“LIFE to him seemed hollow, and existence but a burden.” So heavy was the gloom that descended upon poor Tom Sawyer, before his inborn cleverness got other boys believing that to whitewash thirty yards of fence was anything but drudgery.

Facing a similar task, William A. Whitehead seems to have found nothing about life burdensome. “Nor was it thought derogatory in the least” to whitewash the new wood enclosure of St. Peter’s churchyard. Plans were made for “a strong and handsome fence” before the parish was to host the yearly Protestant Episcopal convention, but it was not erected until after the delegates had departed for home. Therefore, fifteen-year-old William could take his time with brush and paint, and as he worked alongside his friend James Parker there was small temptation to farm the labor out to the town’s more gullible boys, if such an idea even occurred to him.1

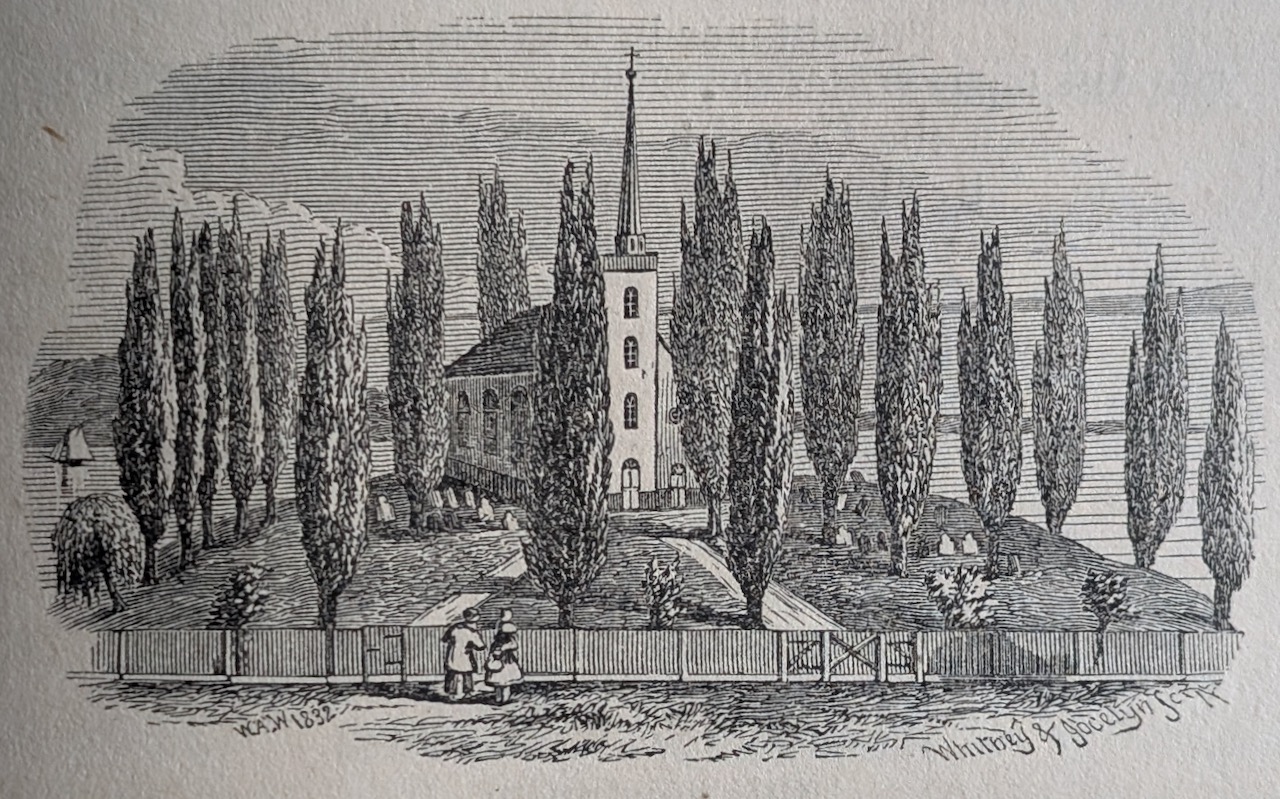

Young Whitehead would pause from the task at times, to gaze into the churchyard at lowly brown monuments dotting the grounds, some tilting this way or that, beneath a canopy of stately poplar trees. These stones marked the graves of Perth Amboy faithful who, having worshipped within the walls of their simple sanctuary “crowning the beautiful knoll that overlooks the waters of the bay,” were one day “borne from the inner congregation to swell the one without.”2

