FORMED in 1807 to map the nation’s shorelines and chart its coastal waters, the United States Coast Survey was beset for much of its early life by military, political and economic pressures, slowing and sometimes halting the progress of the first scientific agency ever established by the federal government. But the value of its aims or limited achievements was in no way diminished in the eyes of career scientists, or of others who, like William A. Whitehead, professed a “love for Nature and all natural phenomena….”1

Joined to a mathematical disposition and a talent for drawing, this fondness for nature made Whitehead a lifelong enthusiast for the science and art of representing geographical features by the use of ruler, pen and paper. Land surveying, as he recalled of his younger years, was one “among other things which I had taken up and studied by myself….”2 Only once, so far as we know, was he hired and paid to conduct a survey and convert its courses and bearings to lines on a page. The result portrayed a thinly populated island far from his home, whose significance he could then barely discern. Yet the history that would later occupy so much of his spare time, talent and energy had at its very core the drawing of boundaries. Over decades of labor to illuminate the dark corners of that history, Whitehead both relied on and produced a profusion of maps.

The struggle to contain land within borders and assert control over it colored much of the New Jersey history in which Whitehead did his pioneering work. Mapping shorelines and sounding channels were projects essential to the survival and success of the early colonists, but, as elsewhere in the age of empires, the fixing of provincial borders couldn’t proceed without decades, if not centuries, of discord.

Foremost in this chronicle of divisive division, besides the line inconclusively plotted between the two provinces of East and West Jersey, was the one specified in the Duke of York’s initial grant: a straight line, drawn from a point on the Delaware River at the latitude of 41º 40′ North to a point on the Hudson River at 41º North. All land south of this line was to belong to “New Cesarea or New Jersey,” while the province of New York would have all the land north of it. “No terms,” in Whitehead’s view, “could have been used more clearly defining the tract to be conveyed,”3 but with no agreement about the location of the station points on each river, the line itself was fated to be long and bitterly contested.

Whitehead traced the tortured history of this dispute from “behind the scenes,” as he put it, having at his disposal “the correspondence of all the prominent actors on the part of New Jersey….” Priceless though this trove of materials was, and is, Whitehead was assuredly affected by the one-sidedness of his sources. He characterized the actions of New Jersey parties as “entirely honorable and manly,” while the stance of New York was alternately indifferent, intransigent or hostile. He felt he was “reading a new version of the fable of the wolf and the lamb,” when the inhabitants of mighty New York lashed out at their lowly neighbor.4

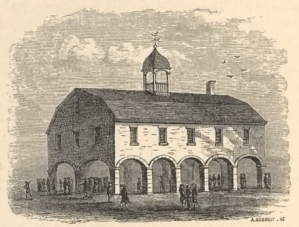

Fifty years from the running of an initial boundary line, which had however failed to secure agreement on both sides,5 a commission was at last organized to adjudicate the opposing claims. Its six worthy members met for the first time on 18 July 1769 in the Royal Exchange, a building standing at the foot of Broad Street in the city of New York.

Among the arbiters was 40-year-old Dutch-born Samuel Holland, Royal Engineer. His cartographic expertise had helped the British to wrest Canada from the French; now, as Surveyor General of the Northern District of North America, he and his survey teams were engaged in the monumental enterprise of mapping the Atlantic coast from Québec south to the Chesapeake.

Holland’s scientific acumen and unshakable resolve had won him admirers on both sides of the Ocean. His name was even used to market maps whose authorship he was apparently compelled to deny. One such production came into Whitehead’s hands. A 1768 London printing of a map Holland had hastily put together using second-hand information, it displayed the web of competing lines with which, over the half-century leading up to the 1769 conference, rival claimants had proposed to settle the boundary between New York and New Jersey.6

Perth Amboy’s James Parker, of the East Jersey Board of Proprietors, appeared to be New Jersey’s chief advocate before the commission. He had assistance and advice from William Alexander, known as Lord Stirling, and other notable New Jersey figures, “though they seem to have been irregular in their attendance….”7

During its deliberations, the commission received new maps and survey data from both sides. Samuel Holland himself set up an astronomical observatory to determine the correct station point on the Hudson. In this, he was aided by the instruments and expertise of Philadelphia’s David Rittenhouse, “a most Impressing Genius,” wrote Holland, “as well in Arts as Sciences & that without any other instructions but by Books.”8

The data collected were combined into “one general map,” which Whitehead regretted he was unable to locate: “From the details it must have contained, it would be a valuable acquisition, could it be found.” In his possession, however, were the field notes from New Jersey’s running of the line, and what appeared to be the sole surviving copy of its final brief, “making, as printed, forty-four folio pages.”9

