AMONG the vestiges of an all-but-forgotten colonial capital and seaport, William A. Whitehead grew to his maturity. He came of age as well within two old and intersecting family orbits.

A crucial link had been forged before his birth, by the 1792 marriage of Janet “Jennet” Parker of Perth Amboy to Edward Brinley, scion of a venerable Newport, Rhode Island, dynasty. Brinley, who was barely 20 years of age when the Revolution swept over New England, had entered the King’s army and served with Cornwallis during the siege of Yorktown. At war’s end he moved to Nova Scotia, but later returned to Rhode Island and his native city, another maritime center whose most flourishing days lay in the past. There, he reclaimed his family’s ropemaking business, but without much success.1

With Janet, Edward Brinley had four children who lived to adulthood: three daughters–Gertrude Aliph, known by her second name; Elizabeth Parker; and Catharine Sophia–as well as a son, Francis William. Their mother’s early death and their father’s remarriage led to a geographical separation: the children remained in New Jersey as Edward started a second family in Newport.

Perth Amboy’s Commercial Bank, formed in 1823, was another link between the Parker and Brinley clans. Under the late Janet Brinley’s brother James Parker, who was its president, her son Frank Brinley became the bank’s bookkeeper. In Frank’s frequent absences many responsibilities devolved upon William A. Whitehead’s father, who had moved from Newark to assume the post of cashier, and also on young William as “general clerk.”2

Having no formal schooling since leaving Newark at age 13, William nonetheless found that the quiet of Perth Amboy and the light activity of its Bank allowed ample space for self-improvement. He would later record that he “at different times took lessons in French, and might have been called a diligent reader.”3

When he was 16, “a close friendship” developed with the youngest of Frank Brinley’s three sisters, who was then about 24. Catharine Brinley urged William to take up drawing, a talent he had first discovered as a boy. With her encouragement, he began to copy engravings in pen and ink, and became “quite an artist for young ladies’ albums.” Cate Brinley’s “many incentives” (what was their nature he doesn’t specify) “to reading, to composition, and other literary pursuits” likewise were “not unheeded….”

Until this time, Aliph, Elizabeth and Catharine had probably all lived in the ancient mansion called Parker Castle, together with their three maternal aunts, James Parker’s unmarried sisters. But Aliph and Elizabeth soon were wed, within a year of one another, to two ministers.4 Cate, like the three maiden aunts, never ventured into matrimony, although she seems, in an 1830 letter from Newport to one of those aunts, to recall some dalliance whose memory was still fresh:

It approaches near the time of the year when the play of “feelings & sentiments” began. I trust there will be no periodical return of the effects–& that it may be classed with whooping cough & smallpox, to be suffered but once in the course of man’s life–for really there was too much of “Love’s labour lost” for me, & catch me if you can in such play again.5

Stubbornly independent, Catharine made the most of life in the domain of “the Misses Parker.” The Castle’s renowned gardens boasted an arbor and a beloved shade tree (“Cate’s Willow”) that, either by origin or mere association, were regarded as personally her own.6

The other Brinley sisters struggled to sustain their ties of affinity and affection over long distances, corresponding at intervals with their Newport relations, with one another, and with Catharine and their Parker cousins. But Cate, who still resided in Perth Amboy, remained the physical embodiment of the Parker-Brinley alliance formed by their parents’ marriage.

A cousin and bosom companion of James Parker’s daughter Margaret, Cate joined her in running a regular benefit for their common church of St. Peter’s, and even wrote from afar concerned for its management. She rendered similar service to her father’s congregation in Newport, raising funds for “the discouraged Missionary Society of Trinity Church, whose thinned ranks have moved my compassion to join & support as I may.”7 St. Peter’s greatly depended on the exertions of Cate and Margaret: regretting one of their occasional visits to Philadelphia, its rector once commented, “Our band of young ladies is now much reduced in numbers.”8

Catharine Brinley once confessed to possessing a “restless spirit,”9 and for a woman of her background was fairly adventurous. She traveled, sometimes alone, to visit family and friends, and proved a keen observer of human nature in all its variety. But she herself became a focus of unwanted interest, when Andrew Jackson and his retinue stopped at Newport in June 1833.

During an evening reception, wearing an old shawl and “miserable” bonnet, she unexpectedly came face to face with the President. Introduced as “Miss Brinley of Perth Amboy,” she took Old Hickory’s hand, and bowed “as low as her trembling knees could go without touching the floor, under the flashing eyes & keen observation of Ministers, Generals, Deputies, Committees & all the mobility of the Land.” Then, “before I had quite recovered myself,” Vice-President Van Buren made her the object of his unbroken attention. “I was not a little annoyed, as I wanted to observe the scene,” she wrote. “I more than once wished him in the Red Sea, tho’ it has since afforded me some amusement.”10

In 1834, Frank Brinley moved his father and stepmother from Newport to Perth Amboy, where they would live out their remaining days. For Catharine, this sudden proximity may have been a cause of some anguish.11 Her stepmother died within two years, but her father Edward, then approaching eighty, would live to 95. Cate, her parents’ youngest daughter, survived her aged father by only four and a half years.