Rector James Chapman had been energetic in soliciting funds to repair and beautify his church before the convention, and declared himself highly satisfied with the results. The building, more than a century old, “looks now like a new edifice.”3 The parsonage house, too, was freshly painted. And newly installed in the chancel wall was a sumptuous marble plaque, honoring the early benefactors who had donated the lots occupied by church and graveyard, and other gifts besides. Ever since he became rector sixteen years before, said Chapman, the placing of this remembrance had been “one of my first wishes.”4

Four names graced the tablet: George Willocks with his wife Margaret, the daughter of Thomas Rudyard, who induced her husband to donate land for a church and cemetery, and to bequeath their house for a parsonage; followed by Thomas Gordon and John Harrison, whose generosity supplied much of the remainder.5

It’s presumed that all four were interred in the churchyard of St. Peter’s, but the grave of only one of them was marked in Whitehead’s time, by a substantial ledger stone lying just beyond the crest of the hill overlooking Raritan Bay. For the meaning of the words incised on it Whitehead had to rely on the Reverend Chapman, but it must have captured his interest, being nearly coeval with the church itself.

This was the gravestone of Thomas Gordon, whose career as a landowner and officer of the province of East New Jersey so intrigued and inspired Whitehead that he would one day pronounce it “sufficient reward to rescue from oblivion some of the incidents in the life of one so intimately connected with the early history of the province.”6

Who was this man whose life Whitehead found so enthralling? A younger son of Robert Gordon of Straloch, 6th Laird of Pitlurg, and his wife Catherine Burnett,7 Thomas Gordon spent his first thirty odd years in his native Scotland. But Whitehead had little information about his life before, barred through primogeniture from inheriting his father’s estates and title, he joined in the creation of a landed aristocracy in America.8

In October 1684, Gordon in his words “did import” into the province of East New Jersey “himself, wife, four children and seven servants,”9 and a year later, as he recalled in a letter to a correspondent in Edinburgh, “I and my Servants came here to the Woods, and 8 dayes thereafter my Wife and Children came also….”10 The “Woods” referred to extended either side of a tributary called Cedar Brook, in the vicinity of modern Plainfield, where Thomas and wife Hellen found themselves in the midst of other Scots householders, including a brother and a cousin of Thomas. “There are 8 of us settled here,” he wrote, each “within half a mile or a mile of another….” The adjacent area would come to be known as Scotch Plains.11

Gordon’s 350-acre farmstead on Cedar Brook is just one indication that, if a frontiersman, he was not one of slender means. Prior to leaving Scotland he had bought one-twentieth of a proprietary share in East Jersey. Further acquisitions after his arrival “placed him among those most deeply interested in its soil.”12

Nor did his several holdings keep him from full participation in affairs at the provincial capital. The Cedar Brook settlement was, he judged, “about ten miles from the Town of New Perth, or Amboy-point, so that I can go and come in a day, either on foot or horseback….” He served on the board of resident proprietors there from its inception, and rapidly added several town lots in Amboy to his country properties.13

Three months after settling at Cedar Brook, Gordon wrote in gratitude: “myself and Wife, and Children, and Servants have been and are still in good health, which God continue….” The following two years increased his blessings but ultimately, as Whitehead noted, “His prayer was not granted.” Hellen, his wife of ten years, died in 1687 at age 27, leaving Thomas the mournful duty of interring her, with four of her offspring, in Perth Amboy’s public burial ground.14 The epitaph, “of a very antiquated character” to Whitehead’s eyes, and among the earliest dated inscriptions in New Jersey, ended with a eulogy in verse:

CALM WAS HER DEATH

WEL ORDERED HER LIFE

A PIOUS MOTHER

AND A LOVING WIFE

HER OFSPRING SIX

OF WHICH 4 HERE DO LIE

THER SOULS IN HEAVEN

WI HERS DO REST ON HIGH

Below these lines were carved the familiar mortality emblems: a death’s head, crossbones, and an hourglass “rudely delineated.”15

Through a second marriage to Janet Mudie, daughter of another proprietor, Gordon’s stake in the province grew still greater, and in 1692 he was named deputy secretary and register of the board, while its chief secretary, London merchant William Dockwra, continued to reside in England. This was only the first of a succession of offices Gordon would hold in the governments of East New Jersey and New Jersey tout court.16 But Gordon and his party found themselves forever at odds with towns and factions that contested the control of land distribution, taxes and rents, by claiming earlier, nonproprietary title to the lands they built and farmed on.

