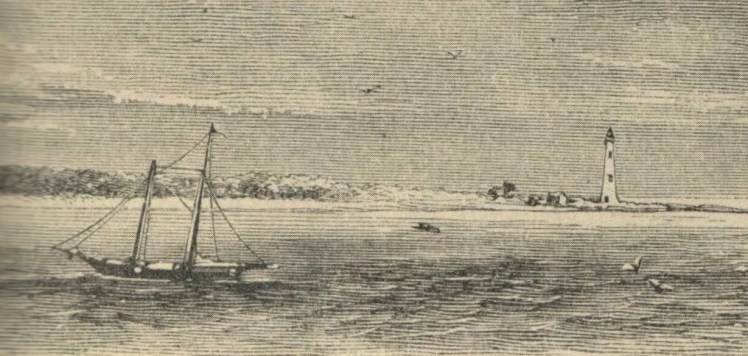

A shrieking gale and an angry sea, seemingly determined to drown Key Biscayne and everyone on it, drove John Dubose to seek safety in an upper story of the Cape Florida lighthouse. Unlike many seafarers who relied on its beacon for guidance, those dwelling on the Cape survived the September 1835 hurricane. Anything not secured to the ground, however, was swept away by the surging waters, which reached a height of four feet.

In the storm’s aftermath, Dubose took stock of what was left. His poultry had been carried off. The lighthouse boat had slipped its moorings and was found deposited on dry land. And the mulberry trees he’d planted showed no sign of life, “there being at that day not the least appearance of a bud.”1

In his tenth year as inaugural keeper of the lighthouse, the first built in Florida south of St. Augustine, John Dubose had figured since 1832 on the payroll of William A. Whitehead, who as customs collector at Key West had the oversight of this and three other lighthouses, and one lightship, strung along the 200-mile arc of the Florida Reef. The Cape Florida lightkeeper simultaneously served Whitehead as an inspector of the customs for the easternmost part of his district.

But Dubose answered to a different authority as well.

Henry Perrine, a New Jersey-born medical doctor turned horticulturist, had conceived a complex plan to colonize the south of Florida with tropical and exotic species. It was an idea to which he committed his worldly fortunes, and would one day sacrifice his life. From the diplomatic post he held at Campeche, Mexico, Perrine sent to Dubose and other experimenters dozens of plants and seed samples to test their viability in South Florida’s soil and near-tropical climate. Whitehead himself received, at the custom house on Key West, one of Perrine’s more unusual shipments. It consisted of cactus plants, hives of stingless bees from the Yucatán, and a pair of ill-starred rabbits: a questionable offering at best.2

Perrine didn’t limit his trials to species from a single continent. Hence the plantings on Key Biscayne, while small and experimental, included two kinds of mulberry tree: the paper mulberry (Morus papyrifera), which Dubose reported “grew finely” on the island and “became of some size,” and its near relative the fast-growing white mulberry, of the variety known as Morus multicaulis, original to Asia and introduced to the West (as Perrine believed) from the Philippines.3

While trees of the former type would perish in the floodwaters of 1835, the multicaulis within a month of their inundation sported an “abundance of well grown and ripe mulberries….” A score more of young multicaulis were introduced to the lighthouse gardens that fall, and two years later they were growing still.4

“These plants thrive well in this climate at all seasons,” Dubose found.

At the time I received them, I was unacquainted with their nature and value. … [O]ne planted in my garden on the main grew so rapidly, that I have often been obliged to cut all the limbs off, say six feet long; and as I did not know that they would grow, they were thrown away.5

Eventually he learned they could be easily propagated through cuttings. But a few months after the hurricane, Indian hostilities forced him to abandon his lighthouse duties and the mulberry nursery. Had he stayed, he believed he could, after two years, have boasted an orchard of 2,000 trees. Henry Perrine’s expectations were even more extravagant: “Had Mr. Dubose known the nature of the Manilla mulberry, or Morus multicaulis, and the best treatment of it in a tropical climate, he might now have multiplied these plants a million fold.”6