The New Jersey brief, Whitehead asserted, reviewed “in a masterly manner every pretension” of the opposing side, so that “after a careful examination of its arguments and verification of not a few of its statements by a reference to the original authorities,” the historian was at a loss to explain the commission’s final decree, except that it seemed “based upon no principle save that of accommodation to the claims of New York.”10 The judgment of the commission appeared to Whitehead to pay no heed to New Jersey’s rightful claims, and would ultimately bring about nothing less than a “curtailment of the dimensions of the State….”11

Samuel Holland and one other commissioner, citing “Principles of Justice and Equity,” dissented from the final decree, but only in its placement of the Hudson River station. They said that in their experience the latitudes on older maps were “Several Miles more Southerly” than modern observations found them to be. Holland opted, in “Tenderness therefore to the New Jersey Settlers,” for a more northerly station as “the Least detrimental….”12 But the majority ruling stood. It was eventually confirmed by the two provincial legislatures and, with royal assent, given in 1773, “one hundred and eight years after the grant was received from the Duke of York,” New Jersey’s northern boundary was settled for good.13

Holland, meanwhile, had returned to the coast survey, whose headquarters were moved from Québec to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The survey of Maine’s intricate coast was completed in 1773, and in the same year, if not before, Holland set his sights on a yet more southerly place from which to continue the work.

In September, James Parker sent word to Holland that New Jersey governor William Franklin, hitherto a resident of Burlington in West Jersey, had decided to make his home in the East Jersey capital of Perth Amboy. Holland found this news very gratifying, and wrote back to Parker expressing his desire to become, along with the governor, one of Parker’s neighbors. He would, however, insist on certain particulars:

as the business I am entrusted with requires a house much larger than what I should want for my private use, I beg leave to trouble you with a description of such a one as I should want, viz: a large room to draw my plans in, two smaller, to serve as an office and instrument room; so that there should be at least eight apartments besides a kitchen: as for stables, I should have room for two horses, two cows, and a chaise: a good garden and some fruit trees would make my situation more pleasant. As the gentlemen deputy surveyors must come and draw at my house, it should not be far from houses where they can lodge and board. The Board of Trade allows me £25 sterling per year for house rent; so I should not like to exceed that sum.

If Parker could meet these detailed requirements, Holland wrote,

I shall make Amboy the rendezvous of astronomers and geographers until the Northern District is completed, which includes all the Provinces north of Virginia. … it will take at least six years to finish the whole survey, and after all I shall become a New Jerseyman.14

When Whitehead found this letter of Holland’s, presumably among the papers of its recipient, he learned for the first time of “a survey of a more general and systematic character” than he supposed “had ever been attempted of our coast….” Years later, at Whitehead’s behest, the New Jersey Historical Society’s agent in London, Henry Stevens, would supply abstracts of documents in the State Paper Office showing that there was more to know about Samuel Holland and his New Jersey aspirations.15

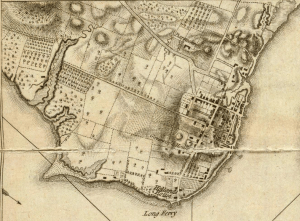

Indeed, a letter to London dated from Perth Amboy on 20 December 1774 showed that Holland had secured his desired accommodations, and had removed from New Hampshire to New Jersey.16 A printed map based on his drawings, which includes an inset “Plan of Amboy, With its Environs, from an Actual Survey,” even purported to show the location of Holland’s house near the wharf at the foot of High Street.

Whatever the precise situation of his new headquarters, it must have seemed to Holland that in Amboy he had attained what, to another correspondent, he declared himself determined to find: “Some place where Retirement, Conveniency & neighbourhood Shall offer, not nearer New York than ten or a Dozen miles.”17

From here, Holland continued to oversee his survey teams in New England, although growing unrest was making work there more difficult. A harsh naval blockade, imposed in response to the December 1773 “Tea Party” in Boston Harbor, left his surveyors “greatly distressed before they could obtain Provisions from Boston….” Holland planned in 1775 for them to reach the Hudson River by summer’s end, confessing that it would be difficult, owing to “the present situation of public Affairs,” but assuring authorities in London that there would be “no material Delay to the Service, as there is much Drawing to be done, which will employ those of my Party fully, who are not surveying.”18

By the end of summer 1775, the state of “public Affairs” in New Jersey had also clearly taken a turn. In September he reported:

… with Difficulty, I equiped One Party, with this I have endeavored to survey the Environs of this Place, presuming that the General Good Opinion which had prevailed in Favor of my Business with all Parties, from its Evident Utility, would have supported it, untill Public Affairs should become more Settled; I have been obliged however to desist somewhat sooner than I expected, & apply entirely to Drawing; of which as I observed in my Last, there is sufficient to employ Us of a long Time.19

Such long employment was not to be. Within two months of writing those words, Holland and his deputies had abandoned Perth Amboy and their work. As Whitehead well imagined, the onset of war prevented the survey’s continuation, and precluded “Capt. Holland’s firm establishment as a Jerseyman.”20 His fidelity to the Crown overcame the desire to find, in the coast survey’s final home or elsewhere in the Jerseys, a place of “Retirement, Conveniency & neighbourhood.” He died in the city of Québec in 1801.