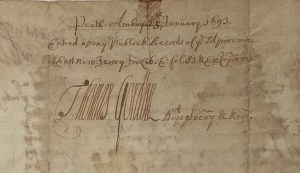

In doubt as to the desirability of having the government of a province fast becoming ungovernable, the East Jersey board late in 1695 dispatched Gordon to England to forge a consensus with the proprietors there.17 Scrutiny of the era’s documentary evidence made Whitehead aware of a draft of the instructions Gordon carried with him to London, which presaged the eventual surrender of the proprietors’ claim to govern: “if the people prove obstinat in refuseing to support the government & defraying the public charge,” it read, “We are of opinion that the proprs thro it up, upon the best terms with the Crown as they can.” In a concluding paragraph, apparently left out of the final version, it was urged that if Gordon were appointed secretary–“an office of great trust & small profits”–£50-60 a year would be saved, as he had offered “to write all the public writings gratis….”18

Out of that seventeen-month London sojourn developed a campaign to dislodge William Dockwra from the position of secretary and install Gordon in his place, which was finally achieved at the end of 1702.19 But in the intervening years far more serious machinations had gripped the New Jersey scene. Governor Andrew Hamilton’s removal, on the grounds of his Scottish birth, was fueling fierce resistance to the man who succeeded him, Jeremiah Basse.20

Both Gordon and Willocks cooperated in the struggle of wealthy proprietor Lewis Morris to refuse legitimacy and funding to Basse’s administration. The three were indicted by a grand jury “for a breach of the Laws of this Province,”21 but their intrigues were ultimately rewarded: Basse’s perceived failure to defend Perth Amboy’s rights as a free port discredited him further, so that within a year Hamilton was returned to the governorship.

Convinced that proprietary rule profited neither the proprietors nor the people, Lewis Morris spearheaded a formal surrender of government to Queen Anne by both the West and East Jersey boards, which however retained their claims to ownership of the soil. Henceforth, New Jersey would be a unified, royal province, having a single governor’s council and general assembly with equal representation from both the Jerseys. The council and assembly would meet alternately in the western and eastern capitals, Burlington and Perth Amboy.22

Queen Anne’s decision to appoint the New York governor, her cousin Edward Hyde, Viscount Cornbury, to preside likewise over New Jersey posed a serious obstacle to the efforts of Morris, Willocks, Gordon and their fellows to shape the province’s future, and to safeguard their own interests in it. Many policies of Governor Cornbury, who arrived in Perth Amboy to proclaim his authority in 1703, were designed to rein in the recalcitrant province, and bring it more firmly under imperial control.

Gordon, as Middlesex County high sheriff, a role assigned him at Morris’s urging, was accused of rigging the first assembly election by choosing a polling place highly inconvenient to those expected to vote against the proprietary interests. When balloting still came out against the proprietors’ side, it was charged that Gordon “multiply’d Tricks, upon Tricks, till at last barefac’d he made ye returne contrary to the choice of the Country.”23

Despite Morris’s and others’ best efforts, proprietary claims proved far from secure, and in 1705 Thomas Gordon, as register and recorder, became a target of the governor’s ire for declining to hand over to former governor Basse, now Cornbury’s secretary, “ye Public Bookes Records papers &c. in his hands”. He was arrested, then released on £2,000 bail. Only after unsuccessful petitions from Morris and the board, and Gordon’s appearance at an Assembly hearing in which Cornbury “very much threatned [sic] & abused” him, were the records surrendered.

Thomas Gordon was to catalog many further abuses at the hands of the governor and his party, as when he was suspended without cause from practicing law, “to ye great Loss & ruin of himselfe and numerous family (having a wife & seaven small children & no other way to maintain them).” Eventually Cornbury’s successor would reinstate him to the bar.

On another occasion, not three days after the assembly at Burlington chose him as speaker, Gordon was arrested on a charge the Supreme Court had already dismissed. Refused a writ of habeas corpus by a judge of that court, he was forced to apply to the judge’s son, the only attorney available, “for which he paid thirtie Shillings notwithstanding he Drawed ye Writs himselfe….”