Of no less value to Perrine than Dubose’s reports of mulberry growth was the certainty that nothing like this had ever been attempted on the peninsula. After the lightkeeper’s inspection of supposed multicaulis plants at St. Augustine proved them to be specimens of the “Italian” mulberry instead, Perrine could confidently assert that he was “the person who first introduced the Morus multicaulis into East Florida….”7

Perrine’s pioneering experiments in Florida were aimed at nothing less than a revolution in American farming, but their aspirations were only incidentally commercial, extending well beyond the realm of agriculture or science. By cultivating non-native species in a landscape often seen as hostile to husbandry and even to human occupation, Perrine intended to break cotton’s grip on the Old South, staunch the exodus of a white “yeomanry” heading for better and cheaper land in the west, and reduce sectional strife by inoculating the country against “fanatical” abolitionist sentiment, or an insurgency or infiltration by “inferior” races.

Without touching on specifics or these more unsettling undercurrents in Perrine’s thought, Whitehead offered to the project what encouragement he could: “your undertaking, if successful, will eventually prove highly important to the interests of the Union,” he wrote. As a customs officer, however, he couldn’t help wondering how the crops Perrine wished to raise would compete with the same commodities imported from abroad, “most, if not all of the produce of the plants being free from duty….” Whether from an appreciation of its complexity, a grasp of Perrine’s physical fragility or a presentiment of his violent end, Whitehead thought it unlikely that the originator of this elaborate endeavor would benefit personally from any eventual success. As he said to Perrine, “I doubt if you will be the one to profit by that result.”8

But why, in this ambitious scheme, had Perrine assigned such primacy to Morus multicaulis? And what obliged John Dubose to assure him that no one in the Florida peninsula had raised this variety before?

Nature invested the tree with a peculiar appeal that made Perrine keenly interested in its cultivation. It was not for ornament that he wished to nurture it, nor for its sturdy and durable wood, nor even for its fruit. The value of the multicaulis, instead, was innate in its leaves, of which the “unappreciated climate of our southern Florida” virtually insured an unending supply. This attraction had been firmly impressed on Dubose who wrote, “One great advantage we will always have over our Northern friends, in the cultivation of the Morus multicaulis, is the fact that the tree does not cast its leaves through the winter, but is at all times in a situation to afford food for the silkworm.”9

Domestic silkworms, the larvae of the moth species Bombyx mori, have been bred for more than five millennia in China, where the leaves of the mulberry were found to be their favored food. After a month feeding on these leaves, the worms enclose themselves in cocoons, each consisting of a single filament of raw silk as long as 3,000 feet. The process of making silk for human use begins by meticulously unwinding, then combining the filaments from several cocoons to form a basic thread. This thread becomes the fundamental component of standard sewing thread, and innumerable fabrics and manufactured articles.

In their exploration and exploitation of other continents, Europeans could not but be enticed by the potential to enlarge and control the supply of this valuable commodity. When, in the early nineteenth century, the United States sought a measure of economic autonomy to match its lately-won political independence, the creation of a domestic silk culture was to have no shortage of adherents. Henry Perrine and his growers could be counted among these, if lacking the single-mindedness or luck needed to bring it to fruition.

Having heard and read Henry Perrine’s portrayals of Florida and its “more genial” climate as providing the best conditions for growing non-native species, William Whitehead may have been somewhat surprised, when he resettled in the North, to be met there with a frenzy for mulberry and silk cultivation. “The climate of every State in the Union is adapted to the culture of silk,” an 1830 Congressional report had pronounced, confident that enough of the material would soon be produced for export as well as domestic consumption.10

Even before that, the American Institute, whose yearly fairs in New York City gave public exposure to products of both factories and farms, had been awarding medals and commendations to local growers of cocoons and producers of fine silk. Many of these were farmers in Whitehead’s native state, including two who became prominent publicists for the industry: Jersey City’s Charles F. Durant, member of a loose circle of scientific men with whom Whitehead had been associated as a youth; and Monmouth County minister Donald V. McLean, a future collaborator (and sometime antagonist) of Whitehead’s in the enterprise that, in the 1840s, established the New Jersey Historical Society.11

