.”5

In any epidemic, the poor suffer far out of proportion to their numbers. But few among the privileged classes could grasp that greater vulnerability was a function of indigence more than intemperance. Because cholera was seen as having invaded the country from abroad, and as the immigrant poor were the most disadvantaged, and so the most afflicted, immigrants were routinely regarded as the source of the disease.

Even a man of the cloth could give voice to such sentiments, comforting his parishioners and himself that “the temperate and orderly portion of the community” was spared, while lamenting “that our country must not only be filled with refuse of other nations, but be overspread with pestilence in consequence of their landing on our shores.”6

The author of these words was the Reverend James Chapman, writing from the rectory of St. Peter’s church in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Among the “temperate and orderly portion” of his community, Chapman would have counted the family of William Whitehead. In 1832, they had been members of his congregation for nearly a decade, during which William’s father rendered long and faithful service to the vestry of the church. Reunited with his parents in May following an absence of a year and a half, Whitehead would have gone to St. Peter’s with them the next morning, where all could give thanks for his safe return.

James Chapman’s remarks occur in one of the hundreds of letters he exchanged over a span of two decades with his friend Thomas Naylor Stanford, a partner in the New York firm Stanford & Swords, the main publisher of texts and tracts for the Protestant Episcopal church. As cholera descended on the metropolis, Chapman’s family took in the two younger Stanford children, pleased, he wrote, to “contribute any thing to the relief of your mind in this time of distress.”7 The rector of St. Peter’s gave his New York friend repeated assurances of the children’s well-being, and of the healthful environment they enjoyed at Perth Amboy.

A twenty-mile steamboat ride, numerous kinship ties and other affinities linked the two communities, and many citizens of Perth Amboy felt alarm and worry at the plight of their big-city neighbors. So far, however, the smaller city had been fortunate, and some were convinced that Amboy, designated at its origins a “sweet, wholesome, and delightful place,” would remain forever free of the disease. Others, Chapman included, were not so sanguine.8

During a single week in June, three ships from Liverpool stopped at Amboy, together carrying more than 500 passengers.9 Not all disembarked there, and of those who did most soon boarded a smaller vessel for other ports. The recent appearance in Jersey City of an “unusual number of foreigners” led a newspaper editor to conclude that these were emigrants recently deposited at the Perth Amboy wharves, with the intent of circumventing the strict quarantine requirements of New York.10

After a brief interval (“We have had no arrival of emigrants here this week,” wrote Chapman11), Amboy saw “some excitement” when the ship Albion from Bristol landed passengers, “having been in our waters but 24 hours.” The new arrivals numbered 190, all seeming “very healthy,” but the speed with which they were entered and the ship sent on its way confirmed the suspicions of New York authorities that these landings were a means of evading quarantine.12

Those recalling the fraudulent practices of Perth Amboy’s previous customs collector would have been little surprised by such an imputation.13 What seemed to bother its citizens more was any suggestion that theirs was an unhealthy city. An anonymous letter to the Daily Advertiser in Newark, a town hard-hit by cholera, exulted in Amboy’s “unusual share of good health” amidst the ravages of the pestilence: “The elevated situation of our city, its spacious streets and dry soil, together with a refreshing and invigorating sea breeze, concur to render it a delightful retreat during the warm season.”14

As if in retaliation for the boast, another letter of the same date, also purportedly from Perth Amboy, found its way to newspapers in New York. It gave a decidedly contrary view:

Four or five cases of cholera, or something strongly resembling it have occurred here. A French brig arrived here to-day and there are two ships, coming up the bay–one with 190 foreigners on board.15

This report astonished James Chapman, who called it “shameful”. “If I had had the least idea,” he told Stanford, “that any report of Cholera here had been sent to N. Y. I should have written without fail.” As was “the case in all general calamities,” he admitted, “some of the best members of society must be expected to be taken away” along with “the wicked and the worthless,” but the insinuation that cholera had struck Perth Amboy was a complete falsehood. How could it have done so, when no vessels had arrived from abroad for the past three weeks?16

A local physician confirmed that “not a case of Cholera or other malignant disease had occurred at Perth Amboy this season.” New York papers rushed to print his rebuttal,17 but efforts to trace the false report to its source ended in failure. “Many of our citizens,” Chapman grumbled, “have been much displeased at the publication of a statement so totally unfounded in fact, but the author of the fabrication has not been discovered.”18

Evidence of how Whitehead spent the summer of ’32 is scanty and indirect. At least once, he lent a hand at the custom house, calculating duties on cargo taken off one of the three ships from Liverpool.19 But within the limits imposed by the epidemic and his official duties to keep in contact with superiors in Washington, and more sporadically with his deputy at Key West, Whitehead seems to have made a beginning of studies that would coalesce into the major works of the following decades. Finding refuge, for the better part of four months, in East New Jersey’s ancient capital, he could not but heed the call of its history.