Then there was Cornbury’s response to the charge, leveled at his ally Peter Sonmans, of having absconded with the records of the East Jersey board: the governor rejoined that “The Records are not carried out of the Eastern Division unless it be those which Tho. Gordon has imbezled….”24

Gordon’s safety from persecution–along with his freedom from the sheriff’s custody–seems to have remained at risk until 1710, the year that brought to the governorship of New Jersey and New York a fellow Scotsman, Colonel Robert Hunter, whose aide-de-camp and trusted advisor was none other than Lewis Morris. Gordon’s subsequent return to the council didn’t immunize him from partisan attacks, but he no longer faced the same threats to his liberty or livelihood. In 1714, the record books taken from the proprietors were returned to his care, although he relinquished them and the role of register and secretary a year later, Hunter in the meantime having named him New Jersey attorney general.25

The unpleasant events of Gordon’s long career showed “how much of evil may result from mal-administration of the best-devised schemes”; it was deeply regrettable that power should then have been placed in “such profligate hands….”26 These were the comments of Whitehead, but the “profligate hands” belonged to Cornbury, on whom the nearest thing to a compliment Whitehead would venture was that he owed his appointment as governor “mainly to his relationship to the Queen.”27 The verdict of the New Jersey historian has been echoed by almost every other since: Cornbury’s six-year rule over New Jersey was arbitrary, corrupt, tyrannical and almost universally unpopular.28

While there’s ample evidence of the governor’s high-handedness, it must be conceded that Cornbury was sent to administer a territory riven by deep-rooted political and sectarian prejudices, where profound personal enmities held sway. In an era of disloyal opposition, what must have seemed at times a “war of all against all” made it, and makes it, a daunting task to separate truth from falsehood.29 The most minute analysis of this aspect of the era calls it a “high age of calumny,” of which we have no better illustration than the charge that it was Lord Cornbury’s “unfortunate Custom” to dress in public as a woman.30

As with the general condemnations of his governance, this specific allegation has been often repeated. Its origins, contemporary with Cornbury’s rule but grounded in the intrigues of his enemies, require no rehearsing. But it’s here worthy of note that, while in most instances the salacious rumor represented just a single facet of a wide-ranging campaign for the governor’s removal, one of its effects could not fail to invite the attention of William Whitehead.

An Anglican missionary, who appeared to Whitehead “to have been a truly zealous and sincere clergyman of the Church,” was vocal in his condemnation of the chief magistrate’s alleged cross-dressing. Cornbury’s persecution of him was purportedly relentless, until the good cleric, thinking it the better part of valor to escape “the tyranny of a dissolute governor,” took ship for England and was lost at sea.31 In perceiving it as an outrage to religion, Whitehead thus gave to the cross-dressing legend not only full credit, but a currency it might not otherwise have had.

Thomas Gordon breathed his last in April of 1722, the year St. Peter’s church was dedicated. His grave, in the burying ground that was partly his gift, received a smooth slab of sandstone bearing an extravagant Latin inscription. Ably composed if awkwardly cut, it extolled his service as provincial secretary–in which position “he exerted his best abilities in behalf of the Councils of the State”–and his piety, love of life and calm acceptance of death.32

“Too often,” Whitehead allowed, “the partiality of friends renders the monumental inscription but poor authority for the general character of the dead,” but from extensive research into Gordon’s career–its extent, he admitted, perhaps “disproportioned to the result”–Whitehead had formed “a high opinion of his character and abilities” and could see no reason to question this synopsis in stone.33 It’s likely that he also approved of the concluding encomium, albeit filtered through the English of the Reverend Chapman: “He lived as long as he desired–as long as the fates appointed–thus neither was life burdensome, nor death bitter.”34

Gordon’s stone and its epitaph conveyed the devotion of his second wife, including her wish to be buried beside him, but whether this wish was fulfilled is not recorded. Whitehead would one day pay his own tribute, not to Thomas Gordon or his widow but to Hellen, Gordon’s first wife, by arranging for the rescue of her larger, heftier stone, lying forgotten in an abandoned burying ground a few blocks away, and seeing to its placement next to her husband’s.35

Was Whitehead deceived in his unreservedly favorable assessment of Thomas Gordon? Or, in view of subsequent historians’ reliance on Whitehead and his inescapable influence in the field, should he instead be faulted for painting over the less savory features of Gordon’s many-hued career? The charge could hold if he were shown to have ignored, obscured or concealed their traces, but his approach seems to have been the contrary: to gather and make known, without any expectation of reward, all that could be found, and found relevant, for this tempestuous period of New Jersey’s history.

As in other cases, Whitehead may have shown more indulgence to the proprietors’ prerogatives than would suit a more democratic age, including perhaps his own. And he was certainly susceptible to more conservative influences, emanating from his identification with the Episcopal church, and with a family to whose proprietary past he was inexorably drawn by interest and affection.