By 1838, when Whitehead exchanged his Key West home for a new life in the urban North, the fervor for domestic silk culture, and the easily propagated multicaulis in particular, had reached unthinkable heights. State legislatures, including New Jersey’s, were prevailed upon to encourage the industry with financial incentives. New trees were under cultivation in prodigious numbers (a Newark newspaper estimated 320,000 “in the immediate vicinity of our city”), and seeds or cuttings of the valuable multicaulis were everywhere for sale. The Cheney brothers, experienced growers from Connecticut, set up a mulberry plantation and “cocoonery” at Burlington, New Jersey, and from there issued a monthly magazine, one of many such journals devoted to silk growing.12

The press carried occasional warnings about excessive speculation, exaggerated numbers of trees offered for sale, and even blatant fraud. But what brought the “mulberry mania” of the late 1830s to an end were a dearth of expertise and infrastructure, and a serious downturn in the economy overall. Not a few fortunes were wiped out when the bubble finally burst.13

If only because of his past acquaintance with Henry Perrine, Whitehead observed the national silk-growing frenzy with interest. But when he undertook to comment on it, he did so from an unusual vantage point. In searching for “historical matter” related to William Franklin, New Jersey’s last royal governor, Whitehead had found a precedent in the colonial records for legislative support of silk production. In 1839 the Newark Daily Advertiser, soon to become the repository of many historical articles from his pen, printed this finding, presented by its author, perhaps tongue in cheek, “as a contribution to the ‘Annals of Silk Culture’ in New Jersey.”14

The opening pages of those “annals” would have hardly seemed propitious. Although the mulberry tree was observed to flourish in parts of New Jersey, the assurances found in early descriptions that, “being store of Mulberrie-Trees, Silk-worms would do well there,” lacked the evidence of first-hand experience.15 Agriculture and manufacturing in New Jersey’s first centuries could make only modest progress, as British colonial policy tended to hinder their development except as components of a unified imperial system.

The stimulus to provincial New Jersey’s silk culture emanated chiefly from Governor Franklin’s famous father. Through two learned societies–the American Philosophical Society, which he co-founded in Philadelphia in 1743, and the London Society for Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, of which he was a corresponding member from 1756–Benjamin Franklin became the most visible, most ardent proponent of silk manufacture in the colonies. At his instigation, the Society for Arts (known today as the Royal Society of Arts) began to encourage silk production in America through privately funded bounties and premiums.16

Franklin’s son, who assumed the governorship of New Jersey in February 1763, was himself elected a corresponding member of the Society for Arts in the same month.17 Three years later, addressing the New Jersey Assembly convened at Burlington, where he would reside until 1774, the governor expressed the desire to see the inhabitants of the province “turning their Attention to the Cultivation and production of such Articles as might serve for Remittances to the Mother Country: and which, at the same time that they tended to her Advantage might prove beneficial to the Colony.”18

Franklin urged that the Assembly offer a bounty for growing hemp and flax to complement incentives already provided by Parliament, and referring to the “handsome premiums” awarded by the Society for Arts “for the Encouragement of the Culture of Silk, and the making of Wine and Potash in America,” he suggested the legislature likewise give encouragement to “the Production of those Valuable Articles.”

The Assembly, “with a View of stimulating our Inhabitants to future Industry and Wealth, in a Way hitherto but little used in this Government,” obligingly approved bounties for the raising of hemp and flax valid for two years and three months, and one for mulberry trees to last a full seven years, until 1772. The former bounties were later extended, so as to expire at the same time as that on mulberry trees.19

Franklin meanwhile had developed a deep personal interest in agriculture, entreating his father in London to forward details of the latest European discoveries and improvements in husbandry. “I have entered far into the Spirit of Farming,” he declared in 1769, having recently expanded the acreage he tilled outside Burlington, “on very reasonable Terms. It is now altogether a very valuable and pleasant Place.”20 While we don’t know whether the governor raised mulberry trees, it’s certain that others, many of them women, were growing them and raising cocoons for silk nearby.