After leaving Amboy at the beginning of the 1830s to become collector at Key West, Whitehead kept up a steady correspondence with Catharine, but none of these letters has been found. He must have retained copies of his missives, as a memoir later compiled for his grandchildren includes an excerpt from one such letter, humorously seeking Cate’s approval of his then unmarried state:

Were you ever in a bachelor’s establishment? If not you have no idea of all the comforts incidental to a life of single blessedness. There is no difference of opinion, the will of one is the law and every thing goes on smoothly. There is something, I acknowledge, about the one plate, the one tea cup, the one knife and the one fork, not altogether comme il faut, but that is a discrepancy your friends are always willing to do away with for you….12

If Catharine reacted to this portrayal, her answer has not been preserved. Emblematic of her devotion to both William and Margaret, after their 1834 marriage in Perth Amboy she accompanied them on their wedding tour through New England and the Hudson Valley.13

Perhaps as the consequence of an illness, Catharine experienced a substantial hearing loss. In 1835, she sought out Philadelphia’s celebrated surgeon Dr. Joseph Togno. His “infirmary” on Locust Street near 9th Street, with its motto “Let the deaf hear,” claimed to have cured dozens of patients.14 Cate wrote of her frustration, however, at the frequent delays in treatment and, along with some members of the medical community, doubted its vaunted efficacy. We don’t know how long she continued as Togno’s patient, or whether her hearing was ever restored.15

The elusive intimacy between Cate Brinley and William Whitehead left its most telling traces in a trio of friendship albums, dating from the first year of their acquaintance to the eve of William’s removal to Key West.16 These volumes passed between the two friends and among others in their circle, evolving, in Catharine’s words, into a “Repository of Remembrances” for their owner as he prepared to embark for the distant South. Their contents, primarily verses copied from newspapers, journals, scrapbooks or other albums, range from the didactic to the sentimental, and reveal that Cate and the others shared young Whitehead’s pleasure in language, meter and rhyme (though not, at least as far as Cate is concerned, his zeal for penmanship).

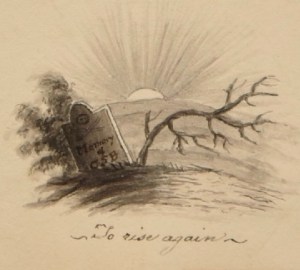

While many pieces in these albums were Cate’s selections, they were seldom her words. Only in two or three places, “since I cannot write any” did she “throw aside all Poetry” and speak to William plainly: “I shall often miss you, and very often think of you,” she wrote. Her inmost feelings are to be sought, perhaps, as much in the artwork as in the text with which she embellished these keepsakes: drawings of an antique poet with a lyre; a bird flying out of its opened cage; a forgotten tombstone bearing her initials, with behind it a rising sun.

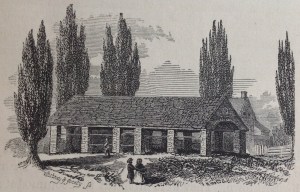

With William’s permanent return to the North in 1838 came a prospect of more direct, more frequent contact with the friend of his youth. But Whitehead was by now a family man, and more constantly employed. Two of Catharine’s sketches of colonial Amboy, depicting the central market building and the governor’s mansion, were engraved for the monograph Whitehead devoted to the city and its history, issued soon after her death.17 But how much he and Catharine Brinley saw of one another in her later years is unknown. Such encounters would have been brief ones, and tinged with sorrow at the swift passage of time.

It’s much to be regretted that not one of the many letters between the pair has come to light: these would bring us still closer to Cate, whose individuality deserves to be better known, and would disclose a great deal about the friend whose longtime confidante she became, having been, as Whitehead admitted, “made for many years the depository of every important circumstance affecting me.”18

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.09.11

[1] The year before Edward Brinley’s death, his son Francis provided some recollections of him that were printed in Edward Peterson, History of Rhode Island (New-York 1853) 118-121. Edward’s great grandson John J. Borie III gathered many more details of his life and old age; these are preserved in typescript among the Brinley Family Papers, Collection 1663, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (hereafter “Brinley Family Papers”).