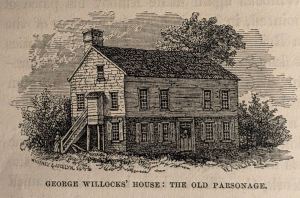

Just what research he may have pursued in the “garrets and lumber-rooms” of Amboy’s old homesteads, or among the records of the Eastern Board of Proprietors, may never be known. But one project appears to have taken shape during this summer sojourn. Whitehead sat and sketched at least four of the town’s historic sites, views featured a quarter-century later in his monograph on Perth Amboy: scenes that have long since vanished.20

Had their “intended London of America” not fallen “so far short” of its founders’ expectations, these melancholy glimpses might never have existed, material progress operating in all epochs as the enemy of place. The isolation and stillness imposed by the 1832 epidemic may also have had a part. In 1849, during another, even more lethal summer of cholera, Whitehead gratefully found himself once again in this “sweet, wholesome and delightful” spot, weaving impressions and insights into the words that would make up four extended “letters from Amboy.” For, “as all acknowledge who know it now,” he would write, “there are inducements sufficiently operative at all times, independent of local ties and attachments, to draw one hither.”21

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.09.25

[1] “Proclamation by Walter Bowne, Mayor of the City of New-York,” New-York (N.Y.) evening post 6 August 1831 2:3, New-York (N.Y.) commercial advertiser 8 August 1831 2:5; “Proclamation, by Walter Bowne, Mayor of the City of New York,” and “Circular,” New-York commercial advertiser 12 September 1831 2:6; Key West (Fla.) gazette 19 October 1831 2:3, 3:1. The ordinance “For preventing the introduction of Cholera into the City of Key West” was reprinted in each issue of the Gazette until what was apparently its last, dated 5/8 September 1832.

[2] “The Devil is in the Doctors again,” reflected New York’s former mayor Philip Hone. “Whenever cases occur in which the public safety requires Union, Confidence and good Temper, the members of that fractious Profession are sure to fall out among themselves and the public Health is sacrificed to the support of theoretical opinions.” Philip Hone diaries, 1826-1851, New-York Historical Society MS 1549, 5:232, entry of 3 July 1832; printed in Allan Nevins, ed. The diary of Philip Hone 1828-1851 (2 vols. New York 1927) 1:60. For disagreements over quarantine in this period, see Charles E. Rosenberg, The cholera years. The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago and London 1962; hereafter “Rosenberg, The cholera years”) 79-81.

[3] Diary of William Dunlap (1766-1839). The memoirs of a dramatist, theatrical manager, painter, critic, novelist, and historian (3 vols. Collections of the New York Historical Society, 62-64. New York 1930; hereafter “Diary of William Dunlap”) 3:603-605, 611, entries of 2, 9, 12, 21, 30 July. Dunlap was skeptical, at first, of the nature and gravity of the disease in New York, but came to believe many cases went unreported. In these latter suspicions he was not alone: cf. Rosenberg, The cholera years 19-20; Geoffrey Marks and William K. Beatty, Epidemics (New York 1976) 201; Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham. A history of New York City to 1898 (Oxford University Press 1999) 589-591. For doubts cast on official reports in Newark, see Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 10 August 1832 2:2; 13 August 1832 2:3; 15 August 1832 2:4; 16 August 1832 2:3. For Newark’s experience of the 1832 epidemic, see “Reminiscences of the Cholera of ’32,” Newark daily advertiser 19 June 1849 2:3; Stuart Galishoff, “Cholera in Newark, New Jersey,” Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences 25:4 (October 1970) (438-448) 438-445.

[4] Diary of William Dunlap 3:603, entry of 7 July; Letters from John Pintard to his daughter Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson 1816-1833 (4 vols. Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 70-73. New York 1940-1941), 4:72, entry of 13 July, and cf. 4:75, entry of 19 July.

[5] The conclusions of (probably) Timothy Kitchell (“Dr. Kitchel”) of Whippany, “a gentleman of close observation and great candour,” were quoted approvingly by Samuel Hayes Pennington, Secretary of the Medical Society of New Jersey, in “Report for the Eastern District,” Transactions of the Medical Society of New Jersey (1833) (301-308) 308. Pennington was a former schoolmate of Whitehead’s in Newark, and would later collaborate with him in various educational endeavors. It soon became clear that New Jersey physicians, too, might succumb to “the prevailing epidemic”; John Chetwood of Elizabethtown died in the midst of tending to its victims. James Chapman, Perth Amboy 15 August 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers, MC 608, Special Collections and University Archives, Alexander Library, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. (hereafter “Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers”); J. Henry Clark, The medical men of New Jersey, in Essex District, from 1666 to 1866 (Newark 1867) 34; [William O. Wheeler and Edmund D. Halsey,] Inscriptions on tombstones and monuments in the burying grounds of the First Presbyterian Church and St. Johns Church at Elizabeth, New Jersey, 1664-1892 ([Morristown, N.J.? 1892?) 293 (no. 13).