In 1770, the Contributors for Promoting the Culture of Silk advertised the establishment of a “filature” for the unwinding of silk cocoons on Seventh Street in Philadelphia. The managers offered to pay for cocoons raised “in Pennsylvania, Jersies, Maryland, and lower counties of Delaware,” and award premiums to the most prolific producers.21 By its second year, the filature had provided ample demonstration of New Jersey’s skill at silk growing: a third of the cocoons it purchased came from the other side of the Delaware River, and two-fifths of its premiums were paid to Jersey farmers.22

In London, Benjamin Franklin was delighted to receive shipments from that and the next season’s crop. “I am charmed with the sight of such a quantity the second year,” he said, “and have great hopes the produce will now be established.”23 His son, however, had grown anxious. Perhaps out of a sense that it was meant primarily to “serve for Remittances to the Mother Country,” no one had ever applied for the bounty on raising mulberry trees. Supposing that New Jerseyans were just becoming “sensible of the Advantages which might accrue to them from the Culture of Silk,” the governor urged the renewal of that bounty, set to expire in October 1772. But the measure failed in committee, and the other incentives, originally adopted with it seven years earlier, were likewise allowed to expire.24

Burgeoning discontent with British policies, of course, had made a continuance of silk culture on the former terms less likely. And with “the dark clouds of the revolution” gathering above them, Assembly members became preoccupied by more urgent concerns. “From that time until late years,” Whitehead observed, “the subject was never brought to the attention of the Legislature so far as I can learn.” Colonial documents he gathered and studied in the years to come would confirm this impression.25

Despite the Revolution and the republican distrust of luxury products like silk as aristocratic trappings, despite the short-lived multicaulis craze and the “revulsion of public feeling” that followed, silk would want for true believers.26 Its manufacture was to have a rebirth, infamously in New Jersey, through an infusion of capital, mechanization and cheap immigrant labor. But the mulberry tree now serves as little more than an embellishment to New Jersey’s landscape, while the lowly silkworm toils thanklessly in regions more distant, surely, than Henry Perrine would have wished.

Copyright © 2025-2026 Gregory J. Guderian

Last revised 2026.01.14

[1] “Shipwrecks and supposed loss of lives. Effects of the late gale,” The enquirer (Key West, Fla.) 26 September 1835 3:(1-2)2; “Rapid vegetation in the southern part of Florida,” The enquirer 7 November 1835 2:3 (hereafter “‘Rapid vegetation’”). William A. Whitehead was then editor of the Key West Enquirer; for his treatment of the hurricane and its aftermath, see my earlier post 040–No enemy but winter and rough weather.

[2] See my earlier post 042–The collectors (part 2) for a profile of Henry Perrine and the fate of the items he sent to Key West.

[3] John Dubose, Key West 1 November 1837, to Henry Perrine, in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants. (To accompany bill H. R. No. 553.) H. Report No. 564, 25th Congress, 2d Session (hereafter “Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants”) 60. An initial shipment of a dozen multicaulis trees came to Dubose from New York, via Key West, in the spring of 1833. They were sent free of charge by Sylvie Parmentier, the widow of landscape architect André Parmentier. Henry Perrine, “Counter estimates, and objections to the alleged profits of mulberry culture. New obstacles to the tropical plant, scheme and operations,” The farmers’ register 7:6 (June 1839) (351-355, hereafter “Perrine, ‘Counter estimates’”) 353-354.

[4] “Rapid vegetation”; John Dubose, Key West 27 December 1837, to Henry Perrine, in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants 61.

[5] John Dubose, Key West 27 December 1837, to Henry Perrine, in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants 60-61. Jacob Housman likewise admitted to having cut off and unwittingly discarded the branches of two mulberry trees he planted on Indian Key in 1834: Henry Perrine, “Remarkable growth of morus multicaulis on a soil almost purely calcareous,” The farmers’ register 7:12 (December 1839) (764-765, hereafter “Perrine, ‘Remarkable growth’”) 764.

[6] John Dubose, Key West 27 December 1837, to Henry Perrine, with “Remarks by H. P.,” in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants 60-61. Perrine would elsewhere enlarge the number to “many millions”: Perrine, “Counter estimates” 354.

[7] John Dubose, Key West 27 December 1837, to Henry Perrine in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants 60.

[8] W. A. Whitehead, Key West 25 November 1837, to Henry Perrine, in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants (61-62) 62.