These considerations may not acquit him of handling one so privileged and combative as Thomas Gordon with such sympathy. But it should be remembered that to Gordon as much as to anyone was due that church on the knoll, with the view of the bay that visitors to Whitehead’s own grave would someday enjoy.

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.12.15

[1] There’s a slight discrepancy in the sources about the year the fence was painted. Whitehead recorded its being erected in 1824, and recalled whitewashing it “in or about 1826.” William A. Whitehead, Contributions to the early history of Perth Amboy and adjoining country, with sketches of men and events in New Jersey during the provincial era (New York 1856; hereafter “Whitehead, Contributions”) 237; “Childhood and youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, Florida, transcription, page 20. But in 1825, when the diocesan convention met at St. Peter’s, rector James Chapman reported that the fence was “in progress.” Journal of the proceedings of the forty-second annual convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the state of New-Jersey, held in St. Peter’s Church, city of Perth-Amboy, on the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth days of May, 1825 (New-Brunswick 1825; hereafter “Journal of the proceedings”) 16. Immediately after the convention ended, Chapman wrote to his friend Thomas N. Stanford, “We hope soon to have a new fence around the yard, as the principal part of the materials are on the ground.” James Chapman, Perth Amboy 27 May 1825, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers, MC 608, Special Collections and University Archives, Alexander Library, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. (hereafter “Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers”).

[2] Whitehead, Contributions 219-220.

[3] Journal of the proceedings 16. “The appearance of the Church since its painting & repairs has excited the admiration of all who attended the Convention.” James Chapman, Perth Amboy 27 May 1825, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers.

[4] James Chapman, Perth Amboy 27 May 1825, to Thomas N. Stanford, Thomas Naylor Stanford Papers. The cost of the tablet was paid out of $40 raised by “the ladies of the congregation” for that purpose: Journal of the proceedings 16. In the month following its dedication, Chapman gave two historical sermons, later expanded as Historical notices of Saint Peter’s Church, in the City of Perth-Amboy, New-Jersey, contained in two discourses delivered in the said Church, June 19th and 26th, 1825, shortly after the erection of a marble tablet in the east wall of the Church, in memory of the first benefactors of the same; with some additions (Elizabeth-Town 1830; hereafter “Chapman, Historical notices”). Relocated several times, the tablet now hangs in the north wall of the present church. See W. Northey Jones, The history of St. Peter’s church in Perth Amboy New Jersey … ([New York] 1924; hereafter “Jones, History of St. Peter’s”) 96.

[5] Whitehead, Contributions 67, 82, 86, 218; Jones, History of St. Peter’s 42-43, 297. On the basis of early records, Whitehead counted John Barclay among the congregation’s “liberal benefactors,” and thought his omission from the plaque “unfortunate.” Whitehead, Contributions 218 n.21. On Barclay’s various services to the province see ibid. 42-43.

[6] Whitehead, Contributions 66. Jones, History of St. Peter’s 274, asserts that Thomas Gordon was the first person interred in the churchyard, but his having reserved a plot for himself near the grave of his daughter Isabella indicates a prior interment: see Edward J. Raser, comp. New Jersey graveyard and gravestone inscription locators. Middlesex County (New Brunswick, N.J. 2018; hereafter “Raser, Middlesex County”) 164. In Inscriptions on monumental stones of dates prior to 1800 at Perth Amboy, N. J. ([1846], manuscript bound together with a later compilation of Woodbridge and Piscataway inscriptions, New Jersey Historical Society, call number N 929.5 M58; hereafter “W. A. Whitehead, Inscriptions”), Whitehead merely states that the ground was first used “about 1720.” No written records of eighteenth-century burials at St. Peter’s are known to survive.

[7] The epitaph of Thomas Gordon’s wife calls her “MRS HELLEN GORDON | SPOUSE TO THOMAS GORDON | OF THE FAMILIE OF STRA|LOCH IN SCOTLAND.” Whitehead understood Hellen to be “of the family of Stralogh [sic],” but that lineage was clearly Thomas’s. His own gravestone inscription, however, bespeaks another inheritance at least as old: “QUI FAMILIA PR|ISCA DE PITLURG IN SCOTIA OR|TUS PROSAPIA SI FAS ESSET POT|UIT GLORIARI”; in Chapman’s translation, “Who, being descended from an ancient family of Pitlochie, in Scotland, could have gloried, had that been proper, in his extraction.” Whitehead’s understanding of the East Jersey colonial project was above all filtered through the book of George Scot of Pitlochie, which he reissued in modern dress; on this work, and Whitehead’s reedition of it, see my earlier post 053–Scot’s Model. Its influence may have led Whitehead to follow Chapman’s misidentification of Gordon’s stated roots in Pitlurg, Banffshire, with Scot’s origins in Pitlochie, Fife. See Whitehead, Contributions 60, 65; William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 2. 1687-1703 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 2. Newark 1881. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 2”) 106 n.1. More than 100 miles separate the localities of Pitlurg and Pitlochie, but confusing them is a mistake I have made myself: see my earlier post 035–Renaissance man at note 2. Alice Airey of the National Library of Scotland very kindly helped me to clarify Gordon’s origins.

