POETS of old, and not only poets, looked back with longing to a supposed Golden Age, a remote past in which peace and prosperity reigned supreme. Yet, in the life and times of William A. Whitehead, it was hard for some to imagine things could have ever been better.

In one corner of New Jersey’s map, however, Whitehead found a place where it almost seemed a Golden Age once had been. On the “good lively land” appointed for “a convenient town” and future provincial capital, and on the excellent harbor, the PORTVS OPTIMUS of its city seal, were pinned hopes of a maritime metropolis, an American London. But “we yet look back upon years already fled,” Whitehead marveled, “for the most renowned, perhaps the most prosperous period of its history, although the population at the present day may be greater.”1

Perth Amboy’s citizenry had surely increased in number since colonial times, but included very few descendants of the families that had once featured so prominently. Indeed, “of the original population, not even one family name remains as a memento of the race.” Whether the disappointment of its originators’ lofty hopes was a cause or a consequence, Whitehead judged economic factors to be “particularly operative”: there simply wasn’t “sufficient business to excite the enterprise and occupy the time of the youth of the city”; and as its young people formed “connections elsewhere, the family names have become extinct on the death of the parent stocks, and ‘the place that knew them, knows them no more.’”2

This scattering of new generations, concurrent with the passing of the old, was in no way unique to Perth Amboy. The expansion of settlement and the almost universal American “inclination for change” had pretty much demanded it. Nonetheless, Whitehead felt it created “a disadvantage under which family associations labor in this land of ours,” with a melancholy result:

Seldom does the man close his pilgrimage beneath the roof which sheltered him when a boy, and very rare are the instances where the grand child sports upon the grounds which his father’s father secured for his inheritance–occupies the dwelling which a still more distant and honored ancestor may have erected–walks the same streets–fills the same responsible stations in the same community, and at last finds his grave among the crumbling memorials of many progenitors in the same consecrated ground.3

Yet there loomed, in the shape of the mansion dubbed Parker Castle, one noteworthy exception to the dispersal of Perth Amboy’s foremost families. “Six or seven generations” of the same line had, by Whitehead’s time, filled the halls of this ancestral seat, savored its cheerfulness and charity, “been trained to usefulness,” and emerged “from its portals to mix in the active business of life….” Nearly as many generations had found, in the same local churchyard, their final resting place.

Parker Castle’s original stone portion was believed the project of John Parker, the son of an early settler of Woodbridge, New Jersey. John succeeded his father as a member of the governor’s council, being found “of very good æstates, and capacity, … and zealously well affected to His Majesty and his service.”4 The Castle became the birthplace of John’s son James who, as family patriarch, would greatly enlarge it with a frame annex built on the adjacent bluff. It was presumably in this newer, more comfortable wing that James Parker at age 72 also closed his earthly sojourn, but only after events had brought about a long, at times harrowing interruption in his peaceful rule of the manor.

This progenitor of the many living Parkers of Whitehead’s acquaintance was “a man of tall stature, and large frame, possessing a mind of more than ordinary strength and vigor….”5 It’s a description Whitehead would have drawn mainly from the recollections of James Parker’s descendants. But of the man’s talents and energy the historical record gave ample witness.

Parker had succeeded his father as one of the East Jersey proprietors, becoming a member of the Board of Proprietors and, in 1762, its president. Two years later, he entered the council of William Franklin, New Jersey’s last colonial governor,6 where, attuned to the perilous politics of the day, he advised on the deepening discontent with British taxation,7 and as war became imminent likely authored a 1775 address seeking to balance “our Zeal for the Authority of Government on the one Hand, and for the Constitutional Rights of the People on the other….”8

With the war came a swift scattering of the Amboy élite, for while there was little open conflict before the final break “the strong tory bias of almost every rich, influential, or respectable family” cast over the city a pall of suspicion.9 General Washington knew well the locals’ “disaffection” with the patriot cause, and worried that “unless It is checked and overawed it may become more general and be very alarming.” In July 1776, with some 4,000 enemy troops already landed on Staten Island–“which is quite contiguous”–Washington saw Perth Amboy as a likely first foothold for the king’s forces on Jersey soil.10

Whether from fear, allegiance or hope of advantage, many leading families left the city for British-held New York or further afield. Whitehead, although “not disposed to yield precedence to any one in patriotism,” couldn’t repress sentiments of “sympathy and compassion for the sufferings and trials” of those Loyalist families, “whose only crime it was” to choose “laws and allegiance with which they were conversant, in preference to embarking upon the wide and uncertain sea of disorder and revolution….”11