[9] Henry Perrine, Consulate U. S. A. at Campeachy 29 December 1834, Memorial to the Senate and House of Representatives (27-34) 34; John Dubose, Key West 27 December 1837, to Henry Perrine 61; both in Dr. Henry Perrine–Tropical plants.

[10] D’Homergue upon American silk. Report of the Committee on Agriculture on the growth and manufacutre of silk; to which is annexed, Essays on American silk, with directions to farmers for raising silk worms … H. Doc. 126, 21st Congress, 1st Session (Washington 1830) 6. A silk-growing manual published four years later shared this optimism: “Wherever the mulberry finds a congenial climate and soil, there also, the silk worm will flourish. Such a climate and soil, and such a country is ours, throughout its whole extent, from its eastern to its western shores.” William Kenrick, Silk, and the Chinese mulberry, or Morus multicaulis (Boston 1834) 4.

[11] See “Premiums of the American Institute,” The silk culturist, and farmer’s manual 2:9 (December 1836) 161; D. V. McLean, “Morus Multicaulis,” Monmouth County Democrat (Freehold, N.J.) 1 March 1838 3:1; “Debates in the silk convention,” Journal of the American Silk Society, and rural economist 1:1 (January 1839) (9-27) 17-20; “Rev. D. V. McLean’s experiment,” Journal of the American Silk Society, and rural economist1:11 (November 1839) 345-357; D. V. McLean, Freehold (N.J.) November 1839, to the Managers of the American Institute, and Charles F. Durant, Jersey City 13 November 1839, to the Corresponding Secretary of the American Institute, “Message from the Governor, on the subject of the culture of silk, and the manufacture of sugar from the beet root,” in: Documents of the Assembly of the State of New-York, Sixty-third session, 1840 (Albany 1840), Doc. 134 (12 February 1840) 9-18 and 19-30; “Address of Rev. D. V. McLean, of New Jersey, before the American Silk Society, in the Hall of the House of Representatives, at Washington, Thursday evening, Dec. 12, 1839,” Journal of the American Silk Society, and rural economist 1:12 (December 1839) 377-391 and cf. 399-400. Also see notices in Newark daily advertiser 18 October 1838 2:4, 9 October 1839 2:4, 19 December 1839 2:2, 21 December 1839 2:5; New-York (N.Y.) commercial advertiser 13 November 1839 1:7. For McLean’s role in the Historical Society’s creation and the controversy over the location of its library, see my earlier posts 049–Try, try again and 082–A house divided. For Whitehead’s association with the scientific circle that included Charles F. Durant, see 033–Fathers of invention, 090–Ascension, and 104–Foreign affairs. If Durant enjoyed the admiration of Henry Perrine for having “always preached and published the only true doctrine” of silk culture, his assertions were roundly criticized by other cultivators: “A letter by Dr. Henry Perrine,” Tequesta: the journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida 39 (1979) (29-33) 30; G. B. S., “Mr. Durant on the culture and commerce of silk,” Journal of the American Silk Society, and rural economist 2:2 (February 1840) 63; Layton Y. Atkins, “Durant on silk,” Journal of the American Silk Society, and rural economist 2:3 (March 1840) 68-73; cf. Elizabeth Howe, “A forgotten naturalist,” The lamp. A review and record of current literature 28 (1904) (485-487) 486.

[12] See “American manufacturers. The silk business,” Newark (N.J.) daily advertiser 17 July 1837 2:1; cf. “Silk culture and mulberry speculation,” The farmers’ register 6:7 (July 1838) 425-426. Government support for silk production became, unsurprisingly, a political football in New Jersey: see Newark daily advertiser 4 February 1839 2:2, 25 February 1839 2:1. Ward Cheney’s American silk grower and farmer’s manual was published at Burlington from July 1838 through December 1839, before being absorbed by Baltimore silk pioneer Gideon B. Smith’s Journal of the American Silk Society, and rural economist. For a sample of periodical titles devoted to sericulture, see Ben Marsh, “The Republic’s new clothes: making silk in the antebellum United States,” Agricultural history 86:4 (Fall 2012) (206-234) 230 note 9. The trials and triumphs of early American silk culture were surveyed in two late nineteenth-century works: L. P. Brockett, The silk industry in America. A history: prepared for the Centennial Exposition (New York 1876), and Wm. C. Wyckoff, American silk manufacture (New York 1887).