[2] Copies of Whitehead’s unpublished memoir, in a typewritten transcription entitled “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830” (hereafter “Childhood and youth”), are found at the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, Florida, and the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida; page 16 contains the reference. For some history of the Commercial Bank of New Jersey, see my previous post 004–Birth of a bank. The Whiteheads probably resided in an annex at the rear of the bank building: see 007–Useful pleasures.

[3] “Childhood and youth” 18.

[4] Gertrude Aliph Brinley’s marriage to Rev. Edwin Gilpin of Nova Scotia took place in Newport in June 1827, six months after the wedding of her sister Elizabeth in Perth Amboy to Rev. Job F. Halsey, the recently ordained pastor of Old Tennent Church near Freehold, New Jersey. Frank R. Symmes, in the second edition of his History of the Old Tennent Church (Cranbury, N.J. 1904) 122, related what he deemed “an amusing story” about Elizabeth’s marriage, one “still current” in his day. After preaching on a certain Sabbath in Perth Amboy, Job Halsey was entertained at the home of “two or three” sisters, and soon took to courting one of them by letter. However, being “mistaken in the name,” he found on his next visit that he had been writing to the sister of his intended bride. Halsey nonetheless “accepted the correspondent for his wife, and it is said that he considered the marriage an arrangement of Providence.” The story lacks independent corroboration, but suggests that Catharine could have been the one to whom Halsey thought he had proposed.

[5] Catharine S. Brinley, Newport 31 August 1830, to Gertrude Parker, Brinley Family Papers.

[6] In an early letter sent from Perth Amboy to her Aunt Gertrude, who was sojourning in New York, Catharine wrote, “The trees look beautiful and my arbour has grown so shady that not a bit of sun can get into it.” Catharine S. Brinley, Perth Amboy (no date, postmarked 31 July), to Gertrude Parker. Gertrude’s sister Susan Parker, youngest of the three maiden aunts, described the destruction of “Cate’s Willow” by a ferocious gale: “those beautiful limbs, which have so often wave’d in unison to her feelings of joy, or woe, were in an instant wrench’d from the body of the tree, which remains now a topless trunk, calling forth the lamentations of all her companions who have sat under its branches and enjoy’d its shade.” Susan Parker, Perth Amboy (no date, but datable to 5 June 1831), to Gertrude Parker. Cate’s beloved bower must have somewhat revived, for as she later sought medical treatment in the midst of Philadelphia’s “heated pavements” and stifling atmosphere, “enough to kill a horse,” she mused, “How sweet & refreshing our garden must be!” Catharine S. Brinley, Philadelphia 29 May 1835, to Gertrude Parker. All three of these letters are among the Brinley Family Papers.

[7] Catharine S. Brinley, “Isle of Mist” (Newport, R.I.) 29 June 1833, to Gertrude Parker. With this letter Catharine sent “some knickknacks” that, in Newport, she had “continued to collect for the Fair” of St. Peter’s church: “Hand them over to my beloved Margaret, for her table. She & I were to have one together, had I remained, & I feel every bit as much interested that it should be to our credit, as if I were on the spot.” Anxiety about the finances of St. Peter’s or its school troubled her, even while under a doctor’s care in Philadelphia: “What is to be done about the Fair? I wish the gentleman would take our situations into consideration & fall upon some method of paying the debt at the Bank, & let us work it out in our jogging way, which tho’ slow is sure, it would be a great relief to me, if not to all of us.” Catharine S. Brinley, Philadelphia 29 May 1835, to Gertrude Parker. The “gentleman” in question may have been Matthias Bruen, on whom see note 11. Both letters are found in the Brinley Family Papers.

[8] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 18 February 1834, to Thomas N. Stanford. Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers, MC 608, Special Collections and University Archives, Alexander Library, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.

[9] Catharine S. Brinley, Newport 31 August 1830, to Gertrude Parker, Brinley Family Papers.

[10] Catharine was then around 30 years old, while Van Buren was 50 and widowed for more than a decade. On learning that during the Massachusetts leg of his tour the President’s health had dramatically worsened, Cate wrote teasingly of a sudden revival of her prospects: “Van Buren will certainly be [?] next President. He is a Widower looking out for a wife &–a span of horses–who knows?–Would you like to ride in my coach?–Oh nonsense!” Catharine S. Brinley, “Isle of Mist” (Newport, R.I.) 29 June 1833, to Gertrude Parker, Brinley Family Papers. In fact, Van Buren would not succeed to the Presidency for another four years.