The royal governor stood by his king, and paid a price for that loyalty: arrested after a brief tenancy of the mansion built for him at Perth Amboy, the American-born Franklin endured long confinement and permanent exile from the land of his birth. In the months leading up to the governor’s arrest, James Parker stopped attending council meetings, packed up his essential papers and effects, and moved his family to a rural estate 40 miles west. Parker returned to Perth Amboy in early 1776 for meetings of the Board of Proprietors. But when he and a fellow Hunterdon County landholder, Walter Rutherfurd, declined to abjure the Crown and swear fealty to the newly independent New Jersey, they were jailed on suspicion of being “persons disaffected to this State….”12

Later released to their families and a more relaxed form of detention, the two were part of a proposed prisoner exchange that Parker, reflective of his social standing, received a fortnight’s parole to travel to New York and negotiate. But the pair’s movements remained restricted for the duration of the war.13

William Dunlap, who as a lad experienced the British occupation of Perth Amboy, would furnish Whitehead with compelling images of its disruptions and miseries: “my father’s house filled with officers, his kitchen and out-houses with their servants and soldiers”; British expeditions into the rebellious countryside, with “a long train of wagons to procure forage” that returned laden instead with wounded soldiers; the “brutal licentiousness, which even my tender years could not avoid seeing….”14 James Parker would be forgiven for not wishing to expose his children to these terrors.

Returning to Amboy with the coming of peace, Parker resumed his active service on the Board of Proprietors, and soon recovered his rights as a full citizen of the republic. Now in his sixties, in spite of his past refusal to embrace the American cause, he “was long solicited and as long refused” to run for Congress under the new Constitution, finally declaring candidacy, but “so late that it answered no other purpose than to show what I might have done, had I declared in time.”15

The son who inherited James Parker’s full name was born in the first year of the war and of his parents’ exile. Although he spent his early life at a distance from Amboy, his father’s legacy of prominence in the affairs of the city–and the state–became, perhaps inevitably, his own.16 The younger James left the Castle in the charge of three unmarried sisters and moved to a dwelling just steps away, where a granddaughter recalled him being “continually on his feet,” even having a desk made “so that he might stand at it.”17 He entered the New Jersey assembly in 1806 at age 30, representing Middlesex County for all but one of the next dozen years. He returned to the legislature in 1827, to advocate for a canal traversing the state.

With government support, Parker argued, this canal would be a boon to the assembly members’ constituents, affording “an opportunity to improve their condition at home, without emigrating to more favoured States, as has been too much the case in New-Jersey….”18 He may have hoped privately that one or more of his sons would thus be encouraged to remain in Perth Amboy and fill “the same responsible stations in the same community”; if so, he hoped in vain. The canal’s construction would rely on private capital, not public monies as Parker had favored, but its coalescence with the Camden and Amboy Railroad into the formidable Joint Companies, over which Parker would long preside, kept him at the center of the state’s political life.19

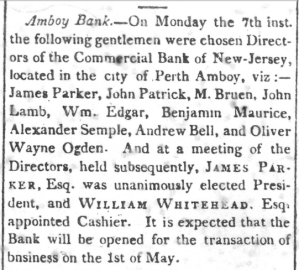

A more modest, less potent enterprise took shape in the Commercial Bank of New Jersey, which began operations in May 1823 with Parker as president. Upon the appointment of Whitehead’s father as its first cashier the Whitehead family moved from Newark to Perth Amboy, and thirteen-year-old William became “general clerk” of the bank, at an annual salary of $100.20 James Parker would soon recognize his young clerk’s abilities and, when the time came, suitability as a husband to his daughter. And so, as a slender shoot grafted to a sturdy stock, Whitehead came to find his life ever linked with the house of Parker.

Merchant, banker, state legislator, collector of customs (the last two years of his tenure overlapping Whitehead’s own at Key West), member of Congress, large landholder, patron of learning, entrepreneur, churchman, father-in-law: the roles and interests of the second James Parker that paralleled, influenced or even defined the younger man’s are too numerous to receive but a mention here. They will, with luck, be expanded upon over time.

One tie, however, warrants more than a mention, as it reaches beyond these two men to encompass generations and even centuries. Ownership, management, surveying and disposition of New Jersey lands had engaged both the elder James Parker and his son, as landholders in their own right and as agents for the East Jersey Proprietors. These responsibilities made them adept producers, receivers and custodians of a vast documentary inheritance, one that supported, among other endeavors, a spirited defense of New Jersey’s prerogatives as colony and state.21

Not by accident did each James Parker serve in his day as a commissioner for fixing the borders with New York, a problem that, although technically settled in 1769 in the case of the northern boundary, and in 1833 in the case of the eastern, would be agitated for years thereafter. William A. Whitehead, in his turn, ventured fearlessly into the papers illuminating these arduous conflicts, as well as myriad other controversies in New Jersey’s past.22 In doing so, he made ample space for his own distinctive achievements, as the foremost exponent of his state’s history, and a worthy heir to the Parker legacy.