[13] An admonition against believing inflated claims was addressed to readers of the Newark daily advertiser 27 December 1838 2:4. Henry Perrine realized, perhaps too late, that the predominantly Northern mania for multicaulis would derail its cultivation in South Florida: “The greatest natural importance of the propagation of the mulberry trees consists in the fact that they are naturally adapted to propagate themselves in the poorest soil; and hence their value is infinitely diminished by the artificial process of forcing their multiplication for trading speculation.” Henry Perrine, Indian Key (Fla.) 1 January 1839, to the Editor, in “Progress of Dr. Perrine’s scheme of introducing tropical plants. Letter of Chief Justice Marshall,” The farmers’ register 7:1 (January 1839) (40-41) 41.

[14] G. P., “Silk,” Newark daily advertiser 23 February 1839 2:3. Previously, Whitehead had published in the same paper and signed with the same cryptic pseudonym a series of fifteen “Letters from Havana.” They ran from 31 July through 26 September 1838.

[15] “There is no appearance here of salt, or of silkworms,” Governor John Printz reported from the Swedish colony on the Delaware River, “because the winter is sometimes so sharp, that I have never felt it more severe in the northern parts of Sweden.” Gregory B. Keen, trans. “The report of Governor Johan Printz, of New Sweden, for 1647, and the reply of County Axel Oxenstjerna, Chancellor of Sweden,” The Pennsylvania magazine of history and biography 7:3 (1883) (271-285) 272. A century later, his countryman Pehr Kalm observed an abundance of red mulberry trees, growing both wild and “in yards … carefully planted,” but made no mention of silkworms. Esther Louise Larsen, “Pehr Kalm’s description of the North American mulberry tree,” Agricultural history 24:4 (1950) (221-227) 221-222. Dutch, English and Scottish writers all promoted the region’s potential for raising silkworms and producing silk: see David Pietersz. de Vries, Korte historiael, ende journaels aenteyckeninge, van verscheyden voyagiens in de vier deelen des wereldts-ronde, als Europa, Africa, Asia, ende Amerika gedaen (Hoorn 1655) 169; An abstract, or abbreviation of some few of the many (later and former) testimonys from the inhabitants of New-Jersey, and other eminent persons, who have wrote particularly concerning that place (London 1681) 7 (whence the quotation above); A brief account of the Province of East-New-Jarsey in America: published by the Scots Proprietors having interest there. For the information of such, as may have a desire to transport themselves, or their families thither… (Edinburgh 1683) 11; [George Scot,] The model of the government of the Province of East-New-Jersey in America: and encouragements for such as designs to be concerned there. Published for information of such as are desirous to be interested in that place (Edinburgh 1685) 69-70, reprinted in William A. Whitehead, East Jersey under the Proprietary governments: a narrative of events connected with the settlement and progress of the province, until the surrender of the government to the Crown in 1702 [1703] (Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1) ([New York] 18461) 266, (Newark 18752) 396.

[16] For Franklin’s support of silk culture as a member of the Society for Arts while resident in London, see D. G. C. Allan, “‘Dear and serviceable to each other’: Benjamin Franklin and the Royal Society of Arts,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 144:3 (September 2000) 245-266, esp. 252-254. The records of the Society from its founding in 1754 to 1776 showed that £1,665 were awarded in premiums for “planting Vines and Mulberry Trees, and producing Silk,” yielding 11,575 pounds of raw silk from North America. A register of the premiums and bounties given by the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, from the original institution in the year MDCCLIV to the year MDCCLXXVI inclusive (London 1778) 19. For the American Philosophical Society’s encouragement of silk production see Brooke Hindle, The pursuit of science in Revolutionary America 1735-1789 (Chapel Hill, N.C. 1956) 199-202.

[17] A membership list of 1 August 1777 names “Franklin, William, Esq., of the Jerseys.” By then he had been taken prisoner and removed to Connecticut. D. G. C. Allan, “Studies in the Society’s history and archives CLXIV. ‘The present unhappy disputes’: the Society and the loss of the American colonies, 1774-1783,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 130:5307 (February 1982) (156-161) 160 and cf. 159.