[8] In 1713, Monmouth County minister Alexander Innes swore to Gordon’s good character: that he had been “born in the same neighbourhood” as himself, was “a Person of an University Education,” and “for Learning, honesty and integrity of Life is inferiour to no Lay man in the Province where he Lives….” William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 4. Administrations of Governor Robert Hunter and President Lewis Morris. 1709-1720 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 4. Newark 1882. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 4”) 176-178. Any confirmation of a university education has yet to be found. A deed in the year of his emigration names Gordon “servitor to my Lord High Chancellour of Scotland,” the 1st Earl of Aberdeen. I am indebted to Derrick Johnstone for this reference and for earlier evidence of Gordon’s commercial and judicial activities in and near Edinburgh, as a merchant’s apprentice, a merchant, an officer of the Court of Session, and a recruiter of emigrants “unto the Province of New-East-Jersy in America”: see the entry and references at East Jersey bound. Scottish emigrants to East New Jersey in the 1680s. Possessing scant information about “a Thomas Gordon, ‘writer in Edinburgh,’” Whitehead couldn’t conclusively identify him with the emigrant. Whitehead, Contributions 61 n.5.

[9] The minutes of the Board of Proprietors of the Eastern Division of New Jersey from 1685 to 1705 (Perth Amboy, N.J. 1949; hereafter “Minutes of the Board of Proprietors”) 73, minutes of 9 July 1685; cf. Whitehead, Contributions 62. Joseph Wagner concluded that Gordon, his family and indentured servants were among 160 passengers leaving 11 July 1684 from Leith aboard the English ship Shield, Daniel Towes master. The vessel sailed up Chesapeake Bay to take on tobacco for the return journey, and was “disabled” in Maryland, whence the Gordons and others had to complete their journey to East Jersey by other means. Joseph Wagner, “The Scottish colonising voyages to Carolina and East New Jersey in the 1680s,” The northern mariner/Le marin du nord 30:2 (Summer 2020) (155-166) 162-163; Derrick Johnstone, Scots emigrants to East Jersey, 1682-1702: motivations and outcomes (M.Phil. thesis, University of Glasgow, 2025) 27; cf. Whitehead, Contributions 61.

[10] Thomas Gordon, 16 February 1686 (o.s. 1685), to George Alexander, in [George Scot,] The model of the government of the province of East-New-Jersey in America; and encouragements for such as designs to be concerned there. Published for information of such as are desirous to be interested in that place (Edinburgh 1685; hereafter “Scot, Model”) 254-258; repr. in William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary governments: a narrative of events connected with the settlement and progress of the province, until the surrender of the government to the Crown in 1702 [1703] (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1. Hereafter “Whitehead, East Jersey”) ([New York] 18461) 326-327, (Newark 18752) 467-468; cf. Whitehead, Contributions 62.

[11] Another emigrant’s epistle attests to this nucleus of Scots settlement in East Jersey: “I went out to the Woods to the Land we had pitched upon, with several others of our Countreymen such as Tho: Gordon, and Mr. Char: [Charles] his Brother, Brothers to the Laird of Straloch….” John Forbes, Perth Amboy 18 March 1686 (o.s. 1685), to James Elphingston, in Scot, Model 241; repr. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 320, (18752) 460.

[12] Whitehead, Contributions 64. On arriving at Cedar Brook, Gordon had “put up a Wigwam in 24 hours, which served us till we put up a better house,” with a plan “to build a better House and larger” after building “upon my lot at New Perth.” Thomas Gordon, 16 February 1686 (o.s. 1685), to George Alexander: Scot, Model 255-256; repr. Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 326, (18752) 467. He seems to have signed over his initial “improvements” at Cedar Brook (where he “formerly dwelt”) to John Barclay: Minutes of the Board of Proprietors 122, minutes of 11 February 1686 (o.s. 1685).