[6] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 22 June and 7 July 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[7] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 6 July 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[8] Whitehead quoted the East Jersey Proprietors’ proposals for Perth Amboy’s settlement in, among other places, an untitled letter signed G. P., dated “Perth Amboy, June 5th, 1849,” Newark daily advertiser 7 June 1849 2:1. “I find that some of the Amboy people are of opinion that this place will not be visited by the Cholera. I have my doubts–but hope for the best.” James Chapman, Perth Amboy 23 July 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[9] All three ships were bound for ports in Virginia. The first two, James Cropper arriving on 5 June and Tally-ho on 7 June, carried 180 steerage passengers each. The ship Richmond landed on 11 June, with 174 passengers. New-York evening post 6 June 1832 3:1, 13 June 1832 2:6; National gazette and literary register (Philadelphia, Pa.) 8 June 1832 2:6; New-York commercial advertiser 11 June 1832 1:6, 13 June 1832 3:1; New-York (N.Y.) American 13 June 1832 2:6; Baltimore (Md.) patriot & mercantile advertiser 21 June 1832 3:1.

[10] “How to avoid quarantine-law!” The Bergen County courier (Jersey City and Hackensack, N.J.) 20 June 1832 2:1.

[11] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 22 June 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[12] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 25 June 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers. A record of Albion’s journey kept by Stephen Davis, a missionary for the Baptist Irish Society, was published as Notes of a tour in America, in 1832 and 1833 (Edinburgh 1833) 31-45. More than 600 tons of wrought iron plates and fastenings, needed for construction of the politically well-connected Camden and Amboy Rail Road, were aboard Albion, and may have influenced the swift transfer of its passengers to a New York-bound steamer: see Cargo Manifests “Inward”, June 1825–ca. September 1877, Perth Amboy Collection District, Records of Customhouses and Collection Districts, Record Group 36, Records of the U. S. Custom Service, National Archives and Records Administration, hereafter “Perth Amboy Cargo Manifests.” The fixtures that Albion delivered for the Camden and Amboy are described in J. Elfreth Watkins, The Camden and Amboy Railroad. Origin and early history (Washington [1891]) 32.

[13] For some history of the notorious “case at Amboy,” see my earlier posts 010-The entrepôt and 090-Ascension.

[14] Newark daily advertiser 19 July 1832 2:2. This paean to the healthfulness of Perth Amboy borrowed some of the wording used during an 1811 yellow fever outbreak: see David Hosack, Observations on the laws governing the communication of contagious diseases, and the means of arresting their progress. [Read before the Literary and Philosophical Society of New-York, on the 9th of June, 1814.] (New-York 1815) 37 and note.

[15] “Amboy,” New-York commercial advertiser 20 July 1832 2:4; New-York American 20 July 1832 2:5.

[16] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 21 July 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[17] “No cases of Cholera have occurred, or cases resembling it. No French brig arrived that day, nor at any time this year. Nor have any ships with passengers since the ship Albion from Bristol, on the 22d June last, all of whose passengers were in perfect health.” New-York evening post 21 July 1832 2:5; New-York American 21 July 1832 3:1-2; New-York commercial advertiser 23 July 1832 2:3. The “Dr. Smith” who issued this correction was likely Charles McKnight Smith, an 1827 graduate of the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons; cf. James Chapman, Perth Amboy 23 July 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[18] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 23 July 1832, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[19] An entry of £16 worth of tableware, imported on 8 June by the ship Tally-ho, was made out in Whitehead’s hand. The record shows that a duty of $13 was levied. Perth Amboy Cargo Manifests.

[20] The engravings of these scenes bear Whitehead’s initials and the year 1832 in which they were drawn. They depict the house of East Jersey Proprietor George Willocks, which became the parsonage of St. Peter’s (of which Willocks and his wife were benefactors), taken down, Whitehead says, in 1844; St. Peter’s Church, replaced by the current structure in the 1850s; the Parker family mansion known as The Castle, demolished in 1942; and the Courthouse, portions of which survive in the modern City Hall. The four images are found in William A. Whitehead, Contributions to the early history of Perth Amboy and adjoining country, with sketches of men and events in New Jersey during the provincial era (New York 1856) 82, 137, 227, 252. Whitehead’s sketch of the Long Ferry Tavern, ibid. 262, bears no date but possibly belongs to this series. This and three earlier posts (001–Arrival, 003–The Castle, and 036–Pleasures, plants and palaces) each reproduce one of these views.

[21] Newark daily advertiser 7 June 1849 2:1. Whitehead’s many contributions to the Newark Daily that summer include three other Amboy letters signed G. P.: “Amboy, and its history,” published 12 June; “Amboy–its reminiscences,” published 19 June; and “Flying machine–steam–the past,” dated 4 July and printed 6 July.