[11] Whitehead’s father had, around this time, tendered his resignation from the post of cashier at the Commercial Bank. Frank Brinley conceived the notion of getting his own father appointed, but wealthy director Matthias Bruen, who had largely taken control of the bank’s affairs, would not offer compensation sufficient to support him. Francis W. Brinley, Perth Amboy 23 June 1834, to James Parker. James Parker Papers, Ac. 719, Special Collections and University Archives, Alexander Library, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. While Frank saw to Edward Brinley and his wife’s removal from Newport to Perth Amboy, “poor Kate” was, according to a cousin, “grieving at the situation of her Father & family … It is indeed a sad thing when a house is divided against itself.” Gertrude Parker, Kipps Bay, N.Y., 27 September 1834, to Elizabeth Parker Halsey, Brinley Family Papers.

[12] “Childhood and youth” 35.

[13] “Childhood and youth” 36.

[14] At the end of 1835, Joseph Togno published a “medical statistical report” of his deaf subjects treated, and wholly or partially cured. Of 130 patients, he claimed 70% were “completely cured” or “greatly improved.” Those “greatly improved, but who discontinued before the treatment was completed,” accounted for most of the remainder. Among the patients, whom the report identifies by their initials and residences, the nearest match for Catharine Brinley is one “Miss B.” a resident of Philadelphia who had been deaf for three years and was “yet under treatment” at the time of publication. Catherine may have given her residence as Philadelphia, for while under Togno’s care in May she boarded with a “Miss Bridges” (a contemporary directory lists her as Mrs. Bridgett) on Spruce Street. But several patients from New Jersey are on the list, while others, residing in places as far afield as New Orleans, Jamaica and France, must likewise have had lodging in town. Catharine traveled to Nova Scotia that summer, against the advice of Samuel Jackson, a distinguished Philadelphia doctor and professor of medicine. J. Togno, Annual medical statistical report of Dr. J. Togno’s infirmary for the cure of deafness, from 1834 to 1835 (Philadelphia 1835) 11-16; Desilver’s Philadelphia directory and stranger’s guide, for 1835 & 36 (Philadelphia 1835) 37; Catharine S. Brinley, Philadelphia 25 and 29 May 1835, to Gertrude Parker, Brinley Family Papers; Cortlandt Parker, New Brunswick, N.J., 20 June 1835, to Margaret E. Whitehead, Parker Family Papers, Manuscript Group 18, Box 6/13, New Jersey Historical Society.

[15] Togno’s methods apparently included forcing air or liquid through the Eustachian tube between the ear and nose. In Catharine’s case, which Dr. Samuel Jackson agreed was a delicate one, Togno postponed the procedure if the weather was “too dubious & uncertain.” Although Catharine wrote assuringly that “these operations … are nothing when you come to see what they are when performed by skillful physicians,” she was not overly confident “as to the result of all these to do’s, but I think it right to try all safe means, for though the time may be afar off, yet who knows but the means will be blessed in the end?” The Corsican-born Togno, however, ran afoul of the Censors of Philadelphia’s College of Physicians for making public claims without specifying any “mode of treatment,” and eventually exchanged his medical instruments for the tools of the winegrower, founding an unsuccessful “Model Vine-dresser School” outside Wilmington, North Carolina. Critics dubbed it “Dr. Togno’s Folly.” Catharine S. Brinley, Philadelphia 29 May 1835, to Gertrude Parker, Brinley Family Papers; Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Centennial volume (Philadelphia 1887) 135-136; Joseph Togno, M.D., Dicôteaux, near Wilmington, to Charles L. Fleischmann, printed in The American polytechnic journal 1:5 (May 1853) 316-318, reprinted in “Joseph Togno’s lament,” The western horticultural review 3:10 (July 1853) 477-480; Clarence Gohdes, Scuppernong. North Carolina’s grape and its wines (Durham, N.C. 1982) 19-22; Thomas Pinney, A history of wine in America. From the beginnings to Prohibition (University of California Press 1989) 223. For suspicions surrounding Togno’s Philadelphia practice, see the experience of Virginia and Nicholas Trist as related in Hannah Joyner, From pity to pride. Growing up deaf in the Old South (Washington 2004) 29-32.

[16] Whitehead’s albums are now held by the Key West Art & Historical Society. For some account of these volumes see my previous post 037–The parting hour.

[17] William A. Whitehead, Contributions to the early history of Perth Amboy and adjoining country, with sketches of men and events in New Jersey during the provincial era (New York 1856) 255 and 259. Catharine’s view of the governor’s mansion (Proprietary House) illustrates my previous post 006–A nest of families.

[18] “Childhood and youth” 23. Communication between Key West and the mainland was unreliable at best. As late as 1835, Cate was disappointed to learn that William and Margaret Whitehead were not receiving her letters: “the irregularity of the mail is provoking,” she wrote. Catharine S. Brinley, Philadelphia 29 May 1835, to Gertrude Parker, Brinley Family Papers. On the “regular irregularity” of Key West’s mail service, see my previous post 043–Together apart.