Six years later, a new survey was to take the first few, hesitant steps on its long journey down the coast.

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2025.11.14

[1] “Childhood & youth of W. A. Whitehead 1810-1830,” manuscript volume at the Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, Florida (hereafter “Whitehead, ‘Childhood & youth’”), transcription page 23.

[2] Whitehead, “Childhood & youth,” transcription page 24.

[3] William A. Whitehead, “Northern boundary line: the circumstances leading to the establishment, in 1769, of the northern boundary line between New Jersey and New York. A paper read before the New Jersey Historical Society, May 19, 1859,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society [ser. 1] 8:4 (1859) (157-186; hereafter “Whitehead, ‘Northern boundary line’”) 160.

[4] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 169-170, 172.

[5] For the earlier survey and the tripartite agreement that emerged from it, see Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 163-165.

[6] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 174. As first published by Thomas Jefferys and Robert Sayer of London, the map was entitled The provinces of New York, and New Jersey; with part of Pennsylvania, and the governments of Trois Rivieres, and Montreal: drawn by Capt Holland. Engraved by Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to His Majesty. It bore no date. Whitehead’s guess of “about 1760” as the date of publication was probably nearer to the year of its original compilation. The printed map was advertised for sale in New York newspapers in 1768, and included in Jefferys’s A general topography of North America and the West Indies, published in London in the same year. For Holland’s disavowal of this production, see Thomas Pownall, A topographical description of such parts of North America as are contained in the (annexed) map of the middle British colonies, &c. in North America (London 1776) v and note; Lois Mulkearn, ed. A topographical description of the dominions of the United States of America … by T. Pownall, M.P. (Pittsburgh 1949) 8 and n.3.

[7] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 176 and cf. 179. Alexander, a man “distinguished for his mathematical abilities,” had recently shared with Holland the rare experience of observing the planet Venus pass over the sun’s surface on 3 June 1769. Holland saw the beginning of the transit from L’Île aux Coudres in the St. Lawrence River, while Alexander watched a part of it from his manor near Basking Ridge, New Jersey.

[8] Samuel Holland, Hudson’s River observatory, Lat. 41º 1′ 0″, 8 September 1769, to Frederick Haldimand. The British Library Add. MSS. 21679, f. 68/69. According to Whitehead Rittenhouse “has been called the Newton of America.” Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 178.

[9] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 178-179. The New Jersey agents’ field notes encompassed “about twenty miles, or more than two-fifths of the distance across….”

[10] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 179-180.

[11] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 160.

[12] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 182-183.

[13] Whitehead, “Northern boundary line” 185.

[14] “An old coast survey,” in G. P., “Glimpses of the past in New Jersey, No. X,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 14 April 1842 2:1; hereafter “G. P., ‘An old coast survey’.” The whereabouts of Parker’s letter to Holland, and the original of Holland’s reply, have not been discovered.

[15] Whitehead at first thought it “doubtful if the rendezvous was established at Amboy as purposed….” G. P., “An old coast survey.” For the efforts of Stevens on New Jersey’s behalf, see my earlier post 056–Our man in London.

[16] Samuel Holland, Perth Amboy 20 December 1774, to John Pownall. The National Archives (London) CO 323/29; printed in Frederick W. Ricord and Wm. Nelson, edd. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey. 10. Administration of Governor William Franklin. 1767-1776 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 10. Newark 1886. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 10”) 518-521.

[17] Samuel Holland, Portsmouth (N.H.) 13 June 1774, to Frederick Haldimand. The British Library Add. MSS. 21731, f. 176.

[18] Samuel Holland, Perth Amboy 27 May 1775, to the Earl of Dartmouth. The National Archives (London) CO 5/76; printed in NJA ser. 1, 10:599-600. Cf. William A. Whitehead, ed. An analytical index to the colonial documents of New Jersey, in the state paper offices of England, compiled by Henry Stevens (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 5. New York 1858. Hereafter “Whitehead, Analytical index”) 445.

[19] Samuel Holland, Perth Amboy 20 September 1775, to the Earl of Dartmouth. The National Archives (London) CO 5/76, printed in NJA ser. 1, 10:660-662. Cf. Whitehead, Analytical index 447.

[20] G. P., “An old coast survey.” For what is known of Holland’s last difficult months in Perth Amboy, see Stephen J. Hornsby, Surveyors of empire. Samuel Holland, J. W. F. DesBarres, and the making of The Atlantic Neptune (Montreal 2011) 171-176.