[13] Within a year of his arrival, the board granted Gordon “a front lot at Amboy”: Minutes of the Board of Proprietors 87, minutes of 10 September 1685. Others of his town lots are indicated on the “Map of Perth Amboy showing the manner in which it was originally laid out and located,” in Whitehead, Contributions facing 9.

[14] Hellen’s death–and perhaps the deaths of her children–occurred during what was described as “a very sickly year”: Andrew Hamilton, Perth Amboy 26 May 1688, to William Dockwra, in NJA ser. 1, 2:(27-34) 29.

[15] Whitehead, Contributions 63 (whose version of the epitaph omits the words “MARRIED 10 | YEARS”); W. A. Whitehead, Inscriptions. For the old public burying ground on State Street, see Whitehead, Contributions 240-241; Raser, Middlesex County 160-161.

[16] Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 133, (18752) 188; cf. Whitehead, Contributions 14-15. In 1696, Gordon became executor of his father-in-law David Mudie, whose wealth Whitehead inferred was “such as the majority of the settlers did not enjoy.” Whitehead, Contributions 48; cf. William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 21. Calendar of records in the office of the Secretary of State. 1664-1703 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 21. Paterson 1899) 237; Minutes of the Board of Proprietors 222 and 240, minutes of 10 April 1696 and 20 December 1700.

[17] “Instructions of the East Jersey Proprietors to Thomas Gordon,” NJA ser. 1, 2:106-113. Attempts to assert proprietary authority also led Gordon to make three trips to New York to litigate the case against Jeffrey Jones, holder of a nonproprietary patent from former governor Richard Nicolls. The board would eventually empower Gordon to commence ejectment proceedings against any patentees who had failed to build on or settle lands allotted to them. Minutes of the Board of Proprietors 216-219, 249, 251, minutes of 21 October and 11 November 1695, 30 March and 14 August 1701.

[18] NJA ser. 1, 2:112-113 and 113 n.1. Whitehead’s papers preserve his copy of the original draft, which he found in the collections of the New-York Historical Society: William A. Whitehead Papers, Manuscript Group 177, New Jersey Historical Society. Box 2/4. See Whitehead, East Jersey (18752) 193-194 n.4.

[19] Whitehead, Contributions 15, 65; cf. Whitehead, East Jersey (18752) 217 n.2.

[20] For Hamilton’s dismissal, see NJA ser. 1, 2:176-177; Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 137-138, (18752) 194-195.

[21] See William A. Whitehead, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 3. Administrations of Lord Cornbury and Lovelace, and of Lieutenant Governor Ingoldesby (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 3. Newark 1881. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 3”) 481 and, for the details of Morris’s campaign of resistance, NJA ser. 1, 3:476-496. Cf. Eugene R. Sheridan, ed. The papers of Lewis Morris (3 vols. Newark 1991-1993; hereafter “Sheridan, Papers of Lewis Morris”) 1:10.

[22] For the surrender of government to the Crown, see Whitehead, East Jersey (18461) 151-155, (18752) 218-226. Gordon was among the signers of the surrender for East Jersey: NJA, ser. 1, 2:459.

[23] “Communication from Colonel Robert Quary to the Lords of Trade, about New Jersey affairs,” NJA ser. 1, 3:(13-22) 14-15; cf. NJA ser. 1, 3:135, 195, 392-393, 400.

[24] “The case of Thomas Gordon Esqr.” in William A. Whitehead, ed. An analytical index to the colonial documents of New Jersey, in the state paper offices of England, compiled by Henry Stevens (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 5. New York 1858. Hereafter “Whitehead, Analytical index”) 79-80; NJA ser. 1, 4:75-77. See also see Whitehead, Contributions 66-67; Whitehead, Analytical index 77; NJA ser. 1, 3:176-177, 185, 189, 500-501; NJA ser. 1, 4:40.

[25] Frederick W. Ricord and William Nelson, edd. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 13. Journal of the Governor and Council. Vol. I. 1682-1714 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 13. Trenton 1890) 534, journal entry of 4 March 1714 (o.s. 1713); Frederick W. Ricord and William Nelson, edd. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 14. Journal of the Governor and Council. Vol. II. 1715-1738 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 14. Trenton 1890) 2-3, journal entry of 7 November 1715; NJA ser. 1, 4:208-209; see also “Arguments against Peter Sonmans,” in Sheridan, Papers of Lewis Morris 1:(331-358) 336. Gordon had been commissioned attorney general after his return from England in 1699, but this was a new appointment; see Whitehead, Contributions 64; Whitehead, East Jersey (18752) 209 n.1, 212 n.1, 351.