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.09.27

[1] The description of Amboy Point as “good lively land” is found in the letter of deputy governor Thomas Rudyard, dated East-Jersey 30 May 1683, to B. G., printed in George Scot, The model of the government of the Province of East-New-Jersey in America (Edinburgh 1685) 152, repr. in William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary governments: a narrative of events connected with the settlement and progress of the province, until the surrender of the government to the Crown in 1702 [1703] (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1. Hereafter “Whitehead, East Jersey”) ([New York] 18461) 280, (Newark 18752) 413. Instructions for founding a “convenient town” figure in the “Proposals by the proprietors of East-Jersey, in America, for the building of a town on Ambo Point…,” known to Whitehead only through their publication in Samuel Smith, The history of the colony of Nova-Cæsaria, or New-Jersey … (Burlington, N.J. 1765) 543-546, and reprinted in Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 211-214, (18752) 319-322; William A. Whitehead, Contributions to the early history of Perth Amboy and adjoining country, with sketches of men and events in New Jersey during the provincial era (New York 1856. Hereafter “Whitehead, Contributions”) 4-5. Whitehead may have grown receptive to the idea that Perth Amboy could still enjoy a more prosperous future, but not without sacrificing much of its antique appeal. “This town,” he wrote in the 1840s, “was a favorite project of the proprietaries, and they prefigured for the object of their solicitude a destiny which has never been realized.” Thirty years later he altered the concluding words to read, “a destiny which, as yet, has not been realized [emphasis mine].” Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 108, (18752) 142. Cf. my earlier post 036–Pleasures, plants and palaces.

[2] Whitehead, Contributions 59-60; Reference to the assessors’ books in 1832 showed that all but eleven of the 150 residents found there 30 years earlier had vanished, most having presumably “before this given place to others.” Ibid. 60 note 1. The minister of the Whitehead family church also noted these disappearances: “On his taking charge of the parish [in 1809], he ascertained the number of families belonging to the Church to be about twenty, and the number of communicants to be twenty-five. Of this latter number only eleven survive [in 1830]; nine continuing here, and two having gone away to reside in a distant island.” James Chapman, Historical notices of Saint Peter’s Church, in the City of Perth-Amboy, New-Jersey, … (Elizabeth-town 1830) 21.

[3] G. P., “Amboy, and its history,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 12 June 1849 2:1-2. Whitehead, Contributions 137-138, restated these sentiments largely verbatim, except to add “the abolition of all laws of entail” as a reason that many descendants sought their fortunes elsewhere.

[4] Robert Hunter, New York 3 May 1718, to the Lords of Trade, in William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 4. Administrations of Governor Robert Hunter and President Lewis Morris. 1709-1720 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 4. Newark 1882) 363-364; cf. ibid. 331, 336, 377 n.1. For biography of John Parker, see ibid. 333 n.1; Whitehead, Contributions 129-130. Parker Castle was the subject of my earlier post 003–The Castle.

[5] Whitehead, Contributions 135. For biography of the first James Parker (1725-1797), see Frederick W. Ricord and William Nelson, edd. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 9. Administrations of President John Reading, Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Pownall, Governor Francis Bernard, Governor Thomas Boone, Governor Josiah Hardy, and part of the administration of Governor William Franklin. 1757-1767. (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 9. Newark 1885. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 9”) 446 n.1; William S. Stryker, ed. Documents relating to the Revolutionary history of the State of New Jersey, 1. Extracts from American newspapers. Vol. 1. 1776–1777 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 2, 1. Trenton 1901) 454; William Nelson, New Jersey biographical and genealogical notes from the volumes of the New Jersey Archives with additions and supplements (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 9. Newark 1916) 173-174.

[6] Franklin reiterated a recommendation first made by his predecessor, Josiah Hardy, in 1762, but confirmation from London of his appointment to the governor’s council did not reach Parker for another two years. See NJA ser. 1, 9:366, 427, 483.

[7] James Parker, Perth Amboy 22 January 1776, to Governor Franklin, in Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society [ser. 1] 9:2 (1862) 96.

[8] Frederick W. Ricord, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 18. Journal of the Governor and Council, 6. 1769–1775 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 18. Trenton 1893) 488.