[18] Speech of Gov. William Franklin to the Council and Assembly, 22 May 1765, in Frederick W. Ricord, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 17. Journal of the Governor and Council, 5. 1756-1768 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 17. Trenton 1892. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 17”) (384-387) 385-386.

[19] Address of the General Assembly to Gov. William Franklin, 15 June 1765, in William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 24. Extracts from American newspapers, relating to New Jersey, 5. 1762-1765 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 24. Paterson 1902. Hereafter “NJA ser. 1, 24”) (554-556) 555; Acts of the General Assembly of the Province of New-Jersey … (Burlington 1776) 281, 313; NJA ser. 1, 17:498. Cf. William Franklin, Burlington 8 August 1765, to the Lords of Trade, in Frederick W. Ricord and Wm. Nelson, edd. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 9. Administrations of President John Reading, Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Pownall, Governor Francis Bernard, Governor Thomas Boone, Governor Josiah Hardy, and part of the administration of Governor William Franklin. 1757-1767 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 9. Newark 1885) 490-491.

[20] William Franklin, Burlington 11 May 1769, to Benjamin Franklin, in [William Duane, ed.] Letters to Benjamin Franklin, from his family and friends. 1751-1790 (New York 1859) (41-45) 42; cf. “Three letters from William Franklin, Governor of New Jersey, to his father, Dr. Franklin, copies of which were presented by William Duane, Esq., of Philadelphia,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society [ser. 1] 1:3 (1845-1846) (102-109) 106-107; William B. Willcox, ed. The papers of Benjamin Franklin 16 (New Haven and London 1972) 126-130, and ibid. 61.

[21] William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 27. Extracts from American newspapers relating to New Jersey, 8. 1770-1771 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 27. Paterson 1905; hereafter NJA ser. 1, 27) 176-177.

[22] As proof that “the Culture of Silk is a Matter of great Consequence to the Interest of this Colony,” the New Jersey Assembly’s printed minutes for 18 December 1771 included a report from the Philadelphia filature. See Votes and proceedings of the General Assembly of the Colony of New-Jersey. At a session of general assembly, began at Burlington, Wednesday the 17th of April 1771, and continued by Adjournments and Prorogations, until the 21st Day of December following. Being the third sitting of the fourth session of the 21st Assembly of New-Jersey (Burlington 1771) 63 et seqq. More than half the Jersey growers named in the report were women, of whom at least one, Sarah Bispham of Burlington County, was due a prize for her success in raising cocoons: NJA ser. 1, 27:588.

[23] Benjamin Franklin, London 6 February 1772, to Cadwallader Evans, in Jared Sparks, The works of Benjamin Franklin; containing several political and historical tracts not included in any former edition, and many letters official and private not hitherto published; with notes and a life of the author (rev. edn. Philadelphia 1840) 8:(3-4) 4.

[24] Votes and proceedings of the General Assembly of the Colony of New-Jersey. At a session began at Perth-Amboy, Wednesday, August 19th 1772, and continued until the 26th day of September following. Being the first session of the twenty-second Assembly of New-Jersey (Burlington 1772) 5, 10, 18-19; Frederick W. Ricord, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 18. Journal of the Governor and Council, 6. 1769-1775 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 18. Trenton 1893) 299; William Nelson, ed. Documents relating to the colonial history of the State of New Jersey, 28. Extracts from American newspapers, relating to New Jersey, 9. 1772-1773 (Archives of the State of New Jersey, ser. 1, 28. Paterson 1916) 223, 225-226.

[25] In 1778, the New Jersey legislature approved a bounty on wool, flax and hemp raised within the state. It was limited to two years, and did not include silk. Peter Wilson, comp. Acts of the Council and General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey, from the establishment of the present government, and Declaration of Independence, to the end of the first sitting of the eighth session, on the 24th day of December, 1783 … (Trenton 1784) 42.

[26] While the multicaulis fever subsided, the belief persisted “that New Jersey may become a great silk growing community,” and that the “merits” of the enterprise were “in danger of being as much underrated as they may have been overestimated.” Newark daily advertiser 23 December 1839 2:1.