[26] Whitehead, Contributions 211.

[27] [William A. Whitehead, ed.] The papers of Lewis Morris, governor of the Province of New Jersey, from 1738 to 1746 (New-York 1852; hereafter “Whitehead, Papers of Lewis Morris”) 11. Elsewhere Whitehead refers to Cornbury’s as an “unpopular and disorganizing administration”: Whitehead, Contributions 149.

[28] Whitehead’s contemporary George Bancroft declared that Lord Cornbury “had every vice of character necessary to discipline a colony into self-reliance and resistance,” an assessment that must have exerted substantial influence on future historians. George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the discovery of the American continent 3 (Boston 18416) 60.

[29] Among the attacks on Gordon were charges that he had “Kept a Taphouse at Amboy” and that, although a “poor ignorant insignificant fellow” who “has no Estate,” he was made treasurer of the province as “a Tool to serve ym in all affairs.” NJA ser. 1, 3:393; NJA ser. 1, 4:157-158. For an anonymous refutation (Whitehead judged that it was probably written by Lewis Morris) of the latter claim, see NJA ser. 1, 4:165 and cf. 161 n.1. See also Gordon’s defense against the “Scandalous Character” imputed to him by Jacob Henderson, a Church of England missionary to Pennsylvania, in NJA ser. 1, 4:176-182.

[30] Patricia U. Bonomi, The Lord Cornbury scandal. The politics of reputation in British America (Chapel Hill, N.C., and London) 99 and passim. Bonomi ibid. 158-163 analyzes four contemporary letters making this accusation; Whitehead was aware of at least two of them: see Whitehead, Papers of Lewis Morris 321-322; Whitehead, Contributions 214, 216 n.13; Whitehead, Analytical index 64; NJA ser. 1, 3:284.

[31] Whitehead, Contributions 213-215.

[32] “NAM A SECRETIS HUJUS PROVIN|CIÆ REIPUBLICÆ EMOLUMENT|UM EX ANIMO RESPICIENS | SENATUI QUOAD POTUIT OPTI|ME CONSULUIT….” I know no publication of the inscription prior to Chapman, Historical notices 26. Chapman’s translation was first published in Whitehead, Contributions 65; cf. 65 n.12.

[33] Although a clergyman (or Thomas himself) was more likely to have composed it, the inscription credits Janet Gordon with having this monument made to her husband, “IN MEMORIAM CUJUS | UXOR MÆRENS QUÆ HIC | ETIUM [sic] CONDI EXPETIT HOC | QUALECUNQUE SIT PONI | CURAVIT.” Whitehead saw “no cause to doubt the justness of the terms in which his widow has transmitted to us the memory of Thomas Gordon.” Whitehead, Contributions 66.

[34] “VIXIT DUM VOLU|IT DUM FATA VOLEBANT | SIC NEC VITA GRAVIS MORS | NEC ACERBA FUIT.” These lines are in elegiac meter, forming a distich that is missing its first foot. The carver originally inscribed ACERBUS, and while the necessary correction was made the mistake is more prominent.

[35] Miniature pen-and-ink drawings in one of Whitehead’s early scrapbooks (its title page bears the dates 1828-29) suggest a precocious interest in the preservation of the Gordon gravestones. Wm. A. Whitehead, Scrap Book No. 2, Manuscript Group 724, New Jersey Historical Society, Box 2, page 77. Later he adverted to the two stones in a Newark newspaper column, and copied both texts (together with Chapman’s translation of the Latin) into his manuscript of pre-1800 Perth Amboy inscriptions: G. P., [no title], Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 7 June 1849 2:1; W. A. Whitehead, Inscriptions. Hellen Gordon’s stone lay for nearly two centuries in what had been the old public burying ground on State Street. In 1867, the trustees of the Presbyterian church were granted permission to vacate and sell the land, and the removal of remains began to Perth Amboy’s Alpine Cemetery, incorporated in 1862: Raser, Middlesex County 160. On the page in Whitehead, Inscriptions, reproducing Hellen Gordon’s epitaph is a pencilled note in Whitehead’s handwriting: “Had this removed in 1877 & placed along side of her husbands gravestone in St. Peters Church yard.” The date of removal carved into the stone itself is August 1875, while Jones, History of St. Peter’s 274 gives the year as 1876.