[9] Whitehead, Contributions 142. William Franklin’s former personal secretary Charles Pettit, who threw in his lot with the Revolution, named Perth Amboy “almost the only spot of Ground in America where a Friend to American Liberty is a disgraceful Character.” Charles Pettit, Amboy 10 August 1775, to Joseph Reed. Joseph Reed and Esther De Berdt Papers, 1757-1874, New-York Historical Society. According to Whitehead, Pettit settled for a time in the former dwelling of John Johnstone, one of Perth Amboy’s first settlers, before removing to Philadelphia around the time of Franklin’s arrest; see Whitehead, Contributions 71 n.25.

[10] George Washington, New York 4-5 July 1776, to John Hancock, in W. W. Abbot, ed. The papers of George Washington. Revolutionary War Series, 5. 16 June 1776–12 August 1776 (Charlottesville, Va. 1993) (199-203) 200. Cf. Whitehead, Contributions 329.

[11] G. P., “Flying Machine–steam–the past,” Newark daily advertiser 6 July 1849 2:1.

[12] Entries of 15 and 20 August 1777, Minutes of the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey (Jersey City 1872) 117, 121.

[13] For a full account of James Parker’s rural retreat and wartime ordeal, see Charles W. Parker, “Shipley: the country seat of a Jersey Loyalist,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society n.s. 16:2 (April 1931) 117-138.

[14] William Dunlap, A history of the American theatre (New-York 1832) 236-237, quoted in Whitehead, Contributions 343 and cf. ibid. 339; William Dunlap, History of the rise and progress of the arts of design in the United States (2 vols. New-York 1834) 1:248-249, ed. Alexander Wyckoff (3 vols. New York 1965) 1:293-294.

[15] Whitehead, Contributions 134-135.

[16] For biography of the second James Parker (1776-1868), see Richard S. Field, Address on the life and character of the Hon. James Parker, late President of the New Jersey Historical Society. Read before the Society, January 21, 1869 (Newark 1869; hereafter “Field, Address”), also printed in Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society ser. 2, 1:3 (1869) 109-135.

[17] Katherine M. Beekman, “A colonial capital. Perth Amboy, and its church warden, James Parker,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society n.s. 3:1 (1918) (1-25) 11.

[18] James Parker, Report of the Committee on the Delaware & Raritan Canal (n.p. 1827); repr. in Field, Address, Note B.

[19] For some account of the Joint Companies, see my earlier post 081–The monopolists.

[20] Unpublished memoir, in a typewritten transcription entitled “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” copies of which are found at the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, Fla., and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Page 16 of the transcription relates the beginnings of the Commercial Bank. See also my post 004–Birth of a bank.

[21] John Stevens, Walter Rutherfurd and James Parker presented New Jersey’s claims at the 1769 conference that settled its northern boundary with New York. Before the New Jersey Historical Society Whitehead exhibited “letters, briefs and memoranda” in his possession, evincing Parker’s leading role in the negotiations, his “thorough acquaintance with the subject, and the most untiring devotion to the interests of the province.” “The northern boundary of New Jersey,” Newark daily advertiser 19 May 1859 2:1-2; Wm. A. Whitehead, “Northern boundary line. The circumstances leading to the establishment, in 1769, of the northern boundary line between New Jersey and New York. A paper read before the New Jersey Historical Society, May 19, 1859,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society [ser. 1] 8 (1859) (157-186) 176. Whitehead again presented “original manuscripts, from his own library” at a meeting of the Society, during which he read a paper by the second James Parker on New York’s attempts to claim sovereignty over the waters along New Jersey’s eastern shoreline; Parker had served on three successive New Jersey commissions to settle the controversy. See James Parker, “A brief history of the boundary disputes between New York and New Jersey. Read before the New Jersey Historical Society, January 21, 1858,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society [ser. 1] 8:3 (1858) 106-109, and cf. ibid. 92; Field, Address 12-16, repr. Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society ser. 2, 1:3 (1869) 120-124; [W. A. Whitehead,] “Boundary question between New York & New Jersey. Substance of conversation with Mr. Parker June 17, 1856,” James and William Alexander Papers, Box 13/7, Manuscript Group 70, New Jersey Historical Society.

[22] Whitehead in the years 1865-1870 did battle with New York historians in sometimes acrimonious debates, particularly over the status of Staten Island. See the partial compilation in William A. Whitehead, “Eastern boundary of New Jersey. A review of a paper on the waters of New Jersey, read before the Historical Society of New York, by the Hon. John Cochrane, (Attorney-General of that State,) and a rejoinder to the reply of ‘A member of the New York Historical Society’,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society [ser. 1] 10 (1865-66) 89-158.